Alexander Zemlianichenko, Yeltsin In Rostov, 1997 Via IANN

I am sitting with two of my oldest family friends in a pleasant Georgian restaurant in Moscow. It is early August, 2011. The food, like the neighborhood—everything around here is named after Ukraine—is one of those latent reminders of empire that continue to go completely unremarked in Russia, regardless of geopolitical vicissitudes. It is so delicious that we gorge ourselves on appetizers and give up on entrées completely. After three glasses of wine (for me, a decent dry red, something that less than a decade ago would have been a remarkable find in a place like this) conversation flows briskly, and the usual topics—life in the States, dating, vacations, food—are quickly exhausted. I sit quietly for a bit and, eventually, manage to ask: so, the anniversary of the August 1991 putsch is this month, are you celebrating?

My friends, S and his wife T, like my father and mother, are in their mid-40s, meaning they were all graduating from Moscow University together in the heady perestroika climate of the late 1980s (of which my generation of Russian twentysomethings sometimes seems the only tangible reminder). S was even a Soviet hippie; he rode the rails according to a schedule, known as “The System,” that enabled properly-equipped flower children to avoid conductors and travel from city to city essentially for free. He likes to tell stories about smoking bad pot with the members of a niche—though, like all of them, semi-legendary—Soviet art-rock band. But their whole generation was vaguely countercultural in those days. My father had a Communist Youth League-issued Soviet flag that he kept around expressly for the purpose of using it as a tablecloth; his friend owned a bust of Lenin to which he would offer sacrifices before major exams and which he would beat on the head if the results were unsatisfactory; my mother’s ex-husband demonstratively flushed his election ballots down the toilet. I learned that this was not just a fluke when I watched Robin Hessman’s documentary My Perestroika a few months earlier and saw a procession of the same types of people telling the same stories. My parents’ generation were almost the Baby Boomers of their time.

I tell you this because I want to underscore how unexpected it was to hear—instead of a half hour or so of complacent Boomer-style reminiscence about how bliss it was in that dawn to be alive, but to be young was very heaven, and so forth—only a couple of seconds of embarrassed silence. Then T cleared her throat and said, “Well, you see, for us what August 1991 meant was the beginning of the ‘90s. Things were really very tough. We don’t see it as something to celebrate.” “But it was the end of the Soviet Union!” I protested, “People in the streets! Don’t you think it’s a big deal?” S chimed in: “I remember when I heard there were people protesting in the streets. I went to take a look. It was bullshit. No one knew what they were doing there. They were just hanging out and drinking. I saw two drunken assholes fighting over a bottle of vodka. That’s all it was. Drunken assholes fighting.”

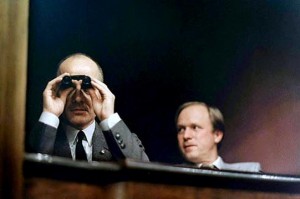

This, in fact, was not an inaccurate summary of the high politics either. On August 19, 1991, several leading, mildly-to-strongly hardline members of the state and Communist Party apparatus tried to seize power by locking up Gorbachev in his dacha, moving tanks into the capital, and forming a “State Emergency Situation Committee.” When they held a press conference—now visible in its unimpressive entirety on YouTube—it was clear that they were not up to the task: the country saw on its television screens the bleary, bored, and visibly drunk faces of two generations of apparat inbreeding. After street protests in which the army refused to cooperate with the putschists, Boris Yeltsin, already known for the alcoholism that would soon make him a global laughingstock, swooped in and definitively established the sovereignty of Russia (or rather, the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic) vis-à-vis the Soviet Union by changing the national flag. By August 23, he had disbanded the Communist Party of the RSFSR—an act approximately comparable to Joe Biden announcing the immediate nationalization of the assets of every American corporation worth over $1 billion. (The presidential decree cheekily pointed out that the Party was “not registered in accordance with established procedures.”)

The history seems straightforward. It doesn’t seem substantially different from the triumphs of this year’s Arab Spring. In that light, the reactions of my friends seem bizarre and inexplicable. But they aren’t alone. A poll released this month to coincide with the anniversary of the coup reveals that only 10% of Russians consider the defeat of the putschists a victory for democracy, while 39% think of it as a “tragic event with ruinous consequences for the country and its people.” In order to figure out what this statement means, it’s necessary to understand the meaning of “the 1990s,” as a general term, for Russians today.

When post-Soviet Russia emerged blinking into the light, it very quickly became clear that it was not the protesters in the street, or even the drunken assholes in the government, who were calling the shots in the new regime. Instead, it was a whole crew of people long ready for a transition to capitalism: not just the factory directors who rushed to privatize and incorporate their giant, often city-sized fiefdoms, but also hotshots from the Communist Youth League, “cooperators” who had begun to pursue private enterprise under the auspices of Gorbachev’s perestroika, and a host of others who had their fingers on just enough power and capital to position themselves for a running start after the Soviet collapse. The rigged auctions by which state property was handed out to these entrepreneurs would soon become Exhibit A for accusations that Yeltsin’s government was hopelessly corrupt or incompetent or both. Meanwhile, in a hack scheme, regular people could obtain “privatization vouchers,” redeemable for shares in newly-privatized state enterprises. In practice, the vouchers soon devalued rapidly, and the hordes of investment funds set up to repurchase them from the population—even the few that were not based on fraud—rarely produced any benefit to their small shareholders. The wealth that, in the Soviet Union, had been controlled by the State and the Party was now controlled by an even smaller circle of oligarchs with considerably less regard for legal niceties.

The authority of the government was collapsing too. Subsequently, the Yeltsin cabinet defended itself with the claim that there was nothing it could do—its only option was to give a stamp of legality to the widespread looting happening all across the country and thereby to preserve at least some nominal claim to authority. (Actually, this is probably the most plausible explanation—conspiratorial accounts of “shock therapy” continue to proliferate, but they are both less elegant and less believable.) Propped up by massive IMF loans whose funds mostly vanished mysteriously soon after they arrived, the country fell into catastrophic debt. Harvard Business School experts swooped in to reap massive salaries advising the politicians on how to create an “economic miracle” along neoliberal lines. This particular disaster was especially galling, administered as it was by Russia’s former Cold War adversary. A war begun in an attempt to prevent the tiny republic of Chechnya from seceding ended in an ignominious and humiliating defeat. Predictably enough, nationalist and (bizarrely, given the country’s obsession with its victory in World War II) neo-Nazi groups sprung up, like mushrooms after the rain.

Daily life was no more encouraging. Stores were empty. The quiet residential streets of major cities regularly became staging grounds for firefights between organized-crime groups. (Among the most durable legacies of this period are the steel doors that still protect half of Moscow’s apartments.) In the absence of a functioning public or private sector, unemployment soared. Millions lost their savings in high-profile pyramid schemes that seemed to offer their victims an opportunity to become winners in the post-Soviet game—that is, if they hadn’t already lost them to hyperinflation, which hit 2,600% at the end of 1992 and continued rising for several more years.

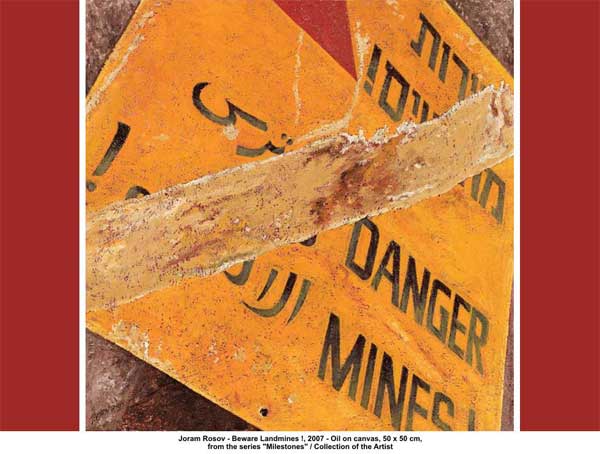

I don’t want to belabor the point. A complete accounting of all the woes that accompanied the collapse during that decade would take a book, which, fortunately, has already been written several times over. (The best is probably Stephen Kotkin’s Armageddon Averted.) I cite these circumstances only in order to make clear what August 1991 brought into being: the 1990s as a fact, yes, but also the 1990s as a national myth. The credible claim to have brought the country out of the 1990s and into the realm of “stability” is the ideological centerpiece of the political configuration associated with Vladimir Putin.

