still from A Dangerous Method, courtesy of HanWay Films

I.

Is cinema neurotic? Certainly it is prepossessed by images of its own death and Oedipal strangeness. Let’s examine the year’s critical darlings.

First, there’s Hugo. Martin Scorsese’s ultra-Oedipal pop-up book depicts the travails of an orphan whose maltreatment functions as a cipher for the neglect of film. Painfully self-aware, Hugo mutates into a curious essay featuring George Méliès, Hugo’s substitute father who is also a Father of Cinema. The subject of the essay? The childhood of film and its probable death by decay.

If Hugo presages film’s eventual death, then Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives hosts its funeral and digital afterlife. In Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Palm d’or winning take on the Phaedo, the dying Uncle Boonmee — like Hugo, a stand-in for celluloid — is visited by a gallery of filmic shades who help him realize that repressed memories of death and murder lie at the root of his fatal illness. When Boonmee dies, his digitalized survivors learn to duplicate themselves like image files, in effect transferring generational struggle from the Oedipal (fathers and sons) to the technological (filmic shades to digital copies).

In Melancholia, there is no afterlife. Although Lars von Trier’s unsparing demolition of the European family expands into an allegory about the state of the states of the world, Melancholia is also a fairy tale about the entrapment of magical thinking, the neuroses transferred between mothers and fathers to their children, and, most importantly, the failure of our instruments of vision — cinema — to prevent the slow crawl of an ever encroaching gloom.

And Melancholia wasn’t the only film to link the family drama with cosmic death as a form of cinema. In Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, a contemporary man-without-qualities revisits his childhood by way of an overwrought fantasia, one where his own Freudian hang-ups (struggle with father, sexual adulation of mother) are superimposed over the juvenescence and cold death of the entire solar system.

II.

Caught between the death of film and a digital childhood, in a neutral era, and beset with interactivity and the proliferation of digital imaging technologies, it would appear that cinema has developed a debilitating neurosis. In recent years, cinema found itself torn from the (photographic) indexicality that sutured its relation to memory and history. Indexicality ensures a certain family resemblance between the image and its material source. Without this family resemblance, it seems, cinema became unsure where it came from or where it might be headed. It simply no longer had complete faith in either its instruments of vision or its predictive faculties. As a result of this bad faith, film has become preoccupied with that which overwhelms basic human capacities: accidents, disasters, superheroes. On the other end of the spectrum, film began to rely on the archival power of Arks and museums. To put the whole issue more succinctly, cinema is now wrestling with its digital unconscious, or as Godard says in his own Ark-work, Film Socialisme:

We’ve entered into an era with the digital wherein, for different reasons, humanity will be confronted by problems which will not have the luxury of being expressed.

And yet, if cinema is in a neurotic, even hysterical state, in 2011 it also found itself in the throes of a talking cure. The aforementioned films, alongside minor works like The Artist and The Future, show cinema in a spectator position, one that visits the very sites of its production: scenes of birth (George Méliès in Hugo) and childhood (the silent era in The Artist) and telluric death. Even this telluric death must be understood as an act of self-excavation on the part of cinema, for the colliding planets and collapsing stars of 2011 were always seen through telescopes or other instruments of vision (Melancholia, The Tree of Life, and Nostalgia for the Light).

still from Hugo, courtesy of Paramount Pictures

III.

The neurotic condition of cinema is literalized in extremis by David Cronenberg’s excellent A Dangerous Method. If in 2011 cinema was prone to fits of transference, that is, if cinema redirected its anxiety in the form of unwieldy fantasias and shifting subject positions, Cronenberg’s film plays out as a meta-commentary, like an analyst’s tidy notes regarding the condition of the analysand. A Dangerous Method is, for lack of a better expression, Melancholia‘s shrink.

Like Melancholia, A Dangerous Method explores the relationship between the caring and the cared-for. Cronenberg uses wide angles and split-diopter shots to frame his neurotics, thus maintaining a doctoral, even totalizing gaze, in opposition to Von Trier’s ecstatic, trembling eye. His faith in these instruments of vision leads him to a startling discovery: a paradox that cuts deep into the skin of contemporary cinema. The paradox of A Dangerous Method is precisely not one of repressed anxieties regarding childhood and death. Instead, as the title suggests, it is one about method and pedagogy. Cronenberg’s film slyly substitutes the relationship between doctor and patient for an analogous one between master and pupil.

