Spatial installation by Snøhetta, music by Arvo Pärt, at 7 World Trade Center. Courtesy of James Wagner.

I’m sitting alone with my MacBook near dusk, listening to a countertenor float eerie lines on a single, high F: “my heart’s in the highlands wherever I roam…my heart’s in the highlands, my heart’s in the highlands…”. The song is on repeat, at a volume as high as I can play it off the half-broken speakers of my five-year-old machine. On September 24 I felt the same Scottish folk song, as arranged by Estonian superstar composer Arvo Pärt, envelop me as I walked into an underground ammunition storage facility. Well over a week has passed between these two moments, and this is the first time I have really been still since then.

September 22-25 marked the final weekend of the second edition of the Guggenheim Museum’s stillspotting nyc, a program of projects from its Architecture and Urban Studies program designed for spaces outside the museum. For this installation, titled/dedicated To a Great City, Pärt, the celebrated and prolific Estonian known for his minimalist, often sacred compositions, partnered with the fashionable Norwegian architectural firm Snøhetta, known most recently in New York for designing the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, to find and create a series of “still spots” in lower Manhattan. Spanning two weekends, the multisite, interactive installation invited ticket holders to experience Pärt’s music in carefully-chosen locations in Lower Manhattan and on Governors Island.

Armed with a map, an identification wristband, a friend and a rare five hours of free time, I set out to experience the Pärt/Snøhetta tribute to New York City almost exactly ten years after the attacks of 2001. I’m curious about how the collaborative process actually went down, because it felt a bit like a high-budget scavenger hunt, the most impressive part of which was access to a couple of beautiful settings otherwise forbidden to the public. Since covering the first installment of stillspotting this spring, I’d been looking forward to seeing what beauty Pärt and Snøhetta could find, or carve out in Lower Manhattan, where I happen to spend a good portion of my time. Through the language of press releases, I’d somehow come to expect an element of live music would be inserted into the curated locations. Unfortunately I was greeted instead by programmed iPod Shuffles and in some settings, speakers (fairly decent) playing recordings of Pärt’s music familiar to anyone who knew his work. I had also read that Snøhetta would “slightly alter” some spaces—with balloons?—but as far as I could tell, the giant white weather balloons I saw in each location, and possibly some mild lighting changes, were the extent of the firm’s preparations. But, hey, they got us into some cool buildings.

What was the definition of a “stillspot” for the collaborators? It’s unclear, but it probably meant a location in or near lower Manhattan that allowed for some rare space for reflection and the virtual suspension of time. According to the official literature, “Listeners become increasingly sensitized as they are drawn in and ideally are transformed to a focused and tranquil state.”

Spatial installation by Snøhetta, music by Arvo Pärt, at the labyrinth at the Battery. Courtesy of James Wagner.

Stillspot number one was the labyrinth in Battery Park, opened by The Battery Conservancy on September 11, 2002 as a means to commemorate and meditate in a traditional Buddhist fashion. The labyrinth is open to all, but on this day a line formed outside of the entrance next to two smiling volunteers who were unwrapping iPod cords and giving estimates on the experience’s duration in time. This was the first of many lines of the day; I quickly learned that waiting, and being at peace with that, was a huge part of the experience, although perhaps unintentional. After chatting with a volunteer for several minutes about the changes on people’s faces between the time they entered and exited the labyrinth (to clarify, the “labyrinth” is a flat, circular path or maze made of grass and stone), I traded my driver’s license for an iPod shuffle set for the beginning of Arvo Pärt’s Silentium, from his 1977 composition, Tabula Rasa, and stepped off.

Looking out at the harbor through the negative space in the Korean War monument barely yards away, listening to this forty-year-old recording of music played by Keith Jarrett, Alfred Schnittke, and other classical stars of the age, all outside motion seemed to stop. I sank into the familiar soothing swells of Pärt’s piece and made my way through the slightly muddy cyclical path, leading to a huge white balloon. I noticed my feet had succumbed to an unusual calm, and I stood looking out at the water. I had removed my bifocals, but a sharp picture emerged. As the music slowed to a nearly silent stillness, each item in the landscape—the water taxi, the seagulls, the tourist child with a balloon, and some grand building across the Hudson came into focus one at a time. I tried to pull my phone out and capture the scene as I saw it, but I knew this was futile from the first fumbling reach into my purse. It was equally impossible to capture a scene of two airplanes flying up West Street, above the right angles of the financial district.

I watched two women going about their headphoned paths along the labyrinth. As the younger of the two neared the balloon that demarcated all installation stillspots, she reached out her hand to the older woman, who took it easily. Thinking they were strangers, my sentimental impulses broke loose and I felt my eyes welling up. I saw them talking familiarly later, but that moment represented something rare nonetheless.

I kept returning to my own “stillspot” within the stillspot, losing myself and forgetting (trying to forget) that I was on display to the line of other ticketholders impatient to find their peace. Once the sixteen minutes of the piece concluded, I removed the headphones, eyes slightly glazed over, and checked a map for the next stop.