In a 2005 letter to the Federation Council—Russia’s upper legislative house—Putin made the claim, subsequently cited over and over again in the Western press, that “the fall of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” To a non-Russian ear, this sounds very close to an argument for the restoration of the USSR: “fall,” on this reading, is an attribute of “Soviet Union.” In context, however, it’s clear that what he is talking about is not “the fall of the Soviet Union,” but “the fall of the Soviet Union”—or “the collapse,” for short. Here’s the original passage:

Above all it is necessary to acknowledge that the fall of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century. For the Russian people it became a real tragedy. Tens of millions of our countrymen and fellow citizens found themselves outside Russian territory. The epidemic of collapse also spread to Russia itself.

Citizens’ savings became worthless, old ideals were destroyed, many institutions were disbanded or hastily reformed. The country’s integrity was violated by terrorist intervention and the subsequent Khasavurt capitulation [in the First Chechnya War]. Oligarchical gangs, possessing unlimited control over information streams, served only their own corporate interests. Mass poverty began to be seen as a norm. And all this happened against a background of severe economic collapse, financial instability, and the paralysis of the social sphere.

It is against this background that Putin stakes his claim to authority as the leader of a resurgent Russia.

So why does the American commentariat insist on reading the Putinist rejection of the 1990s as a rejection of liberal democracy and a defense of authoritarianism? To be sure, “stability” has meant a dramatic retrenchment in the freedom of speech and of the press (though never quite as dramatic as it is often depicted), and Putin postures as a post-Stalinist strongman at every opportunity. But it is odd to see these fairly contingent features of Putinism depicted as fundamental. In fact, the American view of Putin relies on something else brought into being by August 1991: the American myth of the Russian ‘90s as a period of liberal-democratic flourishing and triumph. It is on full view, for example, in Leon Aron’s heart-stoppingly moronic recent piece in Foreign Policy.

Vladmir Putin, via Funny or Die

It is important that this myth did not, in fact, take hold until well into Putin’s presidency. Yeltsin, who resolved a full-scale tanks-and-corpses political crisis in 1993 by asserting unilateral executive authority and who was widely viewed as plotting to revise the constitution in order to stay in power indefinitely, certainly provoked his share of anxious clucking from State Department officials. The chaos and economic collapse in Russia was no secret for the Western media. In 1999, the Onion even ran an article headlined “Russian Television Scores Hit With New Game Show Who Wants To Eat A Meal?” Somehow, over the course of the 2000s, the authorized American narrative of post-Soviet history metamorphosed from a woe-filled tale of misery and social breakdown to a nostalgic reminiscence about a lost pre-Putinite golden age of pluralism.

The nostalgia has clear sources. American news- and opinion-makers who experienced Russia in the 1990s now occupy senior positions that allow them to define the conventional wisdom on the subject. They did not live through anything like the experience of the average Russian or even the average Muscovite of the time. In other words, they are nostalgic not so much for a real decade as for their dreamlike experience of that decade, when they occupied the most enviable and lucrative positions at the heart of the post-collapse vortex of money and power.

They were in Moscow effectively as—not to put too fine a point on it—post-imperial colonialists. Take, for instance, the self-description of the Facebook group “Moscow in the ‘90s,” composed of a substantial number of middle-aged people with Anglo-Saxon last names:

A group for all who were in Moscow in the glorious 1990s. The last days of the Soviet Union, the first of the CIS; Yeltsin, Gaidar, Chernomyrdin and Zhirinovsky; The Moscow Times, The Moscow Tribune, The Exile; Aug ’91 Putch, Oct ’93 White House siege, Chechnya; Mercenary Photos, Petlura’s Place, InterFoto; The Hungry Duck, News Bar, Night Flight, Krisis Zhanra; MMM, PrevitiZAtsya…

There are three things to notice about this paragraph, aside from the badly transliterated “privatization” at the end. The first, of course is the word “glorious.” The second is the list of bars, which all happened to be famous expat bars whose entire reason for existing was the provision of alcohol and prostitutes to moneyed Westerners come to cash in on the IMF largesse. Finally, there is the list of newspapers—the English-language press in which the expat community talked endlessly to itself.

The eXile, last on that list, is the most important of all of them. When it was finally shut down by the federal communications bureau in 2008, nearly every journalist of significance to have been posted in Moscow during its lifetime crawled out of the woodwork to pronounce an encomium: no one really approved of The eXile, but everyone read it. The eXile was both the expat culture’s freakish funhouse-mirror reflection and its most extreme manifestation.

Started in 1997 by a band of punky American expats (Matt Taibbi, among them) together with Eduard Limonov, a perenially non-grata writer and political activist, The eXile both raged against expat culture and celebrated its capacity for orgiastic excess. On the one hand, The eXile’s writers mounted a relentless attack on the smugness of American expats and their journalists in particular; in one memorable incident in March 2001, Taibbi threw a pie full of horse sperm in the face of the New York Times’ Russia correspondent Michael Wines, accompanied with vivid rhetoric denouncing his whitewashing of American imperialism. (The article incisively observes, in passing, that Putin was initially supposed to be a right-wing market-friendly strongman along the lines of Pinochet, which is why he did not become a foreign-relations villain for the Americans until somewhat later.)

Yet the very same issue featured a piece by Mark Ames called “Snapper Season,” containing the memorable line “One unavoidable consequence of the upcoming Snapper Season is that your Russian girlfriend will now become as unreliable and disobedient as your dog Rex was every May.” This was characteristic of The eXile: even as it denounced the political assumptions of ‘90s expat culture, it embraced the expat lifestyle wholeheartedly. Moscow was one big nightlife spot filled with endless cheap booze and drugs and endlessly available, undifferentiated, willing female flesh, whether obtainable directly through prostitution or in the fictive guise of a relationship. As a result, The eXile enjoyed tremendous popularity among expats: they could skip the political bits and go straight to the nightclub reviews, an area in which its reputation was unequalled. The risqué first-person stories of coke orgies and casual whoring only served to enhance the general impression. In short, The eXile and the rest of the expat ecosystem helped convince the well-heeled international banker or bureaucrat that Cold-War-loser Russia was a place of unbridled license where everything could be had for a few bucks and without consequences.

Small wonder that the Putinist turn toward “stability,” “sovereign democracy,” and poorly-articulated pseudo-nationalism sounded to them like the death knell of ‘90s freedoms. If nothing else, Putin made sure that members of an emerging, apolitical native elite got first dibs on the petrodollars the country was now cranking out. Foreigners no longer inspire in Russians anything like the kind of instinctive embarrassment and reflexive kowtowing they did fifteen years ago. Moscow is more expensive now than almost every other city in the world. These are symptoms of a kind of stability successfully established—the ‘90s ended around 2002—and they have been in place long enough that they do not seem controversial. In fact, it is already beginning to seem as if the myth of that lost decade no longer automatically inspires devotion to the current leadership.

The result is an interminable dog-and-pony show in which the Kremlin is casting about for even a mildly compelling new ideology, with Putin and Medvedev as the puppet-show alternatives representing exhausted pseudo-populism and comically eggheady liberal-democratic jargoneering respectively. The collapse, for its part, has retreated completely into the shadows. Putin seems to sense that beating the ‘90s drum no longer works to rile up the masses; that’s understandable enough. It is somewhat stranger that Medvedev does not appeal to the liberal politics that did exist during that decade—but still not that strange. The fall of the Soviet Union, despite its irreversibility, is a totally ruined brand.