Cronenberg’s Jung is beholden to Freud because of his position as father of psychoanalysis and master pedagogue. Freud, who is searching for an intellectual heir, likewise needs Jung, who, in the process of breaking away, also teaches Freud a lesson on the power of class. Add to the mix a few sermons on the perils of sexual repression delivered by the self-professed neurotic Otto Gross — who later became a major anarchist thinker — and the sex-and-death epiphanies of the once hysterical Sabina Spielrein: it all amounts to an Olympiad of pedagogical gamesmanship.

In A Dangerous Method, the lessons exchanged by Freud, Jung, Gross, and Spielrein are inextricable from their neuroses. The childhood events that shaped them, their sites of production, are excavated as memories and translated through the talking cure. This process of excavation and translation transforms these memories into pedagogical material: sites of production become, literally, scenes of instruction. And so Sabina Spielrein metamorphoses from hysteric to brilliant student to thriving (and pregnant) psychoanalyst. Yet the film concludes at an impasse, a fascinating deadlock with repercussions for the age of extremes that followed Freud and Jung, one borne of an almost unconscious debate within contemporary cinema. In the film’s final moments, Jung accuses Freudian psychoanalysis of suspending its patients in ignorance, of keeping them “squatting like a toad” — an allusion to Milton’s Satan — at the mercy of an equally ignorant analyst. To go further, one must actually teach the patient the method for curing his neurosis: Jung believes this should be the goal of psychoanalysis. Cronenberg, who obviously sides with Freud, shrewdly links Jung’s modus operandi with the rise of Fascism. Against Jung, the cure offered by Freud (and by extension, Cronenberg) is not a prescription forced onto a patient. It instead resides in an invitation to autonomous activity. The cure for neurosis lies in the patient’s act of translating his illness through the language of childhood memories.

IV.

The debate at the heart of A Dangerous Method has begun to contour the form of individual films. In fact, the year 2011 in cinema was characterized by the ascension of a particular strain of pedagogical form — the essay film — within the body of narrative cinema. Even a sidelong glance at the year’s critical favorites confirms the renewed vigor of the essayistic. At least five of Film Comment’s top twenty films of last year are heavily essayistic in structure (The Tree of Life, Uncle Boonmee, Hugo, Nostalgia for the Light, and Film Socialisme.) In Film Comment’s 2010 list? Zero.

The rise of the this genre is well documented in Timothy Corrigan’s new book The Essay Film (2011). Corrigan formulates the essay film as a:

1) testing of expressive subjectivity

2) through experiential encounters in a public arena,

3) the product of which becomes the figuration of thinking as a cinematic address and a spectatorial response.

In other words, the essay film is a kind of thinking-out-loud through images, one that results when subjectivity is questioned in a public encounter. Given the transitional nature of cinema and the Hulu-ification of its public, it is no wonder that cinema has taken to the essay form to express its neurosis. A similar formal development occurred with the rise of video and television, the apotheosis of which was Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma. Godard’s essay, instead of merely lamenting (as we do now) the loss of celluloid, attempted to think through this loss by reconstituting the cinematic image with a fraternity of metaphors: the symbols and icons collected by cinema among other arts, as well as the infinite number of linkages between them. Godard accomplishes this feat, as Jacques Rancière points out in The Future of the Image, by having his images “appear, vanish, intermingle” according to the operations of video. Through this process of translating between images, of thinking through cinema, Rancière says, “Godard fashions the cinema that has not existed.” That is, until the current reprisal of the essay film. It is telling that Godard’s masterwork, still the preeminent essay film, finally found American distribution in 2011, thirteen years after its initial release.

The third part of Corrigan’s formulation, concerning cinematic address and spectatorial response, is perhaps the most salient with regard to the resurgence of the essayistic. This is because matters of address and response characterize the relationship between doctor and patient, master and pupil. Although not itself an essay film, A Dangerous Method taps into this current. The film works as a kind of framing device, one that magnifies a temporary split within the essay form.