Next on the suggested route (the first volunteer I met when picking up the tickets chirped, “you can go whichever way you please but the suggested route is the most efficient!”) were two locations on Governors Island. Having only been to the island once before, for the near apocalyptic vision of hundreds of hungry people stuck on the island for the comically undersupplied food cart festival last fall, I was looking forward to a more pleasant, calming visit. It took over an hour to get there. Moving my way to the ferry through Battery Park, I came across another amazing vision: a full blown pagan festival, complete with a witch lecturing on the subject of doing magic on a budget. I confess I was drawn in by the witches, and I fully include the happenstance as part of my experience with the day-long exhibition. After listening to the speech on using natural elements for Wiccan ceremonies, instead of purchasing the incense and other artifacts that represent these elements (“sometimes less is more,” the redhead imparted to her crowd of about twenty) or purchasing some handmade soaps with spells for each phase of the moon, I pushed through the votaries and the tourists, past the crowd returning to Staten Island, and headed toward the Governors Island ferry dock.

Along the way, hungry, and with ghost pangs from last year’s nourishment shortage on the island, I maneuvered away from barkers offering helicopter rides, funny hats, excursion rides and maps, and stopped at a hot dog stand. This day, defined as it was, I felt I could succumb—if just a little bit—to feeling like a tourist in my own city. After some harsh words with a vendor who could have really used some stillspotting therapy, I consumed a three dollar (three dollars!) hot dog, and waited in another line, the second of several throughout the day. After a good half hour (the first portion of which I spent in the wrong ferry line), I embarked for the two-minute ferry ride to the island. On the ferry, I tried to sit as still as possible, to absorb the surroundings: helicopters, shipping containers and their robotic giraffe lifts, tour ferries, skyline, heavy mist.

Disembarking, my friend and I walked down a path to the left, passed red brick soldier barracks, passed through a small gate and entered what was described as an underground magazine. When I had seen this term on our stillspotting map, I was confused, half expecting the offices of some radical 19th century publication. Then I was reminded that one of the English meanings the French word “magazin” has assumed is that of a safe place to store gunpowder and ammunition. I love that, and will always keep it in mind when reading or writing anything particularly fiery in a periodical. After musing on this for a moment, I was drawn further underground in by an eerie, beautiful sound. There in the dank, misshapen rooms of the magazine floated the requisite white balloon, and the resounding of a countertenor’s voice. Moving from room room to room, I let the sound emanating from corner speakers wash over and around me, my body willingly acting as a conductor and reflector of the disembodied voice in each unique chamber. Throughout my traversal of these spaces, the mournful Scottish song based on an eighteenth-century poem by Robert Burns brought me deeper into a strange, reflective bliss. There were some chairs set up in each cell, and I noticed that a long-haired girl with a book had installed herself in one of the larger storage rooms. I wondered if the security guard who stood near the white balloon all day listening to the countertenor yearn for the highlands was moved to reflection as well. It didn’t appear so.

Spatial installation by Snøhetta at the Magazine at Fort Jay, Governors Island National Monument, music by Arvo Pärt. © Kristopher McKay, courtesy of The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Reluctantly exiting my newfound happy place where I was cheerily examining corner rust spots and peeling paint (I almost had to be literally dragged out by my companion, who reminded me the final ferry was departing fairly shortly), I made my way out of the magazine and back into the light. Moving up an incline and past what looked to be generals’ quarters, we found the next set of volunteers – and the next white balloon – set up at Fort Jay Overlook. Waiting in line yet again, I watched the volunteers fumble with some more iPod cords and try desperately to keep it together. Once it was my turn to experience this spot, I put on the headphones and heard the beginning strains of Mein Weg, Pärt’s more-recently-recorded mimicry of and reflection on New Yorkers’ anxiety. I paced around the edge of the small hill, looking out at the distant city in the late afternoon and, much closer, the voltage boxes that deliver power to Governors Island. I had avoided my phone for most of the day, but now I ducked behind one of the boxes and took a call about an event I was planning that night. Trying to get back into the piece, I put on the headphones, but couldn’t keep my eyes off the growing line of antsy folks awaiting their turn to hear “My Way.” Sometimes, with stillness, one must reflect on one’s own anxiety, but it isn’t easy to take—and it doesn’t feel particularly unusual, or special.

I headed off the island with droves of other people, battling the early fall gnats, standing in another huge line for the last ferry back to Manhattan. On the overcrowded upper deck, I whipped out my notebook and jotted down some reflections, although my elbow was bumped by a fellow passenger with nearly every other line. My partner looked agitated, but graciously waited until we disembarked on the Manhattan side to remind me of a fatal accident some years ago involving an overstuffed Governors Island ferry at the end of the day. With an eye on the map for the next still spot, we boarded the bus which would take us close to our next stop. After getting off we walked through perhaps the least still portion of lower Manhattan. Noisy construction projects had exposed under-the-road-surface pipes and real, centuries-old dirt, with a smell as dank as the magazine. A wave of police cars shuddered past us with their rattling sub-bass sirens. We squeezed through the narrow blue-boarded pedestrian walkways near the new Fulton Street transit center towards the historic Woolworth Building.

