Christopher Williams, Garten in Voigtmichelshof, Alpirsbach June 7th, 2010, 2010. Via David Zwirner

Highly polished visuals appear commercial in their flawlessness. Sincerity becomes increasingly hard to perceive against the context of advertising, of mass demographics, of no context. Efforts to represent truth become local and hopelessly baroque. In the rare moments when they appear unexpectedly, traces of order or exertion are immediately suspicious. Avoiding compromise, appeasement or untoward collaboration is not only an artist’s full time job, but a life’s work; still, the photos that line the walls at David Zwirner are a bit too realistic for comfort.

Christopher Williams titled his show For Example: Eighteen Lectures on Industrial Society. But although we’ve been prepared for instruction, we don’t find it forthcoming. Connotations are stretched to meet one another like a game of Pictionary in the space between photos. Dry cleaners, apples, dark room supplies, a Miro sculpture: his various symbols model for one another within their expanded system.

Christopher Williams, For Example: Dix Huit Leçons Sur La Société Industrielle (Revision 12), 2010. Installation view via David Zwirner

Williams’ work isn’t difficult, it’s just a bit harder. His is the shiny difficulty of runway conceptualism. Production value is one obstacle; lengthy and detailed captions that accompany each photo are another. These last operate in pointed excess of the purpose Benjamin set for them:

“Captions must begin to function, captions which understand the photography, which turns all the relations of life into literature, and without which all photographic construction must remain bound in coincidences.”

Rather than turn relations of life into literature, the title of the image of a camera cutaway, Camera: Praktika, Praktisix (1959-64), Kamera- und Kinowerke Dresden, 120 film 6×6 cm, height: 11 cm, width: 16.5 cm, depth: 12 cm, weight: 1280 g, Lens: Carl-Zeiss-Jena, Tessar 1:2,8 80mm, normal lens: Biometar 80/2.8, lens mount: Praktisix Bayonet, typical serial no: 20830 aims to turn them into matters of industrial precision. Both the enthusiasm of the images and the captions’ semiotic austerity are ambitious in similarly antiquated ways. By deflecting us back onto the image a second time, the caption rehearses the eclipse of literature; its space filled with a stream of instrumental measurements. This unavailability complicates the appeal of the image, leaving it bound, as it were, in coincidences. Both aspects of the work aim to impress us with their insensitivity: the artless polish of the images offends our taste while the captions’ conceptual commitment wears us out. When their marriage comes into focus the room begins to feel claustrophobic.

Weimar Lux CDS, VEB Feingerätewerk Weimar, Price 86,50 Mark GDR Filmempfindlichkeitsbereich 9 bis 45 DIN und 6 bis 25000 ASA, Blendenskala 0,5 bis 45, Zeitskala 1/4000 Sekunde bis 8 Stunden, ca. 1980, Modells: Ellena Borho and Cristoph Boland, is an alluring image of a light meter before an out-of-focus woman sprawled in a green dress. Williams writes:

To focus is to assert a preference for one surface over another. To choose between the light meter or the green dress. How to represent them? Let’s say that both, on that afternoon, trembled slightly.

Here the original function of the caption is relocated to the press release. Each model’s name becomes one possible setting among others, and the image is a serving suggestion.

Christopher Williams, Weimar Lux CDS, VEB Feingerätewerk Weimar, Price 86,50 Mark GDR Filmempfindlichkeitsbereich 9 bis 45 DIN und 6 bis 25000 ASA, Blendenskala 0,5 bis 45, Zeitskala 1/4000 Sekunde bis 8 Stunden, ca. 1980 Modells: Ellena Borho and Cristoph Boland November 12th, 2010 2010. Via David Zwirner

Less obvious connotations emerge in the photos without explicative mini-texts. Industrial eco-systems lurk in images ostensibly depicting individual or naturalistic simplicity. In Bergische Bauernscheune, Junkersholz, Leichlingen apples are captured in a state of perfection moments before they’re picked, crated, and distributed. A rolled bale of hay in Naturpark Schwarzwald Mitte/Nord neben Bergach gestures at an unseen process. Even the image of a mop leaning on an office wall, Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, Lichtentaler Allee 8a, Baden-Baden, Germany, invokes a broader system.