]]>

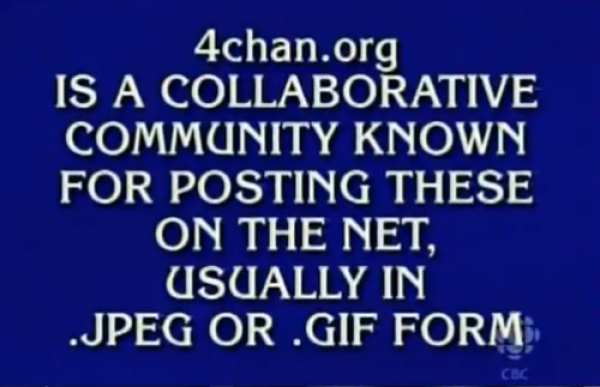

via geekosystem

Intellectuals today are, as usual, in a state of crisis. Nobody wants them in Washington; nobody wants them for a revolutionary vanguard; nobody wants them as benevolent cultural arbiters. Even the humanities departments that form their most reliable refuge are under perpetual threat of budgetary annihilation and bureaucratic meddling. Worse yet, many of their problems are traceable to the cultural reverberations of new technologies—the very sphere in which they should be ahead of the crowd. The reading and writing practices that have evolved on the Internet give less and less recognition to the esoteric scribblings of the scholarly virtuoso. For-profit colleges, with their long-distance classrooms, have little time for bell hooks and Bourdieu. E-books are hard to show off on a shelf.

This litany of tribulations is capped off by one central problem: the electronic cultural landscape of the early 21st century is a uniquely dispiriting place for intellectuals. This new world makes it difficult or impossible for them to flex their muscles as critics or to draw on the theoretical legacies that have fueled their conversations for decades. Internet-inflected resuscitations of Marx, Debord, and the Frankfurt School fail again and again to gain purchase on the field of activity they are supposed to explain. After all, the field is dominated not by struggling subjects or political mystifications, but corporations and their enthusiastic consumers. The discovery that the capitalist world is a show or a simulacrum has, in this context, lost all its pathos. It’s hard to find a victim in all this gleeful celebration of marketing. The cranky-cultural-critic pose of an Adorno has proven to be a refuge for many intellectuals who have confronted this dilemma, but it is not sustainable for long: moralism has, almost by definition, a limited shelf life, and it is especially difficult to keep up when one is increasingly obligated to maintain a lively presence in the spaces administered by Facebook and Google. “When the service is free, you are the product” may end up being one of the most significant maxims of our time.

While corporate dot-coms like Twitter and the Gawker network have been responsible for many of the loudest Internet phenomena of recent Internet history, there is one site that has outdone all of them: 4chan. Founded in 2003 by then-15 year old Christopher Poole (known everywhere as “moot”), it was originally an imitation of a Japanese anime forum, but has since transformed into something much larger and more anarchic. Naturally, 4chan has not only not gone public, it has apparently resisted any attempt to make it into a business at all (although it does support an enormous ecosystem of sites that do everything from archiving its contents to selling Japanese sex toys to its nerdy teenage audience). The site’s userbase is almost entirely anonymous—but for its IP addresses, which 4chan’s founder admitted to keeping at a Congressional hearing—and constantly shifting. Threads, by site policy, are deleted permanently after a few minutes of inactivity; this means the site has no official archive or memory, unlike the rest of the Internet, which usually retains data forever. The place is moderated, but the admins restrict themselves to removing child porn and overt terrorist threats rather than, as with most other sites, hate speech and other outré comments. The result is a massive cesspool that has come to epitomize the electronic id.

via indebraendt.dk

Naturally, 4chan would hardly be noteworthy if it were not also an enormous engine of creativity. In fact, it has gradually become enthroned, in media discourse as well as popular legend, as the fount and arbiter of everything that is unique to Internet culture. (The moment when Rick Astley burst out of a float at the 2008 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade may be considered a watershed in this process.) Even memes that actually originated elsewhere, like LOLcats, have popularly been ascribed to 4chan, not least in the collective memory of 4chan itself.

For intellectuals, then, the site is a real goldmine. Because it seems to be the true inheritor of the anarchic, populist, anticommercial promise of the Internet, the site can potentially be the hero of a triumphant narrative about organic culture-formation, anti-corporate resistance, and decentralized political action. It helps that 4chan—or “Anonymous,” the moniker its users employ when they engage in mass actions—is fully conscious of this aspect of its power, and uses it to stage actions ranging from the vaguely dadaist (the successful and technologically-sophisticated attempt to hijack the Time 100 poll in 2009) to the explicitly anti-authoritarian (its global, masked protests against the Church of Scientology in 2008). An observer looking to catch the leading edge of the future of activism could hardly be faulted for seeing it here.

And then there’s the dark side. The site’s aesthetic befits its uncontrolled nature. It is unapologetically racist, sexist, and homophobic; its angsty, geeky, and juvenile constituency seems to wear its emotional immaturity as a badge of pride. It’s as if the whole culture of 4chan were designed deliberately to upset liberal academics. Yet the slight frisson of the taboo that one gets while reading it (a hard feeling to avoid even for the most jaded Internet consumers) could be taken by intellectuals, not as grounds for condemnation, but as the ultimate proof of its authenticity. Unlike the comfortable, inoffensive activism on Twitter, which failed so resoundingly to produce change in Iran, 4chan gets things done—even if its merciless vigilante methods ruffle some feathers.

But are all these hopes justifiable? Can we really defend the idea that 4chan represents a new type of anything, much less political activism? There are good reasons to be skeptical. To begin with, the site’s edgy façade is to a large extent a simple put-on. Yes, posters call each other “fags” and throw around “nigger” like it’s 1850—but when questions about gay marriage and economics are put to them directly, they turn out to be a fairly unremarkable cross-section of American society. Gays, women, and black people appear to be represented proportionately, which is what leads to occasional bickering between “gayfags” and “straightfags.” Most importantly, nearly everyone there is young. As other popular websites have begun to approximate the demographic curve of the general population, 4chan has stayed young (although different boards vary in this regard; /b/, the loudest representative of 4chan in the wider world, is associated with high-schoolers, while /r9k/ is home mainly to self-pitying twentysomethings).

Anons, in other words, are not mysterious Hollywood über-hackers able to command computer networks at the touch of a key. In fact, their best-known pranks eschew technical expertise in favor of sheer numbers: the Time prank, though clever, needed only a simple program and a set of rules to be distributed to a horde of twitchy-fingered voters. And, like any movement that relies on the involvement of masses of willing participants, most of their campaigns fail to gather enough steam to make it onto the daily news. The internet harassment and vigilantism Anonymous is best-known for requires only a sufficient degree of malice and mutual encouragement to make an impression. 4chan’s numbers are not simply a major component of its success—together with its amorality (or rather its selective and idiosyncratic brand of morality), they are its central resource.

As for 4chan’s fertility as a source of memes, that, too, is a function of numbers, but the relationship between numbers and success is far from clear-cut. The site is constantly rocked by squabbles over whether it can maintain the originality that made it famous. The central charge is that “newfags” have brought “cancer” in the form of derivative and lazy meme-generating practices; the debate over who qualifies as a “newfag” and what as “cancer” gets predictably bizarre, given that the length of an anon’s tenure on the site can never be determined or substantiated. Looking at the site’s day-to-day activity, it is difficult to tell whether its creative energy really lies in its massive and anarchic structure. Occasional flashes of brilliance are buried and drowned just as quickly as the dreck.

via motivateurself

4chan will not save Internet culture from corporatization, even if it wants to do so. Nor will any of the other analogous sites (like the SomethingAwful.com forums, which have existed even longer). But that does not mean it is not a successful phenomenon in its own right, and one with considerable interest to intellectuals. In order to get at what makes it interesting, however, we should put aside any assumptions about its potentially anti-commercial implications. “4chan culture,” if we can call it that, works together with the world of Google and Facebook, not against it.

In particular, 4chan’s success is due not to its anarchic features, but its ability to institutionalize them. Internet culture is characterized by the fluidity of the boundaries between creative consumption and production. By relying on plagiarism, appropriation, and the exploitation of all available Internet resources, 4chan turns the basic habits of Internet consumption—sharing, voting, and other low-investment activities—into tools for productive activity that takes place under the banner of a common creative project. (Admittedly, “creative” can include ordering thousands of pizza deliveries to the house of an unsuspecting victim.) The corporate-driven social networks depend on this kind of production to sustain them, but they have so far failed to produce anything coherent themselves. The network that first learns how to learn from 4chan will likely change the face of the Internet permanently, and there are signs that sites like reddit have already moved in this direction.