Spatial installation by Snøhetta at the Woolworth Building, music by Arvo Pärt. © Kristopher McKay, courtesy of The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Though we were seated in the most grandiose of all the structures I would enter that day, the installation in the Woolworth building lobby turned out to be the greatest overall disappointment. With sore feet, I arrived in front of the famously off-limits doorway to the fabulous gothic-inspired structure that has had the same discouraging gold colored notification installed out front since September, 2001: “No tourists beyond this point.” I waited there for about fifteen minutes, and after briefly story swapping with some stillspotting volunteers I recognized from earlier in the day, I found myself totally ignoring my friend and turning to smartphone land. The hours-long dance of motion and buildup and then just waiting for stillness had proved exhausting, and I retreated into a robotic state, but once inside the lobby, my spirits lifted considerably. Despite the fact that it felt a little gimmicky to be allowed access to this building because of a vaguely-articulated Guggenheim connection, the insanely detailed, golden, stained-glass and marble confection of the early twentieth-century lobby was enough to bring on a momentary unforced stillness, at least long enough to stand and gasp. But that was about it. Our group sat on the grand marble staircase between two white balloons and listened to a prerecorded version of Arvo Pärt’s choral and orchestral composition In Principio on halfway-decent speakers. Given that the maps and brochures touted this portion of the event as “the most theatrical,” I was at least expecting to hear some live music at this junction. The copy from the furnished map reads, describing the piece, “[h]ere dramatic bass sections are relieved by a pulsating rhythm and stoic pace of the choir, representing the balancing act that is common in Lower Manhattan.” Whatever that means, I think I would have gotten a better sense of that “balancing act” had I, first, not been so exhausted and, second, heard a live choir and a live brass section, but maybe I’m being too demanding. After about fifteen minutes when the piece had finished, I got up, had a brief look at the names of the businesses listed in the building directory (mostly law offices), dutifully let my jaw drop a few more times with the wonders of the architecture, and headed out, tired and slightly underwhelmed.

For the final stage of Pärt and Snøhetta’s collaboration, we were allowed access to the 46th floor of 7 World Trade Center. I have to admit that, from the absurdly sleek lobby to the speeding elevator to the pure magic of stepping out into the scene on that high floor of the soaring tower, I was genuinely impressed – and uplifted – this time. A short piano glissando from Pärt’s Hymn to a Great City, with driving notes repeated over and over underneath, filled the inside of the half-finished, unobstructed full floor. It was nearly sunset, and the arts patrons who were there that evening variously stood, sat, or crouched, visibly in awe of the city below. The “installation” unfolded outside through enormous floor-to-ceiling windows arrayed along the edges of the concrete shelf which stretched across from the rough building core in all four directions. There were balloons.

Spatial installation by Snøhetta, music by Arvo Pärt, at 7 World Trade Center. Courtesy of James Wagner.

This is what power feels like, I thought, while nervously staring down the hundreds of feet below, to the Hudson, the financial district, the bridges, and the tangle of streets, buildings and tiny people going about their early evening business. This kind of view is exhilarating, but here it also felt very thin and fragile (I have a fear of great physical heights, so perhaps my own morbid worries took over). I felt the pull of my acrophobia, but I couldn’t ignore the calming beauty of the pink and orange light swallowing the blue and grey below, accompanied by the sound of the driving, glistening piano. At the same time I couldn’t help thinking of the image that I retain most from that September ten years ago, as a thirteen-year-old kid in the Midwest. I saw, over and over on television, people who went to work every day and rode fast elevators and sat looking down on this great anthill jump—in their suits and ties—to their deaths. A screen separated me from that reality and that immense choke of dust which soon followed, but for them, their final moments included the incredible and abominable decision to leap from horror scenes inside onto the unyielding pavements they looked down upon from their mighty offices each day.

Peering almost straight down, one could see the open wounds of the Trade Center’s new reflecting pool memorials, the lighted construction machinery all around them, and in the very midst of it all, Snøhetta’s own soft, bright wedge of a museum. The building has an agenda, it “will provide each visitor with the opportunity to engage in the act of remembering and to ponder the consequences of forgetting.” This portion of the stillspotting experience, too, had a commanding intent. “Amid a blurred landscape of balloons,” the Guggenheim copy reads, “the uplifting tones from the two pianos in ‘Hymn to a Great City’ subtly urge visitors to look forward and beyond.” I read this on the map of the stillspots prior to entering the building, and had decided it was too creepy and so I resolved that I would not be so moved. But I have to admit they were right. I was subtly urged to look forward and beyond, and an excited calm came over me. What I didn’t know at the time was that, just as I was enjoying the sunset with all the calm and stillness and exhilaration I genuinely felt, some #OccupyWallStreet protesters were getting seriously beaten up by the police for an important (and overwhelmingly peaceful) demonstration going on almost directly below me. Stillness and calm are valuable antidotes for New Yorkers, and I am personally and more broadly grateful that the Guggenheim has taken on this largely therapeutic project in our maddeningly loud and excited city. Perhaps however right now is not the appropriate time to be quiet and still.