While reading the press release, I noticed Williams’ inclusion of lyrics from the Canned Heat song, ‘Going up the Country’. The song is a romantic vision of escaping to the countryside, and it is jolly and buoyant in its irony and its cynicism.

Garten in Voigtmichelshof, Alpirsbach, an image of fragile green leaves shimmering in the sunlight was perplexing in its simplicity. Perhaps there is an echo of industry rumbling in the background, I thought; but instead of harvesting, preparing, or packaging the subject of the image, the echo just dances around it. Unlike the apples, these leaves will simply fall to the ground when the seasons shift. At this point I was performing my own act of extraction. Rather than allowing the leaves to exist pleasantly in isolation, I was mining them for significance.

Christopher Williams, Bergische Bauernscheune, Junkersholz, Leichlingen September 29th, 2009, 2010. Via David Zwirner

So I returned to the press release. Gradually, the echo of industry was drowned out as the leaves started singing, “I’m going up the country, babe don’t you wanna go… I’m gonna leave this city, got to get away…” I felt Williams exude a sigh of relief, soothing my ambition to engage and I tapped my foot to the naive jubilation of Canned Heat.

]]>

Bruce Conner, Valse Triste, 1977. via Fine Arts LA

The language of the visual world is both internal and external, simultaneously ignored and unconsciously absorbed. In rare instances its manipulation enables us to perceive it and to take part in the conversation. The mind works incessantly, constantly consuming images, with little respite to meditate on the well of rapidly accruing connotations. On those occasions when the vocabulary is revealed, we can consider how these associations relate to one another and delineate our perception; an almost spiritual introspection of our visual databank and an opening for active participation in the visual dialogue.

When Bruce Conner passed away in 2008 at the age of 74, his legacy, like his work, was not a simple one to decipher. His was a multifaceted career piloted by an ardent skepticism. Where he mistrusted words, he worked with images. When his style was commended, he changed it. When the commercial art world accepted him, he faked his death (his first solo show was titled, “The Work of the Late Bruce Conner”). He was dubious of institutions, terminated his career more than once, withdrew his films from distribution and often sent proxies to play ‘Bruce Conner’ at panels or screenings. When it came time to memorialize the protean Conner, he was canonized for his work in sculpture, collage and assemblage, but it was his experimentation with the moving image that won him overwhelming tribute and lingers as his most relevant work.

Conner first garnered attention for his assemblages in the late-1950s. The mysterious clusters of forgotten material (wood scrap, torn nylons and trashy magazines were signatures) thrived on a tension between the distinct and the entire. Hidden symbols or objects, perhaps enmeshed by nylon or encased in wax, kept works alive by tempting viewers to scrutinize their surface. The hidden is both obstructed, yet imbued with the energetic compulsion to be revealed.

Bruce Conner, Crossroads, 1976. via impakt

Eventually, Conner grew apathetic of amassing praise for his assemblage work and returned to an early love of cinema. In 1958, friend and filmmaker Larry Jordan taught Conner how to splice film. Unable to afford a camera or film stock, he salvaged several hundred feet of “used” newsreel, instructional film, commercial stock and narrative features at a photography shop. What came of those reels thrust him deeper into the art-world limelight and made a lasting impact on American experimental film.

Throughout Conner’s childhood he digested the vocabulary of popular cinema at the McPherson, Kansas movie theater, fashioning a lexicon he carried into adulthood. What most interested him, then and later, were the structures and devices unconsciously received by audiences. From an early age Conner recognized in the methodical editing, recycled footage and repetitive narratives a persistent structure of feature films. Seduced by this secret dialogue across seemingly distinct works, Conner made it the focus of his own.