In short, 4chan is likely to end up not as the harbinger of a more bottom-up, decentralized Internet but as a testing ground for its further commercialization. This should not be surprising. Like most emerging technologies, the Internet has followed the Leninist blueprint by rapidly transforming from a bazaar dominated by fringe hobbyists and grassroots activists into a controlled marketplace organized around crucial monopolies. This does not mean that the hobbyists and activists have disappeared—quite the opposite, in fact—but rather that they must increasingly operate under the umbrella of corporate networks. Corporations have never been entirely absent from the Internet, even in the 1970s, but its future history will be written more and more about them.

via the demotivators

The only way intellectuals can hope to deal with this apparently dystopian future is by accepting it. It remains to be seen whether critique in the Frankfurt School sense can survive such a gesture, but if it is to be viable at all, it can no longer oppose itself to capitalism or the corporatized world without becoming even more irrelevant. What will be left will be a kind of marine biology, the contemplation of the lifecycle of giant corporate squid as they struggle and envelop each other, each tentacle crowded with helpless symbiotes. 4chan is as unlikely to survive in its present form as any coral reef in the oceans of 2050—but its millions of tiny skeletons will have reshaped the Internet landscape for good.

]]>

via Drugoi

This summer, Russia was in flames. A record-breaking heatwave swept over the temperate zone, turning everyone from “office plankton” to government officials into slaves of the few available air conditioners. (Moscow, like most northern cities, is singularly ill-adapted for hot weather.) Then it got worse: fires began in the peat bogs ringing the city, engulfing it in opaque, toxic smog. The heat and the accompanying drought destroyed the grain harvest in much of the country, leading to a freeze on grain exports and a potential agricultural crisis. Finally, the massive forests of central Russia caught fire, destroying military facilities and private homes alike. As I write this, the massively overstressed bureaucracy charged with mitigating the consequences of emergencies is still trying to do its job, though it is failing visibly. The result, predictably enough, is popular discontent and political scandal.

Of course, blame is directed at the usual suspects: Prime Minister Putin, President Medvedev, and the party apparatus that is supposed to be the foundation of their power. Everyone’s a critic; whether it’s the recently-passed new law on forest management, which was supposed to devolve fire-protection functions to local government and private organizations, or the bureaucratic opacity and infighting that allegedly prevents accurate information from being distributed and acted upon, or the publicity stunts that the country’s leaders appear to prefer over effective action, ultimate responsibility seems always to come from the top.

For most Western observers, and for the handful of perennially threatened liberals inside the country, this is just a confirmation of the same old story. Russia is an authoritarian nation whose leaders are corrupt and self-seeking, whose populace is passive and impotent, whose institutions are eternally in decline. Their prescriptions for the malady—which never change either—are muddled and comfortably out of reach: rarely do they go beyond nostalgia for the Yeltsin years leavened with ritualized incantations like “multiparty democracy,” “civil society,” and “the rule of law.”

Meanwhile, the country is changing.

The Intellectuals

Among the most prominent and most-discussed Russian books of the past five years are two political novels of ideas, Dmitrii Bykov’s ZhD and Zakhar Prilepin’s San’kia. In the United States, this genre has died out almost completely; in Russia, it has become a bizarre amalgam of commentary on current events, lit-scene inside jokes, and grand metaphysical theories about the country’s past and future.

This usually leaves little space for compelling plot or nuanced characterization. In San’kia, written by an avowed supporter of the National Bolshevik party (known more for their stunt demonstrations and anti-government posturing than anything the name would normally imply), the titular protagonist is a young National Bolshevik whose life revolves around party business: beating up immigrants, being beaten up by bad guys from the state security services, and expressing angsty contempt for weak-kneed liberals of all kinds. Neither the liberals nor the government have any place in Prilepin’s utopian future—that much is clear. Less clear is what that future is actually supposed to be like. Beyond some vague and watered-down fascist platitudes about the rejuvenation of the Russian people, San’kia manages never to articulate a coherent positive proposal for anything. This is not a fascist book, and the vagueness is not a cover-up for any hidden totalitarian program. Rather, it seems to be the only suitably capacious political vision available in a world which is starkly divided between two unacceptable alternatives. The rhetoric is simply an admission of defeat, a confession that the author has been unable to find an idea worth fighting for.

ZhD, although it is satirized in San’kia, is in fact not substantially different. It depicts a future in which Russia is being fought over in a civil war between Nordic fascists, whose goal is the militarization and eventual annihilation of the Russian people, and Jewish liberals, whose nefarious plans appear to involve moral corruption and the eventual annihilation of the Russian people. In the meantime, the people themselves are passive and unable to escape the circular oscillation of the country’s past. (All of Russian history, it turns out, was produced by the very same struggle.) The enemies are the same as Prilepin’s—and the ideas are equally impoverished. After nearly a thousand pages of text, Bykov cannot come up with any new vision for the future except the need for escaping the cycle. He fills the lacuna with tacky anti-Semitic tropes and pseudo-patriotic sentimentality.

Curiously enough, Bykov is himself a Jew, which suggests that the novel shares its underlying problem with San’kia: fascist vocabulary is dragged in as a palliative for an ideological vacuum that neither writer quite knows how to confront. This indecisiveness—or rather, this decisiveness emptied of all its content—forms a stark contrast with the past of the genre. Nineteenth-century political novels of ideas, like Chernyshevsky’s What Is To Be Done?, at least had a sense that they were being written for a purpose. Even Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, for all its fabled polyglossia, and Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, for all its ironic distance, aimed to leave the reader with a sense of the landscape of ethical and political alternatives. Bykov and Prilepin leave her more confused about them than before.

In significance, Bykov and Prilepin are dwarfed by Victor Pelevin, easily the most successful and well-known Russian writer of literary fiction since the fall of the Soviet Union. (An online survey recently crowned him Russia’s leading intellectual.) Pelevin’s novels are also political, and they also deal with ideas—but they approach them from a different angle. Pelevin shuns scope and ambition; his novels, which come out every year or two, are intimately tied to their historical moment, to the headlines and scandals that fill the popular press. They also reveal the workings of a clever and educated, if somewhat impatient, mind: he is a kind of literary Zizek who quotes Derrida and Brezhnev in the same sentence and explains the Heart Sutra using the slang of Russian mafiosi.

Despite their numbers and the variety of their themes, Pelevin’s novels all have something in common. Their message, whether it’s delivered through a Ouija board by the ghost of Che Guevara or announced by a metatextual author-proxy to one of his characters, is always the same: politicians and activists are all bought and paid for, all political alternatives serve the same end, the demand for struggle and change is the naïve reflex of the uninitiated. This would sound like idle cynicism of the most unreflective kind, were it not for the metaphysical insight that always accompanies it. For Pelevin, the fundamental building block of existence is the dollar. We are, in his novels, simply machines, phantoms which lack any function or meaning other than the consumption of goods and images. The only hint at a liberatory practice is a kind of capitalist Buddhism, the recognition and self-annihilation of oneself as a consuming and consumed illusion—and since money is identical with reality, Pelevin’s novels rarely end with the world and its inhabitants ontologically undisturbed.

Somehow—and this is really the essence of his literary gift—Pelevin makes all this sound not only plausible but utterly self-evident. Although he wishes to destroy the landscape of alternatives instead of exposing it, Pelevin ends up painting a much clearer and more accurate version of it than any of his literary rivals. This is because he understands, unlike them, what has changed in Russian history in the past two decades: though its metaphysical status may be up for debate, the dollar remains the fundamental building block of Russia’s social and political life.

The People

There are a lot of cop shows on Russian television. There are, in fact, so many of them—most with stock characters and unimpressive budgets—that an uninitiated observer could be forgiven for assuming that they are part of some malevolent government program aimed at fostering support for the police state. But while it is true that Russian television is state-controlled, and nothing truly subversive would be allowed to become so incredibly popular, the reality is somewhat more complicated. From the point of view of the traditional liberal/authoritarian framework, the shows’ ideological message is ambiguous or even incomprehensible.