]]>

Chris Strompolos and Eric Zala, Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Remake, 1981-1989. Behind the scenes, via movies.ign.com

It’s summer 1981. London’s heating up with youth race riots, police forces swarm turbulent areas of Yugoslavia. In its infancy, MTV hits American televisions with music videos starring Blondie, Devo, and Pat Benetar, and ABC’s 20/20 airs the first national television coverage of the “rap phenomenon.” Reagan’s tax cuts dominate American policy debate, and MAD Magazine’s Summer Super Special features fourteen irreverent car and home window stickers. That May, Aljean Harmetz of the New York Times predicted Superman II as that summer’s biggest Hollywood blockbuster. Harmetz was dead wrong: the biggest blockbuster of the summer—and to date at the time—turned out to be Steven Spielberg and George Lucas’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. When Americans were introduced to “Indiana Jones – the new hero from the creators of JAWS and STAR WARS,” they couldn’t get enough.

This was particularly true for two kids in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. Eric Zala, then 11, and Chris Strompolos, then 10, rode the same bus to and from their Baptist day school. They had each seen the film once that summer, and had subsequently bought up all of the comic books, magazine articles, and action figures they could afford on their paperboy salaries. They officially met that fall when Eric borrowed an Indiana Jones comic from Chris one day. Chris invited Eric over to his mother’s house to hang out. This was the beginning of a long friendship for the two. They got to know each other over the course of summer adventures: all-nighters, trespassing, beer drinking, geeking out, and talking about girls. Like all friends, the boys hit their rough patches—Chris, more charming and outgoing than type-A Zala, once took Eric’s girlfriend out for a salad. They didn’t talk for a year. But now, in midlife, they have a solid friendship to look back on. A fairly typical story, right?

There’s a major chunk missing. Let’s revisit the initial meeting: Chris invited Eric over to his mother’s house to hang out. I recall some of my own more inspired play dates resulting in day-long fort building projects, diorama building, plays, even small films. They had nothing on this one; this was a hangout session of epic proportions. Chris and Eric were doing a remake of Raiders of the Lost Ark. [Under the impression that Eric knew a ton about filmmaking, Chris invited him to come over. Under a similarly misinformed impression that Chris had already done the sets, cast the characters, and he could just walk on and help, Eric agreed.] Something about Indiana Jones had struck deep chords in each youngster that summer, and Chris and Eric wanted to re-create their fantasy world on film. As it happens, the boys had something else in common besides their love for Indiana Jones. In Harrison Ford, the boys each found a present, manly role-model to stand in for their absent fathers. In more ways than one, Chris and Eric found a hero in Indiana Jones.

But little did either boy know that Raiders would come to consume their entire adolescence. To be more precise, a harebrained idea transformed into a seven-year film project for the boys. That fall, the boys started drawing up storyboards for the film, largely from memory. This was even before you could rent a VHS of Raiders from Blockbuster, much less illegally download it for free in ten minutes on your laptop. Over the course of their tween and teenage years, from 1982-1989, the two boys remade the entirety of the film, shot for shot. Of course, Chris and Eric didn’t do it all alone. They enlisted fellow Mississippi outcast and classmate Jayson Lamb, who created some truly awe-inspiring makeup and special effects over the course of filming. Just about every kid in the county seat appeared in the film as an extra: either mustachioed, turbaned, equipped with fake guns or sometimes, in the case of Zala’s ten year old brother cutely spicing up the dull “university” scenes with his elbow patched tweed jacket and sprayed-on gray hair. Even the Zala family dog Snickers took a starring role, replacing the allegiance-switching spider monkey from the original film. And Zala’s mom appears in the film credits as “transportation” and is profusely thanked for the use and near destruction of her home.

Thirty years after Raiders (the original) screened, Brooklyn’s Union Docs — a non-profit devoted to non-fiction film exhibition, pedagogy, and discourse — screened Eric Zala and Chris Strompolos’s brilliant, charming, cheer-worthy Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Remake. Part of Northside Film Festival 2011, and screened as a kick-off for Union Docs’ documentary short competition, The Remake was officially out of competition with other documentaries. Which is just as well, as it likely would have blown everything else out of the water. Walking into the tiny space one evening in mid-June, the excitement was palpable. Two humming, white Lasko box fans perched next to two wooden speakers of similar size framed the stage. About thirty squeaky folding chairs and a couple of lightly cushioned side benches quickly filled with diverse enthusiasts clutching their sweaty Miller High Lives. Some even sat on the floor, including New York film commissioner Pat Swinney Kauffman, who arrived with Larry Kaufman mid-screening (in time for a little self-promotion by the latter, who writes on the absurdity of copyright laws and in defense of an expanded creative commons, following the screening).