On one side of this divide is what we might call the Jung school. These films, among the most neurotic, advocate a heavy-handed didacticism, one that tries to hide its lesson within narrative camouflage. Deeply neurotic works like Malick’s The Tree of Life and Scorsese’s Hugo are narratives only in the cosmetic sense. Beneath the surface, Malick’s film is a theodicy that defends the existence of an America torn between nature and grace. And Hugo is simply a film studies monograph disguised as a children’s story.

The Jung school seeks to cure cinema by forcefully realigning the spectator within a given tradition. This is why Hugo becomes a lecture on film preservation, one where the protagonist confesses his disturbing wish to find his place as a cog in the great machine of the world. In Malick’s case, the proposed tradition is a species of American pragmatism. In particular it is a pragmatism preached by his mentor, the philosopher Stanley Cavell. The critical obsession with locating Malick within the Western philosophical tradition (Heidegger and Cavell) should itself be seen as a symptom characteristic of the Jung school, one that privileges the hierarchical position of master-pedagogues over ignorant students. Amazingly, Cavell, who is really the Malick of philosophy, had at least two adulatory pieces on his teacherly charisma published this year alone. All things being equal, the dominance of The Tree of Life in 2011 tells us only one thing about contemporary cinema: its critics are everywhere in search of a master.

The search for a master helps explains why so much of critical response to The Tree of Life often took the shape of the apologia, that classical form of religious pedantry. The exemplar of this approach was Adrian Martin’s Manichean defense of The Tree of Life in FIPRESCI, “Great Events and Ordinary People,” where he assures dissenters that the film is a perfect auto-summary, a monadological masterpiece wherein each moment explains all others. Hilariously, by way of a neurotic hiccup, Martin then embarks on the first harrowing steps of his own talking cure. He wonders aloud whether his namedropping of Western philosophers might be getting in the way of his appreciation of the films:

Most articles on Malick (mine included) like to heavy-hit from the outset with a prefatory nod to a Great and Deep Philosopher: Heidegger, Plato, Weil, Cavell…Yet, while we know that Malick has swam in these waters, I wonder whether, with the years, he has also worked (this is pure speculation) to divest himself of some good deal of this apparatus of learning…this cultural and intellectual sophistication.

Next, as if to confirm cinema’s obsession with childhood and talking-cure-stage neurosis, Martin whispers the secret hidden within the heart of every critic enthralled by The Tree of Life. He likens Malick’s film to Eden before the animals were named, before our adult identities are fixed, badly congealed, inescapably neurotic. It is like reading Daniel Stern’s The Interpersonal World of the Infant, with its system of ’emergent senses of self’ all co-existing in the same growing child, that lurks around forever despite our best efforts at erasure and repression.

still from Film Socialisme, courtesy of Wild Bunch

V.

Positioned against The Tree of Life and its apologists is Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme, the best of what I’m calling (after Cronenberg’s A Dangerous Method) the Freud school, which presupposes the egalitarian nature of intelligence, the capacity of the spectator to translate between unlike things.

In a press conference for the film, Godard cited Jacques Rancière’s The Ignorant Schoolmaster as a catalytic text (and not a master document). Rancière’s book excoriates what it labels the “circle of power” within the Western pedagogical tradition. This circle of power is nothing other than that which ties the student to his Old Master. Rather than assert an equality of intelligences, the Old Master traps the student in a circle of powerlessness, one that requires the Old Master as an explicator of texts. Against this grain, Godard in Film Socialisme tells us that “we can only compare the incomparable from the comparable.” And Rancière, too:

The student must see everything for himself, compare and compare, and always respond to a three-part question: what do you see? what do you think about it? what do you make of it? And so on, to infinity.