American cop shows and movies generally rely on a moral schema in which justice is the goal and laws and institutions are an obstacle to its realization. It is notable that this is equally at work in typically “leftist” productions like The Wire, in which the characters must manipulate or avoid the laws and institutions that perpetuate social ills, and in “rightist” ones like 24, where similar tactics are used to detect and defeat terrorist threats. Russian cop shows are very different. Justice, of course, is still the goal, and institutions are generally the enemy. What is being sought, however, is not justice in the abstract but rather justice through law. Characters who violate or bypass the law in pursuit of justice are not, as in American shows, turned into heroic protagonists: they are treated as unreliable allies at best and villains at worst.

This is, in a manner of speaking, a demand for the rule of law, though one without the traditional liberal invocation of civil and political rights. On the other hand, in a society as riven as Russia is by official lawlessness and corruption, the elevation of law-abiding police officers into cultural heroes is not especially surprising. What is surprising is that similar demands have begun to be raised in society at large. Russians are more solicitous than ever about the security of their lives and livelihoods, and they are more willing than ever to turn to institutions to protect them—even if they are increasingly reluctant to commit to broader political programs.

In short, Russians are acting, and becoming, more and more bourgeois. The explanation for this is simple. Over the course of the 2000s, due to the easy prosperity and cheap credit brought about by ballooning oil prices, the average Russian could feel herself getting wealthier at a rate no one could have imagined in the 1990s. The world around the average household, too, became visibly wealthier. Glitzy pink-concrete apartment buildings and shopping centers replaced ramshackle Soviet-era apartment blocks, and a colossal real estate bubble made many Muscovites possessors of million-dollar properties. That all this prosperity was largely illusory, and that it brought about little meaningful expansion of the economy’s real productive powers, seems to have mattered little. In Russia, the simulacrum often works just as well as the real thing—which became clear when the house of cards collapsed abruptly in late 2008 (the Russian economy was the worst affected of any country) and the cultural transformation remained.

The Russia of old was a paradise of ideologies. In the Russia of today, all ideologies are converted into their currency equivalent. When DDR memorabilia is sold on the streets of the former East Berlin, there is at least some recognition that a different ideology once existed in this space. Russians happily sell the symbols Soviet ideology to each other, but to them they no longer have an ideological meaning. “Soviet” now means simply “unpretentious, old-fashioned, conservative, domestic,” just as Romanov eagles and archaic lettering denote “European, luxurious, exclusive.” Thus a shoe store near my house bears on its sign a large hammer and sickle and promises “Fair Prices”—despite the fact that its customers are all aware that decent new shoes, never mind “fair prices,” were impossible to find in the deficit-ridden Soviet era. A recent film pits a superhero in a flying (Soviet) Volga car against a supervillain in a flying Mercedes, and the conflict is presented as a clash between human cooperation and decency and runaway capitalist competition. There is no revolutionary, political, or even economic component to their struggle, however: both of the film’s antagonistic sides, whether the creators realize it or not, are products of the same spirit of bourgeois sentimentality that animates contemporary Russian culture as a whole. Nostalgia for communism, in other words, is the ultimate sign of complete embourgeoisement—and that is, perhaps, why the handful of genuinely committed radical leftist parties looks so bizarre and lost against the cultural backdrop. The mainline Communists have learned that the time of Marx and Lenin is over, while the time of their pictures has only begun.

The State

In early August, as the fires were taking on truly catastrophic proportions, a Russian LiveJournal user groused about how his village’s fire-protection system, set up under the Soviets, was dismantled by the “democrats” and replaced with a non-working telephone. The general editor of “Ekho Moskvy,” a well-known liberal radio station, forwarded the post to Putin. The prime minister posted a comment in response:

Dear User,

Today, at the end of the working day, breathing, like all Muscovites, the smoke from the fires burning around Moscow, I was very pleased to read your evaluation of the situation with the forest fires in Central Russia. […] You are, of course, a wonderfully sincere and direct person. You’re just great. And you are, unquestionably, a gifted author. If you were to earn your living by writing, you could live, like V. I. Lenin’s favorite author—A. M. Gorky—on Capri. But even there you could not feel yourself secure. Because both in Europe and the USA natural cataclysms on the same scale are being confronted. […] Despite all the problems and difficulties, I hope that you and I will be able to get to retirement successfully.

What can one say about the political condition of a country whose leader could write a comment like this? Naturally, it is not simply a question of the king deigning to speak with a peasant. It is the very tone of the reply: its awkward sarcasm, its ironic reference to Lenin, its semi-facetious suggestion of a common “getting to retirement.”

If this comment is taken to be representative of an authoritarian political system, it is a very strange system indeed. For one thing, Putin’s comment does not come from a rhetorical position of authority. It is far more Woody Allen than Stalin. While he does offer to replace the fire alarm bell, he is not assuming the mantle of the Good Tsar protecting his populace. He resembles a socially-awkward middle manager more than the belligerent and repressive dictator of a seventh of the Earth’s landmass. In the meantime, Russia’s president gives uncomfortable television interviews about the need to establish trust between the citizenry and the police and to promote the rule of law, using language that could be taken straight from the website of a liberal NGO. Putin and Medvedev, if they are dictators, have become rather half-hearted ones.

What has begun to happen in Russia over the past decade is not too far from what right-wing foreign-policy experts always assumed. The growth of a bourgeois culture, if not strictly a middle class, has led to concern for the enforcement of individual rights, a new self-assertive sense of personal dignity, and an attitude of sated complacency about the issues Russians were once supposed to embrace with all the depth of their mysterious souls. Pace the standard narrative, however, the liberals aren’t getting their piece of the pie. In fact, even the “right-wing” (i.e. liberal) parties that were once supposed to be the voices of some hypothetically emerging petite bourgeoisie have fatally compromised themselves in the eyes of the actual petite bourgeoisie by signing on with the dissident-defenders and advocates of human rights in Chechnya. The New New Russian, it is clear, doesn’t care about any of that—which explains the comparatively enthusiastic support enjoyed by “The Right Cause,” a new liberal party funded by the Kremlin itself.

The intellectuals, like the liberals, were wrong. A Kremlin that funds its own quasi-opposition and leaves the Internet un-firewalled is not the Kremlin of old, even if it still knocks off dissidents. Russia isn’t stuck on a mammoth historical pendulum that swings implacably between liberal reformism and authoritarian repression. Like France under Napoleon, it has smuggled in most of the demands of the old 1989 Revolution under the cover of political conservatism, showy piety, and the hunt for contented wealth. And ideology, in Russia and in France, has gone quietly into that good night. The intellectuals might eventually see this—but first they would have to make enough money.

]]>

photo: G. Afinogenov

1

As you make your way through the Neues Museum in Berlin, you will find yourself walking through a room—the Roter Saal—that seems somehow different from all the others. The hall is dedicated to prehistoric artifacts, but displays here have no friendly bilingual plaques to explain their historical provenance or context, and they are not arranged thematically or even chronologically; in fact, they seem to have no apparent order to them at all. Tools and pottery fragments seem to be piled one next to another on simple, utilitarian shelves, like disused power tools in a suburban garage. The room is large, and that makes it even more unsettling. What could it be doing here, in one of the Europe’s slickest museums?

Moving through the Roter Saal at the rapid pace which it seems to demand, you are likely to miss something important: in the frame of history, it isn’t really the room that’s strange. If anything, it’s the museum around it. The role it plays now—providing culturally-satisfying edutainment for tourists—was at best secondary a century or two ago. More important was the museum’s function as a storehouse for classical antiquities, collected around the world by royal Prussian and imperial German archaeologists. Piles of ancient treasure, enclosed in a suitably imposing neoclassical building, served as a graphic link between political and cultural authority. The Neues Museum was not, of course, alone in this regard. The institutions that surround it on the city’s Museum Island—all built during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—were integral components of the same project. The crown jewel being the Pergamon-Museum, which contains most of a gigantic Greek temple as well as the monumental Babylonian Ishtar Gate. Even more obvious, perhaps, is the Alte Nationalgalerie, whose enormous collections of mediocre nineteenth-century German realists and Romantics are totally inexplicable until one realizes how literally its name is supposed to be taken.