Union Docs’ programmer Steve Holmgren took the tiny stage, and addressed the assembled crowd. For several years, he explained, he’s been trying to bring Raiders to Brooklyn. He spoke with the unabashed, gleaming pride of a new parent. Next, the “boys” – now in their late thirties, ran up to the stage. Clad in baggy jeans and tennis shoes, the beaming duo thanked the crowd and Union Docs. Chris, who starred in the remake, has grown a thickness of long, black hair since his days—or years, rather—as Indy. “This film consumed our entire childhood,” he remarked. He ensured us that the video we were about to see had been unchanged since 1989, when it was first screened in an old Coca-Cola plant back in Mississippi. Even the original misspelling, “Steven Spielburg,” was left as-is in the opening ode to the film’s creators.

For added authenticity, the film was screened off the original VHS. As Strompolos apologetically promised, the picture and sound quality suffered enormously over the years. Before the film started, a trailer for the documentary Buck and especially some corporate sponsorship from AT&T rudely juxtaposed with the blue screen and DOS-font “audio in” that directly precedes Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Remake. The VHS buzz set in, and an over-serious, almost Biblically inspired scrolling white text on black screen announced the boys’ passion for Lucas, “Spielburg,” and Lawrence Kashdan, the three men “to whom we give our thanks for the work they have wrought which has left a permanent impression upon the direction of our lives.” Indeed.

Then came the film itself. It opens, just like the original, with Indy and his men traipsing through the Peruvian jungle (aka backyard of Eric’s mom’s house in Mississippi). The color is washed out, the costumes undoubtedly began as Boy Scout shirts and slacks, and the “natives” are all blonde. But, by god, the shots looks just like the original. In the spirit of good film geekery, if you watch the clip of the film on You Tube you can read comments like: “pretty cool! But you screwed up where Indy pulls the whip off the log. In the movie he tucks it behind a rock in the wall. That’s how Satipo gets across before him when they are escaping. Besides that, very good job!” Well, I was impressed. When that first shocking dead man covered in blood appears on screen, I was actually amazed by the makeup job. Jayson Lamb, who now works in Hollywood, had some great tricks up his teenage sleeves.

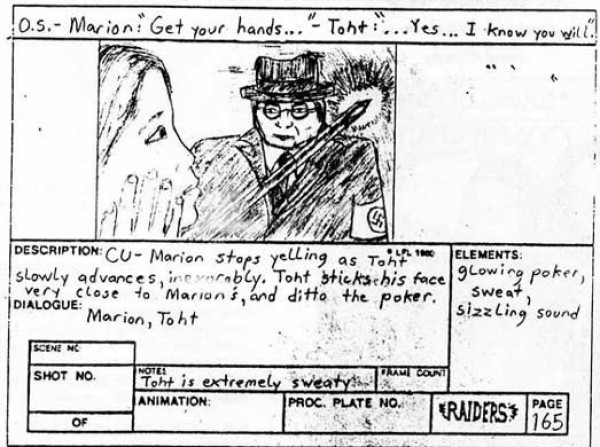

Storyboard for The Remake via TheRaider.net

Chris does a bang-up job as swashbuckling Indy, using all of his teenage might to muster the cool, man’s man 1980s-notsalgiac-for-1930s hero. And soon we meet Zala in a deadpan, villainous Belloq. Chris’s Marion was recruited in a ballsy move—she was older, she was beautiful, she was an acquaintance from church. That she said yes gave Chris more fuel for his Indy swagger.

Due to the poor sound (recorded by Eric’s clunky camcorder, a birthday present) and years of wear, you can barely hear the lines being delivered. But the kids’ acting is so earnest, so decidedly “uncute,” and the effort so complete and impressive that although the final effect is laugh out loud funny, it’s also an undeniably enjoyable piece. When Indy kisses Marion, Chris was having his fist real kiss. When he’s being dragged under a truck, he may have actually been afraid for his life. That truck, however, was not operational. I learned it took 76 shots and two towing vehicles to make the truck move. Many, many highlights exist, not the least of which are watching characters grow up from child to teenager and, on occasion, hearing voices change mid-scene. When the scene changes from the jungle to Indy’s classroom, the pan of students bored at their desks is so believable (because that’s what those kids did for their day jobs) then and so deliciously ’80s (side ponytails, acid wash, scrunchies). And the stop-animated red line over a map showing the progress of Indy’s flight from the states to the jungle, an added DIY bonus.

As the film progressed, I was impressed by a number of details. Eric Zala hadn’t let a single thing go without second consideration. The real Rolls Royce and the plane they used to “travel” back to the jungle must have taken some serious dedication and string-pulling to incorporate into the film, for one. And the first bar scene in Peru was striking for two reasons: those kids were very believable drunks, and the pyrotechnics involved once the Nazis showed up looked seriously risky and actually, quite realistic on film. I later learned that this scene nearly burned down Zala’s mom’s house, temporarily suspending the filming one summer. After a parent conference, the boys were allowed to resume on the condition they had an adult “chaperone” present during filming. According to Zala and Strompolos, the guy picked for the job was “super chill,” (read: stoned) allowing some life-threatening, extremely dedicated experimentation to continue.