A Movie, from 1958, was Conner’s first film and an attempt to create the “anti-movie.” In 12 minutes of images and sound he finds enigmas, impetus and consequence, summoning the structure of conventional film making to the foreground and challenging the accepted method of reception. The initial swell of a cinematic soundtrack engenders our expectations, but is accompanied by 30-seconds of the static title ‘Bruce Conner’. Two minutes in, Conner has already demarcated the elements of narrative cinema by rearranging title sequences, countdown leader and end credits interspersed with footage of a sexy strip tease. The remainder of the film is a series of hilarious, bizarre and often horrific visual puns and juxtapositions. Nude women, explosions, war footage, dare devils, plane crashes and Hollywood chase scenes are woven in a swift, kinetic cadence and set to a dramatic soundtrack. The most obvious Hollywood tropes are present but arranged to expose their edges; they appear arbitrary here to highlight the intention behind their arrival everywhere else.

Bruce Conner, A Movie, 1958. via kunst der vermittlung

While not the first to use found-footage, Conner’s total commitment to it was new, and the results were in many ways more potent than anything previously seen. Following the energetic rhythms of A Movie, Conner continued making films from his growing library of found images. In 1967 he completed his seventh film, Report, concerning the media representation of the JFK assassination. The film first illustrates, then critiques, the overabundance of coverage and the collective obsession with following it. Walter Cronkite’s famous report guides the audience as we are escorted through the events of November 3, 1963 via repetition of the assassination footage, flickering screens, television advertisements, bull fights and movie clips from Frankenstein. If the media-as- Frankenstein’s-Monster conceit feels a bit dated it is only because it has become one of the organizing principles of contemporary production, endlessly translated, compulsively reiterated. It is a credit to Conner that he can thus be read as a Frankenstein of our own, as his pop-cultural assemblage, animated and baleful, continues to stalk the realm; an undead form persisting past the point of critical efficacy.

Released during the long ascent of Pop Art, Conner’s films offered an alternative vision of the visual commodity and image culture. As opposed to the bright, tonic imagery characteristic of the genre, Conner drew from the decayed and cheerless, relying on the insignificance of his acquired reels. His films seem stained by history, implying a darker ‘anti-pop’. He once elaborated, “I get impassioned and that’s not cool and cool was what pop art was all about.”

Conner’s early, fast-paced films are set off by their refusal to let audiences see through the screen. In laying bare the tropes of orthodox film making, he reminds us of the film’s physicality, rooting viewers in their seats. Uprooted images and empty screens make typical, unconscious absorption impossible. Viewing these films today begs the question of what a similarly materialist ruthlessness would look like for our own time. Not only is film itself no longer physical in the same way, but its not clear that the same sort of passive image-ingestion is at work in the digital age; we are instead presented with new structures, new products. To watch Conner’s early work is to feel a twinge of melancholy; a longing not only for his uncompromising clarity, but for its availability as a position.