These buildings, of course, no longer exist in their old context. Today, they function as tourist destinations, as members of a long list of “sights”—from concentration camps to dance clubs—that visitors to Berlin are expected to see. Yet something in them remains unsettled: as the Roter Saal reminds us, they exist as spaces out of joint with their time, subsisting uneasily as links to moments that are not simply outdated but, in effect, unassimilable. They provide us with an opportunity to question not only how the city copes with such irruptions of anachronism, but also the conditions of their apparent necessity. We need these places, but we don’t know why.

2

On an upper floor in another of Berlin’s museums—the Märkisches, devoted to the city’s history—there is a strange polygonal contraption of dark wood that occupies half of a large room, periodically ringing and whirring. The machine is a stereoscope. Sitting down on one of the chairs surrounding it and looking through the binocular lenses that protrude from each of the sides, the visitor is treated to a sequence of three-dimensional photographs, some in color, of Berlin around the turn of the twentieth century. The effect is achieved very simply (the image presented to one eye differs slightly from the other), but it is a stunning illusion of depth.

Living as we do in the post-Avatar moment, it is easy to appreciate the 3-D technology of this bygone era. The photographs are truly lifelike; in one of them, a lower-class boy looks directly at the camera, and his accusatory stare locates us in the place of the photographer, whose boxy flashes and tripod legs we can glimpse in some of the other pictures. The realism of the street scenes is rendered even more uncanny by their familiarity: though the cars and outfits may be different, they feel viscerally recognizable in a sense that simple photographs from the period cannot convey.

The illusion is a slippery one, however. Many of the photographs are of military parades, coronations, and other state events, and their world remains almost totally unfamiliar no matter how real scenes seem. The pudgy Kaiser in his spiked helmet and the cavalry guards with their shakos belong, naturally, to a different time. But the buildings are even more alienating. It is one peculiarity of stereoscopic images that the people, though arranged and positioned in a three-dimensional space, seem insubstantial, like cardboard cutouts in a photorealist diorama. The same cannot be said of the buildings. In the pre-war, pre-Bauhaus moment of the Second Reich, in which Corinthian columns, massive domes, pediments, and arches remain necessary components of official architecture, the effect is of a city made for buildings rather than people. Or rather, perhaps, of a city of people made for buildings. Even the parades seem intended to underscore the parade-ground and not the other way around. Within the bowels of the stereoscope, in short, paper-thin shadows populate an urban space still dominated by the presence of imperial classicism.

photo: G. Afinogenov

It is in this respect that the stereoscope’s photographs hearken not towards the 3-D future of Avatar, but to the geometrically rigid, linear space of eighteenth-century painting, a collection of which hangs only a few rooms away. These are eighteenth-century views of Berlin, primarily of the axial avenue Unter den Linden and the squares in its immediate vicinity, the similarity to the stereoscopic photographs, though not immediately obvious, soon becomes apparent. Following the conventions of the genre, each view is filled with people: strolling aristocratic pairs, merchants going about their business, and so on. Once again, however, these inhabitants of the foreground are rendered insubstantial. Rarely looking forward, they are not furnished with any identifiable personalities and are, from view to view, entirely interchangeable. Again, the protagonists are the buildings themselves: blunt demonstrations of Berlin’s growing wealth and power, their columned authority is the raison d’être of the very paintings in which they are depicted. The lovingly rendered urban landscape, in the hands of these artists, is no place for people either.

These, then, are the outlines of the world in which Berlin’s classical museums once existed—a world where classicism, imperial ideology, and official culture combined to project the authority of the state over the urban space. Today, little heed is paid to the inherent authority of architecture: Berlin’s municipal authorities happily coat structures in scaffolding and then drape the scaffolding with ads. (When I was last there, a restaurant-style chalkboard stood in front of the mammoth portico of the Altes Museum, pointing inside and promising “coffee to go.”) It is in the street and with the pedestrians that authority now lies, because it is there and not in state-funded rotundas that the market can live. Yet there was also once a third alternative, which has itself become nearly incomprehensible to us today: the Berlin built and imagined by the DDR.

3

Less than a block from the Märkisches Museum is yet another museum, which contains twentieth-century scale models of central Berlin. There is rarely anything surprising about scale models, but the one built by the East German government in the 1980s is undoubtedly the most interesting. Unlike the larger model in the same room, it isn’t totally white, and comprehensiveness is not its overriding goal. Instead, as presented, it serves as a kind of self-enclosed, self-sustaining ideological justification for the DDR. The Fernsehturm TV tower (deliberately built, as any tour guide will tell you, to be slightly shorter than the Ostankino tower in Moscow), equipped with a baneful red LED reminiscent of nothing more than the Eye of Sauron, dominates the 1:500 landscape. It looks out over an idealized East Berlin in which the historic city center has merged harmoniously with socialist buildings, presented in a way that obscures shoddy construction and rapidly graying walls. Curiously, though, the old classicist edifices are not forgotten; indeed, they’re reproduced even more carefully than any of the new apartment blocks.

photo: G. Afinogenov

East German ideology understood the significance of such spaces more intimately than its Western counterpart. The Democratic Republic’s first major project was the 1949-‘51 construction of the Stalinallee (later renamed the Karl-Marx-Allee) in its half of Berlin; like its counterparts in the Soviet Union, it was executed as a grand boulevard in the nineteenth-century mold, with its apartment towers following the conservative stylistic codes of High Stalinist classicism. The attempt amounted to a strategic alliance between architecture, in full bloom under the Second and Third Reich, used to dominate public space and the traditional late-socialist obsession with massive projects oriented towards consumer goods, economic contentment, and the standard of living. DDR ideologists seem to have understood the link instinctively, and they worked hard to maintain that effect. The East Berliner who walked down the street to his apartment would be made to associate this coveted middle-class possession with the ideological claims made by its architecture. This was state classicism in the service of a fundamentally economic ideology; the very language of its construction suggested the filial piety of socialism to the Empire from which it inherited its style. This is almost impossible to reconstruct today: there are now so many stores in the lower levels, so many advertisements at human height, that the street as it was once envisioned is literally invisible.

photo: G. Afinogenov

Subsequent socialist decades brought new projects, not all of them with the same aesthetic, but the focus on Imperial history remained. Two of East Berlin’s largest cultural/construction programs in the last decade of its existence—the restoration of the eighteenth-century Gendarmenmarkt and the generously interpreted “reconstruction” of the medieval Nikolai Quarter in the city center—were deliberate gestures, efforts to stake a claim to the legitimate management of historically as well as politically-invested space. (The giant city model is another such demonstration.) A tourist attraction such as the new Gendarmenmarkt could not, in the East German understanding, be simply a tourist attraction, and that made it more similar to its imperial predecessor than it was different: despite the radically opposed content of their ideologies, both embodied them in structures invested in history and positioned outside and above the fabric of street life. The fall of the Berlin Wall, then, meant more than the end of a physical or a bureaucratic structure. With the city reunited, the authoritarian classicism that had once shaped it was swallowed up and submerged by the newly assertive street.

4

On Potsdamer Platz, which was once a bulldozed wasteland through which the Berlin Wall ran, there are now enormous glass skyscrapers. Built, it would seem, as a parody of socialist megalomania, the Sony Center encloses a space only slightly less alienating than the Wall itself. Everything is outsized, and what isn’t beyond the power of the eye to compass is certainly beyond the power of the wallet. Even the tourists look a little shellshocked.

In a corner of the square, however, there is a monument which looks peculiarly out of place. It is a simple fragment of smoke-darkened stone wall, bearing the inscription: “From this position, on May 1, 1916, Karl Liebknecht called for struggle against the imperialist war and for peace.” On top on the inscription there is a plaque, a little lighter and newer, that informs the visitor that it was put up in 1951, taken down in 1995, and restored “with commentary” in 2003. (The commentary, it seems, is the plaque itself.)

And then, of course, there is the Wall. Although it has been gone for twenty years, reminders of its existence are only becoming more insistent: it is painted redder in the tourist guidebooks, the souvenir stands are more obnoxious and omnipresent, the Checkpoint Charlie gimmicks are more inventive. Unlike the former Nazi buildings in Berlin, the Wall is not sequestered away behind glass as something to be memorialized at a safe distance. Instead, it is constantly resurrected as it is celebrated. Sections of Wall still stand along the tourist routes; on Potsdamer Platz a fake East German immigration officer will stamp your passport with an “official” DDR stamp; the only souvenirs on offer are pins and flags from the Soviet Bloc.