The job of the teacher, like the Freudian psychoanalyst, is simply to provoke a belief on the part of the student in his power to compare, to translate away his illness or his ignorance. This ethos frames a key section of Film Socialisme, in which a pair of young, auto-didactic siblings — anti-Hugo’s — hold their parents to a “tribunal of their childhood.” It also explains the critical response to Film Socialisme. Unlike the pedantry that followed Malick’s The Tree of Life, the reaction to Film Socialisme was a wave of translation and comparison. The film’s truncated Navajo-English subtitles were quickly replaced with full-bodied translations. Then an anonymous French collective began to trace the web of motifs and signifiers that Godard weaves between his many characters. Later Lumiere, a Spanish publication, collected the fruits of this labor, expanded upon it, and republished it. Recently much of this annotation was translated into English by the industrious David Phelps for Moving Image Source.

Annotation, translation, collective labor: these are the tools required to rebuild a community, or to cure a vicious bout of neurosis. With cinema in such a state, Godard could have easily slipped into melancholy, or proclaimed his status as Old Master. Instead, surveying the terrain of Europe, Godard fixed his gaze on the Mediterranean. Then he set to annotating, translating, laboring. To infinity; to a constantly receding horizon.

]]>

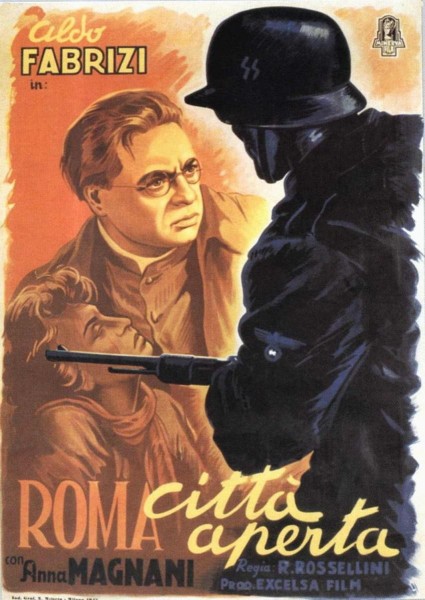

Original Poster, via Film Affinity

A supply of images would become the equivalent of an ammunition supply.

— Paul Virilio, War and Cinema

War was Roberto Rossellini’s university. Each of his first six completed features, from The White Ship (1941) to Germany Year Zero (1947), details the conditions of total war and its fallout. And if among directors Rossellini possesses an almost unparalleled acuity for the aesthetics of war — rivaled perhaps only by Jean Renoir, a mutual admirer — it is because he cut his teeth under fascism, a political regime under which aesthetics and militarism achieved maximal complicity. No film in Rossellini’s oeuvre displays his mastery at capturing wartime perception more than his fourth film and first masterpiece, Rome, Open City.

Open City (1945) unfolds as a documentario romanzato, a “fictional-documentary” about an episode of surveillance and torture that played out during the Nazi occupation of Rome in 1944. The film baffled early audiences with its newsreel authenticity, frenetic pace, and disorienting sense of hyper-reality. Even the all-knowing James Agee had to see it twice; the second time he declared Open City to be shot-through with “the exalted spirit of actual experience.” Yet behind this first wave of reaction lies a disturbing message. Rossellini offered Romans a re-enactment that many took for documentary: this fact alone suggests that years of surveillance had already come to blur everyday distinctions between life and cinema.

Rome, Open City (1945), dir. Roberto Rossellini

The villain of Open City, Major Bergmann, deals openly in two things: death and images. An image for Bergmann — chief of the Gestapo — is a way to locate and track people, and if Bergmann can find you, he can kill you. Even as Open City begins, the Germans have seized Rome’s networks of communication and vision. Bergmann sees the Eternal City as mere cartography. This is why Rossellini introduces him with an overlay of a map of the city, which he analyzes according to the Schröder Plan, a logistics of divide and conquer. The division of Rome into fourteen sections “will permit dragnet operations on a grand scale with minimum force,” Bergmann boasts while shuffling a deck of photographs. The images he fingers are of resistance fighters in various disguises. “I’m fond of pictures that catch people unaware,” he muses, collecting in one line of dialogue an entire dream of cinema, one that runs from Dziga Vertov through Kracauer’s Theory of Film and into the YouTube prank vid. When the chief of police asks the Major how he knows so much, Bergmann responds, “Every evening I take a long stroll through Rome without leaving this office.”