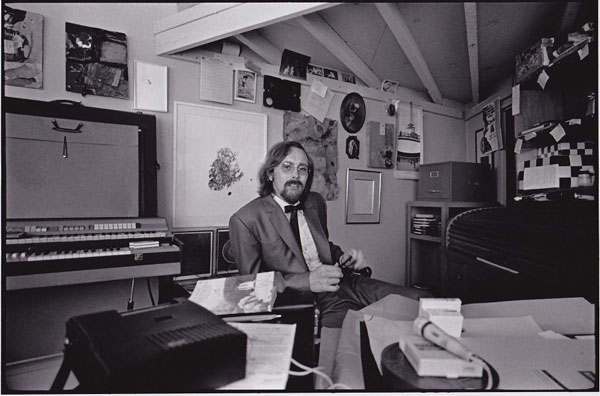

Bruce Conner, via Anthology Film Archives. Photo by Robert Haller

By the 1970s, other filmmakers had began working in Conner’s style and he lost interest, pursuing a radically different approach in three of his most famous works, Crossroads, Valse Triste and Take the 5:10 to Dreamland. These films, propelled by gentle, ambient soundtracks, abandoned the visually arresting, rapid-fire editing of his earlier works. Crossroads is a 36-minute montage of slowly shifting mushroom clouds cobbled from Defense Department footage of nuclear testing. Through 27 different takes of the tests, Conner edits a film of inharmonious emotions, creating a visual ode to an ultimately destructive power, tempting us with the beauty of its aftermath. Valse Triste and Take the 5:10 to Dreamland unveil a more meditative style. Simple and elusive in their nature, both invoke a dream-like state, providing a metaphor for reflective experience. Take the 5:10 to Dreamland weaves an ambiguously unstructured series of images, coincidental and meandering. While his early films highlighted the confines of the medium, 5:10 refuses it outright, denying the existence of a cinematic boundary. Valse Triste follows a similar pattern but with autobiographical undertones of a Kansas boyhood dream.

In 1978 Conner returned, in a way, to the spirit of his earlier interventions with Mongoloid, set to Devo’s song of the same name. Long before MTV, Conner produced a rhythmically and intellectually resonant relationship between music and the moving image. Mongoloid combines educational science videos, film clips and television advertisements to tell the story of a boy who conquers a mental disability to become a useful, even ideal, man. This film, along with his work for Brian Eno and David Byrne (Mea Culpa and America is Waiting) are the star witnesses in the case for Conner’s fathering of the music video. It is a vigorously contested paternity. Presented with the title, the artist, in a phrase doubly delightful for its reciprocal implications “demands a DNA test.”

![Conner_Jackie[0]](http://idiommag.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Conner_Jackie0-e1289465023731.jpg)

Bruce Conner, Report, 1963-67. via museum joanneum

Conner’s contributions to film are, in very real sense, undeniable. Since his early explorations, sampling and remixing have become mainstream, even traditional, in film and video. In unearthing a common cinematic and visual language, he charged the use of pre-existing and discarded imagery with an emotional and political power whose influence cannot be overstated. So long as repetition, saturation, and vapidity continue to characterize the lived experience of the moving image, the devastating simplicity of Conner’s deconstruction, de-contextualization and re-materialization will retain its urgency. No two viewings of a Conner film are the same, for as images relentlessly sediment the edges of our consciousness, his work persists in drawing our attention to the latest elsewhere of the everyday. New associations are made and new possibilities opened. Conner’s films are an enigmatic cancer of visual exchange, growing more vital with each encounter.

Still, his moment is not our own, and though this fact is often brandished to wish away the ghosts of didactics past, it is, itself, an opening. Just as coral reefs are so many skeletons, appearing only as a certain life departs, so too the form of art, its architecture, emerges only when its temporal surface turns to dust, burns off, and vanishes in the shifting wind. And so the audacity of Conner’s work takes place a second time, as it debuts its bones. That these are so familiar is to signal their significance, as evidence in the archive of our becoming.

In an interview with William C. Wees, Conner said, “I’ve always known that I was outside the main, mercantile stream. I have been placed in an environment that would have its name changed now and again: avant-garde film, experimental film, independent film etc. I have tried to create film work so that it is capable of communicating to people outside of a limited dialogue within an esoteric, avant-garde or a cultish social form. Jargon I don’t like.” Conner created a kaleidoscopic vision that interacts with any who agree to watch. A refreshing take on the sometimes cryptic genre of the ‘experimental’, his films are inviting, humorous, emotionally legible and dramatically charged. Literally written in a language everyone can understand, they can be superficially enjoyable or effectively inexhaustible. They offer as much as you want to take.

Film Forum presents: ‘Bruce Conner: The Art of Montage’, November 10-23

]]>

Danh Vo, Autoerotic Asphyxiation, 2010. Via the author.

Upon exiting the elevator at Artists Space, viewers encounter a nearly vacant gallery. The colorless room is alight with the glow of sun caught in white curtains lining the windows. The unexpected emptiness is both comforting and unsettling. There is something beguiling in all that absence, as if the room is asking for our careful attention.