The screening audience broke into multiple, spontaneous bursts of applause throughout the entire film. Far more engrossed than I expected, I waited longer than I usually would during a movie to use the restroom for fear of missing a gem. Despite its general bumpiness, its $2,000 budget and the fact that every prop was homemade, it is a quality piece of filmmaking, and the love that drove it into existence shines as bright as the gold spray paint on the ark of the covenant. In this case, even the most “immature” cinema has a totally transcendent quality. Eli Roth, Hollywood producer, recognized this immediately when he got a hold of a bootlegged copy of the tape, passed through several hands since Zala gave a roommate at NYU film school a copy. When the remake screened at Austin, TX’s Butt-Numb-A-Thon film festival, it was an instant success. When Spielberg himself saw a copy, he was committed to tracking the “boys” down and sending them personal letters of gratitude. There’s a reason for the film’s appeal that goes beyond the heartfelt dedication lurking behind every instance of low-budget, high-effort fanaticism. Here is an American story of hero-worship, insane work ethic, and tumultuous family life fueling the obsessive pursuit of boyhood dreams (see the 2004 Vanity Fair feature for the too-good-to-be-fiction details). By the way, Zala and Strompolos recently sold their life rights to Scott Rudin.

In a Q and A session following the film, Chris and Eric (mostly Chris, our Indy) incredulously told their own story. Here were two men in their mid-thirties, still film geeks, still visibly excited and slightly confounded about the work they did as teenagers. They owned up to everything, were delightful, honest, and kind in their responses. I’ve never heard anyone sound so genuinely thankful for their audience. As my crowd streamed out and another one anxiously bottlenecked the single entrance for the ten o’clock screening, I seriously considered staying for round two.

During the talk following the film, someone asked about the giant boulder that chases Indy through the temple of doom. As it turns out, the piece of handiwork took five different manifestations. The first when the boys were twelve and thirteen, respectively. Up all night, they’d gotten bamboo from a nearby swamp, constructed a frame with it, and covered this frame in grey painted cardboard. The boulder looked great at dawn through bleary, blood shot eyes. The guys made one devastating oversight: it wouldn’t fit through Zala’s bedroom door. Next up, a chicken wire structure, this time built outside. A hurricane hit that year, and the chicken wire is still somewhere in the Gulf of Mexico. Not to be defeated, Zala saved up and bought a big weather balloon from the back of a comic book. It arrived, they inflated it, and overnight the thing deflated. Finally they got a local shipbuilder to make a perfect plexiglass ball, convinced some lumberyard workers to deliver two unfinished telephone wire poles to Eric’s mom’s house on a semi.The scene is one of the best-looking in the film, despite/because of the fact that the cave was, like all other indoor scenes, constructed in Eric’s mom’s basement.

The film has been deemed “the ultimate fanboy flick,” but I think it’s much more than that. So earnest a labor of love is rarely found in today’s hordes of remixes, You Tube remakes, spoofs, and recreations. I’m not saying it couldn’t happen now, but the fact that it did when it did, before the internet, before appropriation and remixing became the dominant techniques of cultural production, is precisely what makes it so delightful. For Stromopolos, who needed to be Indiana Jones, and for Zala, who needed to create a fantasy world he could better control, what they made, or rather lived, became an authentic experience. What I saw at UnionDocs was, after all, an entire childhood recorded on VHS. Zala said he still wakes up with nightmares about imperfect scenes, and Chris claimed that it took years to un-train himself to think of every person, car, object, or sound he encountered in the world as a potential ally for their project. Someone in the audience asked about the experience of watching Raiders of the Lost Ark, the original. “When we see the original,” Strompolos laughed, “it’s like seeing a high-budget remake of our film.”

]]>

Rosa Luxemburg addressing the Socialist Congress of 1907. Via barglow

The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg

Edited by Annelies Laschitza, Georg Adler and Peter Hudis

Translated by George Shriver, Verso, 2011

Reading The Letters of Rosa Luxemburg one sometimes feels like a voyeur. Tender love notes are mixed in with daily triumphs and tragedies, accounts of visits with friends, what was for breakfast, nervous missives to one lover written while hiding from another, romantic longings, and multiple self-deprecating jokes about her small stature and ungainly looks. At five hundred and twelve pages, this collection, the most complete available in English, returns the personal struggles of Rosa – often omitted by earlier editors–- to the life of Luxemburg. And somewhere in between hearing of an invigorating walk and watching her curate male affection to assure the publication of her writings, it becomes clear why Verso begins its fourteen-volume complete works of the Polish-born, German revolutionary on such an intimate note: here is a radical portrait for the internet generation. And here’s hoping they pay close attention.