And so Open City, a veritable ballet of reconnaissance, dances to the music of life under occupation. A once lively street is now noiseless and vacant, now pierced by the alien cadence of a German unit pounding the pavement in lockstep. Everywhere the plainsong of surveillance is met by the barely perceptible rhythms of resistance, of narrow rooftop escapes and back-room exchanges. The hiss of an anti-fascist radio broadcast from London is snuffed out by a closing shutter. A priest launders one million lire for the resistance in the pages of a manuscript. Roman children prepare explosives somewhere out of frame. Everything in Open City is hidden, and yet, somehow, everything is within sight, like the view from a helicopter.

Could it be that modern cinema was born in Major Bergmann’s map room? In a scene shot inside an empty building somewhere along Rome’s Via degli Avignonesi? André Bazin, the critic who situated Open City at the birth of Italian neorealism — and neorealism itself at the threshold of modern cinema — claimed for the film (and its brother, Paisän) the birthright of the image-fait (or fact-image). Rossellini flattens the image, Bazin explains, to the point where everything matters, where no single material or human element outweighs another. Everything visible carries equal density, not unlike the features of a map. That same decade Jean-Luc Godard would locate a sea change in modern cinema precisely at this juncture between occupation and resistance. To do so he would invoke the metaphor of a map: “All roads,” Godard said, “lead to Rome, Open City.”

Rome, Open City (1945), dir. Roberto Rossellini

Yes, but all roads lead away from Open City as well. Many of the same critics and directors who elevated Rossellini’s film to the status of neorealist masterwork were quick to abandon it for higher ground. The problem was simple: years later, Open City didn’t feel real enough. For some, like Gilles Deleuze, the accolades of neorealism were better bestowed on Rossellini’s more “lacunary” follow-ups, like Paisän and Stromboli. Even Godard, in an interview with Youssef Ishaghpour fifty years after his original pronouncement, decamps from Open City. Where he once cited the film as the standard of proof that “art can be consonant with chance” in the face of fascism, Godard now reverses course: “Here too cinema had a second chance but didn’t take it. This is why I quote the example of Rome, Open City. Although it isn’t quite there, although it’s a bit fake.” Godard reprises an oft-heard argument about the film, one that suggests that behind Open City‘s newsreel facade lies not chance but deliberate melodrama, more soap opera than cinema.

And Godard is correct on this point: lots of melodramatic shit happens in Open City. Beautiful women take opium. A mother-to-be is slain on her wedding day. Strong, silent men are reduced to screaming death. Prostitution is implied. A priest beats an oldster over the head with a frying pan. Every principal character, in fact, dies at the hands of the Nazis, in what amounts to not one but three tragedian poses. All of this is a far cry, the argument goes, from neorealism.

Yet, with Open City, Rossellini uses cheating, lying, stealing, and dying — the elements of melodrama — to reveal a new reality defined by surveillance and reconnaissance, occupation and militarism. Somewhere along the way, though, neorealism came to be thought of merely as a naturalistic approach to the quotidian realities of the downtrodden. This led critical perception to favor what Bazin famously called “Zavattini’s Dream,” over and above “populist melodramas” like Open City and its “surprise effects.” Bazin described Zavattini’s Dream as the desire, “to make a whole film out of ninety minutes in the life of a man to whom nothing happens.” The effect of this dream, Bazin declares triumphantly in a review of Umberto D, is to

make cinema the asymptote of reality – but in order that it should ultimately be life itself that becomes spectacle, in order that life might in this perfect mirror be visible poetry, be the self into which film finally changes it.

Rossellini was skeptical of this cinema as a “perfect mirror,” for he knew that cinema, during occupation, had already merged with life, that life had merged with war, and that the reality of war had never really ended at all. He also knew that the Nazis had another name for “watching a man do nothing for ninety minutes”: surveillance. If the goal of realism, for Bazin or anyone else, is Zavattini’s dream, then Rossellini’s Major Bergmann had achieved it long before neorealism became a catchword. The anti-fascist partisans who were consistently photographed without knowing it were Umberto D before Umberto D. Life during occupation, Rossellini proved in the crucial moment, was already life-cum-cinema, because life itself had become spectacle.