What possible motivation could there be to preserve the Liebknecht monument and the “authentic experience” of the Wall? It certainly is not serving any political end, for whatever these structures may represent, they have been drained of all political significance by their gleefully capitalistic tourist-trade context. Just like the Neues Museum, the old socialist sites are preserved as spaces out of joint, belonging to a world that cannot now be reconstituted. There are, perhaps, many explanations for each such act of preservation—a liberal hope for enlightenment, the hunt for tourist dollars, a simple unwillingness to disturb a historic site. But they are all representative, it appears, of something more fundamental: the inability to let go of history.

Nietzsche writes in The Dawn about the Romans, who built “with the ‘air of eternity’ in the back of their minds “We, who know only the ‘melancholy of ruins,’ can barely comprehend this very different melancholy of eternal buildings.” We, who once knew the melancholy of ruins so well, can no longer understand it like the Germans of Nietzsche’s day did: they, after all, were the ones who built so many dark, columned palaces to hold fragments of broken columns. We have given that up now—and what we have gotten in return is, in the end, something like his “melancholy of eternal buildings.”

photo: G. Afinogenov

History no longer has a direction: it moves neither towards imperial hegemony, as the various incarnations of the Reich imagined, nor towards communism. In that sense, Francis Fukuyama’s much-maligned argument about “the end of history” has turned out to be correct. Fukuyama thought history had ended because liberal democracy no longer had serious and powerful ideological antagonists; only dimly did he appreciate the ultimate implication of his argument, which is that liberal, capitalist democracy is no longer a serious and powerful ideological antagonist to itself. Seldom do we, or the Germans, invoke the utopian elements of capitalism or even of democracy any longer, and free-market absolutism, which represents the central utopian impulse of capitalism, has seen most of its intellectual defenders die off without credible issue. At this, perhaps the moment of its greatest strength, late capitalism resembles nothing so much as late socialism: a system too stubborn to die and too stupid to be reformed.

In a world such as this, it is little wonder that we spend so much effort polishing and reassembling these buildings—tombstones of an increasingly meaningless past. We feel the “melancholy of eternal buildings” because there is no longer any impulse to wipe the slate clean. The bare fact of a structure’s great age is sufficient to generate preservationist sympathy for it. (Even the anarchist squat Köpi has a ballroom that was once, supposedly, used by the SS—and this is a point of pride, not an excuse for renovation.) Having lost confidence in our present and feeling no compulsion to embrace the future, we collect endless reminders of the past, and our cities become pockmarked with its remains. Our buildings are eternal, and melancholy, because we can think of nothing else to do with them.

And yet, of course, we cannot bring the past to life. For us, the street is the city; it envelops and shelters us as we move through it, constantly reminding us that the purpose of our built environment is the facilitation of buying and selling. The buildings we encounter, no matter how grand or imposing they look, are always in dialogue with the street. They entice visitors, make claims to authority, coquettishly cover themselves with security; they do not command or dominate, as imperial classicism was once supposed to do. Despite all its anachronisms, therefore, Berlin is a city in which it is almost impossible to believe that anything other than our world ever really existed: the ghosts of the past are so feeble that we may as well have only imagined them. The Roter Saal still seems like a clear window into our culture—but this time, we are the artifacts on its shelves.

]]>

via the Daily News

Hardly a day goes by in our networked world without some new story coming out, somewhere, about “privacy.” Some people don’t like what Google is recording about them; others are angry at Facebook for making public what they had thought was private. Whether the story deals with identity theft or lost databases, browser settings or online advertising, snooping on shoppers or hacking into celebrity cell phones, it goes into the same bucket—and the bucket keeps getting bigger. Like spam, commentary and metacommentary on “privacy issues” as a percentage of Internet traffic must now be well into the double digits.

The booming market for such reporting, and its rapid and increasing penetration into what can now only historically be called “the mainstream media,” hints at what “privacy” really means for the Internet’s intellectual economy. Like pedophiles, cyber-bullies, Nigerian princes, and Russian hackers, corporate “privacy violators” are part of a long and growing succession of vague threats that periodically appear to menace Internet users—with the resulting moral panics serving mainly to justify ham-handed and instantly obsolete attempts at state regulatory intervention. In the past, such panics have almost always been linked by a common thread: the danger of abandoning “authentic” and “real” human contact for the open spaces of the Internet, where everything is somehow all too easy. It is to be expected that culture would find ways of representing such an obviously disruptive technology as a series of phantom threats; each largely unimportant in their substance but vital for creating a concrete, human locus for fear and suspicion of technological change. (As computer technicians constantly complain, users hardly ever implement effective security practices on their computers, but they are quick to blame viruses and hackers whenever a problem appears—a clear sign that we are dealing with a psychological projection rather than a specific problem.)

But privacy is a much bigger issue, and the cast of characters is correspondingly larger. The traditional role of scary non-Anglophone criminal type is filled here by the mysterious “identity thieves,” who probably get much of their menace from the Body Snatchers imagery the label inevitably suggests. Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO of Facebook, is the mustache-twirling, unscrupulous businessman, an identification continually propped up by new revelations about his past sleaziness (it doesn’t help that he’s a Harvard boy). And then there is, of course, the threat of the totalitarian, omniscient state, from the Chinese with their Great Firewall to the British and their networks of security cameras. In the privacy bucket, this cultural mulligan stew mixes with all kinds of other ingredients, from vaguely remembered tenth-grade readings of Nineteen Eighty-Four to even vaguer memories of the Supreme Court decision in Griswold v. Connecticut. Combine all of that with the personal associations conjured up by the word “privacy”—your parents reading your diary, being caught masturbating, your sister listening in on your telephone conversations—and the result is a toxic mess capable of engendering hysteria and paranoia in any quantity desired.

Maybe it is because of this that the specific arguments around the privacy issue are so universally confused. Commentators generally like to present themselves as plain old-fashioned folks who believe in the good ol’ values of privacy which kids these days have so irresponsibly abandoned. At that point all coherence ceases; if the commentator even bothers to provide a motive for his opposition to some privacy-destroying cataclysm or other, it is almost always in the form of an undigested innuendo about corporate authoritarianism. In the process, several different types of issues are conflated into one problem: data protection, which is above all a matter of security policy; data collection and indexing, which raises problems of centralization; and data privacy, strictly speaking.

The first is so technical that functional solutions are almost never offered in commentary. In fact, awareness of the issue seems to emerge at all only when someone loses a laptop or when identity theft becomes the hot-button issue of the week. With respect to data collection, however—and here the culprit, most of the time, is Google—the situation is radically different. It often suffices to simply accuse someone of collecting information (search data, shopping patterns, demographics) for all the toxic bubbles of suspicion to float to the surface. Surely you’re not in the business of making money off of information? Why would you need so much information anyway? And can you really not tell if it’s me buying the Hello Kitty vibrators?

This last genre of query is especially significant, if only because it recurs so often. Google and the other usual suspects, when faced with such questions, immediately hasten to assure doubters that their information is strictly anonymous. They are rarely believed. The rhetorical strategy of the corporations is thus always to differentiate data collection from issues of privacy, while that of their critics is the opposite. From the point of view of Google, this only makes sense: if your goal is to collect and analyze information en masse, then the identities of individuals (not to mention their names and Social Security numbers) are of tertiary interest at best. The end of the Google horizon is not the Orwellian nightmare of complete dossiers, available at the touch of a button, on any person in the world; it is rather the old social-scientific dream of universal quantification, prediction, and generalization.

But if the objectives of Google diverge so widely from what privacy crusaders think they are, why does the debate keep returning to the same familiar set of rails? What leads critics to evoke, so strenuously, the specter of Orwell’s telescreens? This is a question than can be answered only from the perspective of the privacy debate’s third aspect: Facebook, or the publicization of previously private data. On the surface, this controversy, which is perhaps the loudest and most visible, is also the least comprehensible. People who have deliberately given their data—their “likes” and “statuses,” their photos and self-descriptions—to somebody else, according to the norms of pre-Internet communication, cannot expect to have much control over it in the future. Enough old proverbs (for instance, “three can keep a secret if two of them are dead”) testify to this that demanding the contrary seems absurd.