The last letter in the collection is dated January 11, 1919, Berlin—four days before the 47-year-old Luxemberg’s assassination. Born in Poland in 1871, to a middle-class, Jewish family, Luxemburg left to study economics and earn a doctorate in political theory in Switzerland. The first letter in the collection – dated July 1891 – comes just as she is finishing her studies. Among activists, Luxemburg is most renowned for Reform or Revolution, a blistering riposte to the theory of evolutionary socialism then being advanced by Eduard Bernstein. For scholars of Marxist political economy, it is The Accumulation of Capital that is remembered, sometimes as simply a serious contribution to the emerging theory of imperialism, and sometimes as one of the two or three works of political economy deserving mention in the same breath as Marx himself. She was instrumental in the rise of German Social Democrats, and, upon their betrayal at the outset of the Great War, founded, with Karl Liebknect, the Spartacus League, which was to become the German Communist party. It was Liebknect who, without Luxemburg’s knowledge, ordered the ill-advised uprising against the Weimar republic that provided the pretext for their murder at the hands of the paramilitary freikorps under orders from the Social Democratic government. Beyond this, she was a powerful speaker, a natural theorist and editor, and a peer, a friend, and occasional lover to many of the leaders of the international labor and socialist movements: including Leo Jogiches, Karl Kautsky, Liebknect, and Clara Zetkin. For all this, though, it is perhaps her letters for which she is most beloved. Even after several years on the CIA payroll, as compromised a figure as Sidney Hook still had to admit that they were “among the small literary treasures of the century.”

The one hundred ninety letters included in Verso’s volume are drawn almost entirely from the German collection Herzlichst Ihre Rosa, first published in 1990 under the editorial guidance of Luxemburg scholars Annelies Laschitza and Georg Adler. The vast majority of these are addressed to Luxemburg’s long-term lover and political partner, Leo Jogiches and the same is true of the Verso edition. Two decades later, translator George Shriver has consulted some of the Polish and German-language originals to get a better handle on Luxemburg’s multi-lingual style. Shriver’s previous English translations are notable, including Roy Medvedev’s Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism, and Mikhail Gorbachev’s Gorbachev: On my Country and the World. Luxemburg wrote in Polish, German, Russian, and French, often in combination, while sprinkling in English or Latin. Shriver occasionally leaves certain lines in their original form to illustrate the erudite timbre of the prose.

Accompanying an extensive glossary of personal names, abbreviations, and publications, the Verso edition also boasts more letters and footnotes than the German version, these being the only thing remotely dull or academic about the text. In a collection that reproduces, translates, and combines hundreds of hand-written and couriered documents from all across Europe, the editors account for the movement, handling, archiving and storage of the physical pages themselves, which makes for a compelling glimpse into history at work. These letters will give those unfamiliar with their author’s importance valuable insight into her brilliant and unfashionable way of thinking.

For the un-initiated, the Letters, with all their exquisite details, read as well as any novel: we learn how Luxemburg’s Persian cat, Mimi, behaved in the presence of Lenin; how much money she borrowed to keep her numerous publications in the hands of intellectuals and workers; which volumes of German literature she craved; and we hear her pleading with friends to take care of her rent while she was in prison for inciting crowds to riot. Even when some of the details threaten to drag, Luxemburg’s sudden, lyrical moments and proverbial winks at her intended audience suggest thrilling secrets. We feel her grinning, her wrist undulating furiously as her hands fight to keep pace with her thoughts.

Tracking Luxemburg’s relationships with men is fascinating. For Leo Jogiches, initial admiration and respect slowly transforms into frustration at an overly paternal figure. Growing bolder, she chastises him, both for not paying her enough affection and for not giving her enough information about his personal life (she clearly valued telling others about hers). Before things are even over with Jogiches, we find love letters of a more patronizing tone, addressed to Kostya Zetkin. Luxemburg’s terms of endearment switch from “precious gold” for Jogiches to “little boy,” for Zetkin. She wonders if the latter will ever understand economics, and more freely lets her literary tastes dictate his.

One reason why reading hundreds of pages of largely personal correspondence is so invigorating is because Luxemburg’s mind never had a chance to slow with age. Even when complaining of exhaustion, she writes with such energy as to suggest that she never stopped thinking. Her multiple stays in prison become needed respite—quality time spent in cells with other radicals, or alone focusing on her work. Luxemburg’s most celebrated text —The Accumulation of Capital—was written in one season-long sitting, and never saw a second draft. Moreover, she claims to a trusted friend that she wrote it for an audience of one. As Luxemburg wrote of her revelatory economic thesis while imprisoned in 1917:

I know very well, Hånschen [Hans Diefenbach], that my economic works are written as though “for six persons only.” But actually, you know, I write them for only one person: for myself. The time when I was writing the [first] Accumulation of Capital belongs to the happiest of my life. Really I was living as though in euphoria,….Do you know, at that time I wrote the whole 20 signatures [Bogen] all at one go in four months’ time—an unprecedented event!—and without rereading the brouillon [the rough draft], not even once, I sent it off to be printed.

But with Accumulation, as with her letters, there was never an audience of one. Imagining each set of hands that received each set of lines during their century of existence is dizzying. There is first the recipient of Rosa’s warm musings and chilling observations; the jilted lover, say, scouring for terms of endearment; then the bereaved friend seeking comfort and memory after learning of Rosa’s murder; then a committed archivist who would soon find a similar fate in the hands of paramilitary troops; and finally, the scholars, translators, and editors who have provided dates and cities to every party meeting mentioned. And every so often, when Luxemburg references one of her own published works in a letter, we get this footnote: “see full text in the following volume of this series”: a wonderful reminder of how much more is to come.