Open City can now be understood as one of cinema’s most prescient documentaries about the transformation of one city — Rome, the Eternal City — into the form of cinema itself. (It was made with a hard-to-obtain documentary license granted by the Allied forces.) The occupation of Rome, motored by the divisiveness of Bergmann’s Schröder Plan, turned workaday Romans against each other. Forced into different sectors of their home city, the citizens of Rome were left without a polis, without the basic site required for congregation and civility. Open City shows them pursued and pursuing the city through technology, at a distance from each other. This is why telephones play such a crucial role in the plot of the film. A black telephone, in fact, thwarts the resistance. Rome, during war and occupation, was transformed from a city of actors, a theatre-city, into a city of actor-spectators, of citizens forced to react to the inconstancy of events, the omnipresence of police surveillance, and an enveloping pall of half-truths and disinformation.

It’s possible to trace a family resemblance from the old city symphony films, like Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (1930) and the recently rereleased People on Sunday (1930), right through Open City and into the present. Prior to Open City, the prewar city symphonies were increasingly in thrall to the logistics of speed. Movement in these films is determined almost exclusively by the brakes and accelerations of a city life governed by trains, taxis, and paddle-boats. The portable camera-eye was still a relative novelty. By the emergence of Open City, a new reality had struck, a wartime world where the speed of the motor is merged with the ever-watchful lens of a colonizing force.

Much of the best of contemporary cinema extends this logic. Yet life in the world of modern cinema is not structured so much around foreign occupation as it is the result of what Paul Virilio calls endo-colonization, or the conditions that prevail when a modern nation-state reverse-invades its own population, mostly by undervaluing and under-resourcing its inhabitants. It’s as if the resistance fighters of the global city are strong-armed into a permanent resistance, one marked by ongoing rootlessness and the eventual destruction of all possible abodes, including slums. The dismantling of neighborhoods — à la the Schröder Plan — has accordingly become one of the great features of contemporary film. In Pedro Costa’s landmark Letters from Fontainhas — Ossos (1997), In Vanda’s Room (2000), and Colossal Youth (2005) — the nearly invisible inhabitants of a Portuguese slum dangle in doorways and thresholds that sharply recall Open City‘s Prenestino district. In Jose Luis Guerin’s En Construccion (2000), a neighborhood is cleared away by construction workers who find, to their amusement, that they are “modernizing” a district built on top of a Roman cemetery. (It’s worth noting that this sequence appears to be a direct reference to Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy.) The same raison d’être drives much of the work of Jia Zhangke, Patrick Keiller, and countless others.

Police, Adjective (2009), dir. Corneliu Porumboiu

The contemporary film closest to Open City, the offspring that bears the greatest family resemblance, is Corneliu Porumboiu’s Police, Adjective. Porumboiu’s film shrewdly links the tropes of Slow Cinema — curious longueurs, spectral distances — with a state that spies on its own population. If arthouse cinema in the preceding two decades confirmed the revenge of Zavattini’s Dream, Police, Adjective — picking up where Open City left off — excoriates this tendency. Its long, slow passages of meaningless surveillance are meant to mock a world where states occupy their own populations, and where a complacent cinema falls neatly in line with the order of things. Police, Adjective concludes with a lengthy scene of dialogue in the office of a local police chief, one that immediately conjures up the image of Major Bergmann in his map room. It is in this scene where contemporary cinema most vividly unites the suppressive activity of the police with the destruction of the polis.

The networks of resistance so powerfully articulated in Open City are not lost but intensified in contemporary cinema. On one extreme is Jerzy Skolimowski’s Essential Killing (2010), where a solitary insurgent is chased in a nameless country by an omnipotent American military. On the other extreme is Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers (2010), where a group of masked vagrants roams through parking lots and back alleys in search of temporary communion with waste and detritus. Sadly, both of these films point to a new reality — a neorealism — one where the city, once open, is now an abandoned territory.

]]>