And yet, of course, to an increasing number of people it is not absurd. Unlike Internet communication, pre-Internet communication presupposed the existence of separate, variably permeable spheres, which could be maintained with little effort and fantasized about with even less. (There’s an old Eudora Welty story about a man who leads a double life, with one life ultimately as restrictive and conventional as the other. Historically, I’d venture to say, this has been closer to reality than the utopia of closets evoked by some privacy activists.) For the privacy activist, unease with Facebook is usually founded on something much more mundane than Nineteen Eighty-Four: quite simply, the increasing difficulty of telling the little white lies that help most of us keep our spheres apart.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, however, the proposed solution in the privacy debate has not been to bow to historical inevitability and join in a mass experiment to remake our idea of the boundaries of social experience. Instead, the suggestion that permanent and omnipresent Internet access will in fact remake these boundaries whether we like it or not has been treated as seedy and disreputable, something like a trendy contrarianism possibly spread via dirty corporate dollars. The virtually universal resistance among privacy advocates to such a line of argument—which, corporate-funded or not, would at least recognize the Internet as a space of potentialities rather than simply of threats—has strongly narrowed their rhetorical field.

Indeed, apparently the only option left to them has been to circle the wagons in defense of positions they must constantly construct as traditional: suspicion of most forms of digitization, pressure to regulate or curtail electronic data-collection, and a legalistic paranoia about the privacy policies of key corporate actors. (Although such standpoints are, in fact, frequently represented as traditional or traditionalistic, the only “tradition” they really fit into is one of free-floating psychological conservatism.) Out of these and other fragments of value-discourses there is gradually emerging a kind of electronic Jeffersonianism, which is resistant to corporatization and commercialization, focused on the opposition between the individual user and the institutions that govern her Internet experience, and, paradoxically, inclined to privilege “low-tech” interactions (email) over “high-tech” ones (Twitter). (On the more technical side, this often translates into free-software advocacy and an interest in developing reliable and widespread encryption and data-protection techniques.)

Internet Jeffersonianism might appear to be a satisfying and compelling position, especially for people who, for whatever reason, are uncomfortable with the rabid capitalism of the Internet world. It is still, nevertheless, in large part a product of the bucket, a barely coherent and technically fuzzy result of fear, prejudice, suspicion, and insecurity. (The ideological climate in which it has developed has been such that any better result would have been unthinkable.) And there is also a more specific reason to mistrust it—for its central concept, in defense of which every privacy advocate rallies, cannot serve as a moral anchor at all.

This concept is, of course, “personal information.” What does “personal information” include? Phone numbers; Social Security numbers; addresses; bank account numbers; credit card numbers; biographical details; places of employment. The more specific and precise—the more quantified—a piece of information is, the more valuable it is for privacy advocates. Hardly anyone is up in arms about Google indexing childhood memories shared on Internet forums or Facebook making profile pictures public. Because these bits of information are hazy, indefinite, useful only for the most suave and intellectual of identity thieves, they receive little attention. The credit card number and the Social Security number, in contrast, have become the waving banner and the supreme stake in any true privacy debate.

They are also the symbols of another process, one of the gradual unfolding and expansion of institutionalization centered on information processing, quantification, and database-building. The Social Security number—which was introduced with the Social Security Act along with the solemn promise that it would not be used as a unique personal identifier—is the central driving force behind that process on the government side, and with the growing information-density of digital data it will likely soon be joined by biometric and other descriptors. The credit card number is the corporate analogue, and it is no accident that the in-depth transaction analysis it allows is one of the central issues of this side of the privacy controversy.

In short, the Internet Jeffersonians cannot stand athwart history yelling “Stop!”, because what they are defending from corporate and government interference is a central element of the very processes of institutionalization and commercialization they so fiercely oppose. The contemporary sense of “privacy” itself—the security and sanctity of the Internet-connected individual—could only have come about because technologies and practices like Social Security numbers made the individual institutionally legible in the first place. This is why the new Jeffersonian rhetoric so frequently rings hollow: it can never quite admit that its own ideology presupposes a much more radical “traditionalism” than is allowable.

Is there a better alternative, a theory and program for the Internet that could understand Google and Facebook without making the Jeffersonian mistake? There will, I think, be one soon. It is true that the Internet has largely outgrown the euphoria and utopianism of its early years, and as a space with some putatively inherent subversive potential it leaves more and more to be desired. At the same time, American culture and society—no matter how strange it seems to say so—have lagged behind the Internet’s development. Only within another generation or so will we see how corrosive or creatively destructive the Internet’s effects on human relationships will really be, and only then will we be able to make sense of the whole business. In the meantime, Google and Facebook, while not an especially palatable avant-garde, are the only real one that we have.

]]>

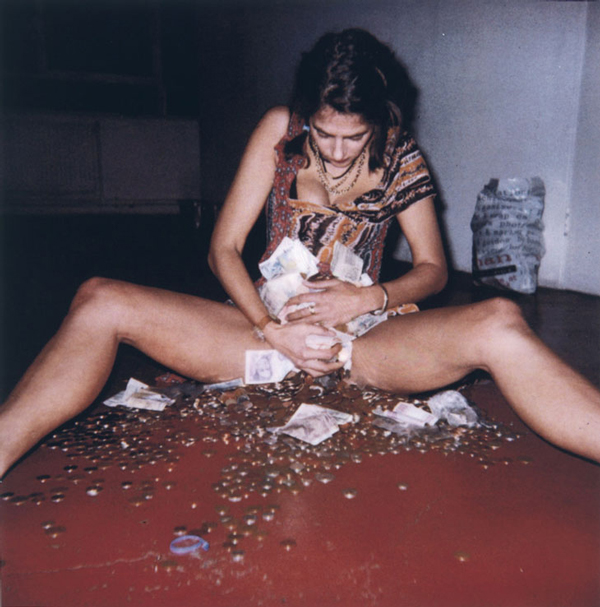

Tracy Emin, I've Got It All, 2000 via artnet.com

In a now-forgotten pamphlet about Feuerbach, Friedrich Engels looked back contentedly on the revolution his predecessors had produced in the history of philosophy:

The great basic thought that the world is not to be comprehended as a complex of readymade things, but as a complex of processes, in which the things apparently stable no less than their mind images in our heads, the concepts, go through an uninterrupted change of coming into being and passing away … has, especially since the time of Hegel, so thoroughly permeated ordinary consciousness that in this generality it is now scarcely ever contradicted.

And a fine thing, too! But Engels, being a good sport, lets the enemy have a point or two as well:

The old method of investigation … which preferred to investigate things as given, as fixed and stable, a method the relics of which still strongly haunt people’s minds, had a great deal of historical justification in its day. It was necessary first to examine things before it was possible to examine processes.

The past was prologue, however, and we had now no longer any need for the fixed and stable things of the eighteenth century.

Were Engels to read Ben Davis’s “9.5 Theses on Art and Class,” written and circulated in early 2010, he would no doubt be shocked out of his complacency. He would immediately recognize, of course, the phrases that he and Marx had coined so long ago: “working class,” “relations of production,” “class interests.” Something of the style would also seem faintly like his own. Indeed, to Engels’s undead eyes the strangest expression would probably be “middle-class,” used by Davis, it seems, in place of “petty bourgeois.” (This appears to be purely an attempt to avoid ringing too many ideological bells at the same time, although it is only partly successful.)

Almost everything would be familiar—and yet everything would be strange. Where is the history, the development of these concepts? What is the actual structure and composition of the “working class,” on the basis of which it participates or does not participate in the art world? What means of production does the ruling class really control, and where do its mysterious “ideologies” really come from? Can it really be that the terminology and analytical framework that emerged in the course of Marx and Engels’s historical investigations could have survived through a hundred and fifty years only to end up in Davis’s theses, virtually unchanged? Engels’s declaration of victory over metaphysics, it would seem, was premature. We remain in 2010 still in the thrall of fixed and stable ideas, and questions of process are nowhere in sight.