Personal or political, Rosa Luxemburg’s letters are beautiful, powerful, and succinct. There is also a certain lingering sadness as Rosa could never quite master the exchange of love – the proportions are always off – and her slightly more than occasional longings for a bobo [child] remained unfulfilled.

The editors claim that something of Luxemburg’s role in the intellectual legacy of Marxism can be gleaned from a careful reading of the letters. “Our aim is for this volume,” Hudis states, is

to provide a new vantage point for getting to better know and appreciate Rosa Luxemburg’s distinctive contribution to Marxism. We hope that it will enable us to grasp what she herself consciously struggled to give expression to throughout her life: ‘I want to affect people like a clap of thunder, to inflame their minds not by speechifying but with the breadth of my vision, the strength of my conviction, and the power of my expression’

Yet from this text alone the specificity of Luxemburg’s unique contribution to Marxism remains ambiguous. She often encourages her friends to read Marx and when she speaks of writing Reform or Revolution, she appears a staunch-enough Marxist. Yet in her introduction to J.P. Nettl’s seminal biography, Hannah Arendt questions whether Luxemburg was a really a Marxist at all: “Mr. Nettl rightly states that to [Luxemburg], Marx was no more than ‘the best interpreter of reality of them all… (and) what mattered most in her view was reality, in all its wonderful and all its frightful aspects, even more than revolution itself.”

This seems accurate. Regardless, whatever role Luxemburg actually plays in the history of Marxist thought, it cannot be discerned from reading her Letters. Her view on the role of the intellectual, however, can be. A public intellectual, Luxemburg participated directly in two revolutions, and offered timely, widely publicized commentary on others. She stood at the forefront of political action, siding with the working class, but never abandoning her role as a publisher, editor, writer, and speaker. These were the positions, after all,— that might allow Luxemburg to affect people like a clap of thunder.

In an introduction for the German edition, Laschitza emphasizes Luxemburg’s womanhood, claiming that, “at the same time, through all kinds of difficult situations she remained a woman, with the human strengths and weaknesses and the same problems as any other woman” This is an asinine and offensive statement, meaningless past the point of being patronizing, and, even in a mere twenty-one years, it has aged poorly. One need only substitute any male historical figure to see as much:

“At the same time, through all kinds of difficult situations, [Abraham Lincoln/Vladimir Lenin/Fredrick Douglass] remained a man, with the human strengths and weakness and the same problems as any other man.”

Whatever may be said of Rosa Luxemburg, (Or Lincoln, or Douglass…) it is certainly not the case that she had the same problems, strengths or weaknesses as any other woman, or any other anyone, for that matter. That she didn’t is precisely what makes her so remarkable.

And if editors make perhaps too much of her gender, they do the same for her position as a Polish Jew. These unchangeable facts about Luxemburg—her youth, her expatriate status in Germany, her gender, and her ethnic background certainly make her achievements even more impressive but the implication here comes dangerously close to the kind of “pretty smart for a polish chick,” paternalism that’s best left in 1990. Reading her letters, she rarely stresses her identity or complains about hostility towards her as an independently minded woman, as a Jew, or as a foreigner in Berlin. Instead, she focuses on ideas and celebrates life. Let us remember Luxemburg for rising above the pig-headedness of her fellow radicals, certainly, but if we read her own, candid words carefully, we find plenty to celebrate strictly in what she had to say and how she said it.

All that aside, I wholeheartedly agree with the editors’ that this collection will intensify the reader’s appreciation of Luxemburg as a writer and as a historical figure. This volume does not lend any landmark insight into Luxemburg’s political thought, nor does it stand alone as a triumph of feminism. What it does instead is provide an essential portrait of a committed intellectual.

This year, revolutionary action dominates world news. American media overwhelming characterize demonstrations in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, Libya and Morocco (the list will undoubtedly expand in coming days), as youth revolts. The most attractive point of comparison between recent demonstrations to oust dictatorial leaders and/or spark political reforms may be the youngness of the protesting masses. However, members of the working class— not just “young people” in general — are spearheading the current political motion. The revolutions we are witnessing today have thus far been leaderless—something Rosa, wary at the turn of the 20th century of the rise totalitarian power, would have likely approved of.

Thus far, we have not witnessed Luxemburg’s rhetoric surfacing in protest literature, but perhaps that will change with Verso’s massive release of Luxemburgism in the coming years. In 1966, Hannah Arendt mused, “[o]ne would like to believe that there is still hope for a belated recognition of who she was and what she did, as one would like to hope that she will finally find her place in the education of political scientists in the countries of the West. For Mr. Nettl is right: ‘Her ideas belong wherever the history of political ideas is seriously taught.’”

Arendt would be overjoyed with the news of Verso’s undertaking to reintroduce Rosa Luxemburg to the canon of radical thought—as should we all.