Elegiac in their preoccupying calm, the images and objects inhabiting Autoerotic Asphyxiation coyly recall the past, fashioning a peculiar nostalgia. Danh Vo, born in Vietnam in 1975, has created an environment which asks viewers to take an active role in exploring the histories behind the assembled relics. At the age of four, Vo and his family fled the Communist victory in Southern Vietnam. Hoping to reach American shores in a boat built by Vo’s father, they instead encountered a Danish shipping vessel, and, upon arriving in Denmark, were granted citizenship. Vo grew up in Europe, irresolute over his cultural identity, as his recollections of Vietnam became increasingly distant. Much of Vo’s work has been consumed by mining the abandoned trajectories, escaped identities and forgotten pasts that make up the enigma of his origins.

In recent years, Vo’s practice has emphasized appropriated items that question ideas of ownership and identity. Works have included the marker of his grandmother’s temporary grave – her name written in the Latin alphabet – as well as legal marriage documents lengthening his own name and three items coveted by his father in Vietnam but only attained in the West: a Rolex, a Dupont lighter and an American military class ring. Though these objects cite a personal history, they become detached as they interact with audiences and with one another, creating a kind of updated dialogue. Vo presents dismantled fragments of his own past to remind us that memory is a vestigial collection, perpetually reassembled, of which we are only a product or effect.

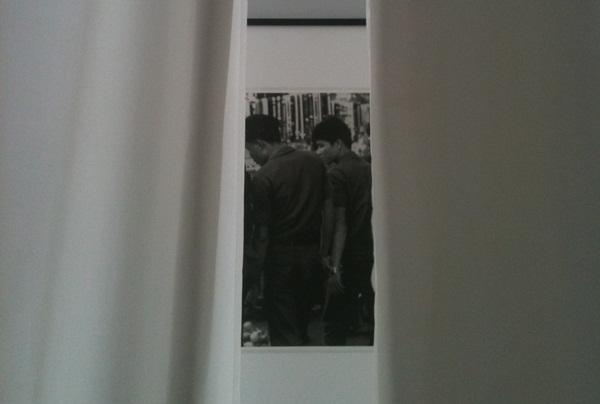

Danh Vo, Autoerotic Asphyxiation, 2010. Via Artists Space

At Artists Space, Vo further pursues these themes with objects, photographs and documents that elicit a spirit of inquiry. The most immediately visible works in the room – the sheer curtains concealing both windows and walls – reveal, upon closer inspection, flowers embroidered in some of the fabric. These, in turn, are all species discovered throughout China and Tibet by French missionary and botanist Jean-Andre Soulie, who exported them to Europe. In 1905, Soulie was tortured and killed by Tibetan monks, though his memory remains embedded in his flowers’ Latin titles, crediting him with their existence.

Concealed behind the fabrics and tucked between windows are several sets of black and white photographs of Vietnamese men and boys. The intimate pictures exude an air of homoeroticism and evidence a keen fascination with masculine relationships in Vietnam. Images of men working or eating are accompanied by photos of men holding hands and embracing. Moving through the gallery becomes an active search as one parts the curtains along each wall to locate the photographs. The act of displacing a physical partition rehearses the artists’ process while foregrounding the division between audience and photographer, past and present.

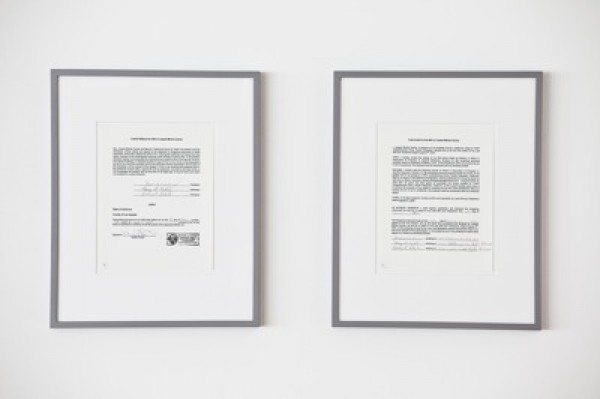

Accompanying the photographs are two framed documents which make up a codicil signed by Joseph M. Carrier and Danh Vo. The will grants ownership of Carrier’s possessions, including the photographs, to the artist. Employed by the RAND Corporation in Vietnam from 1962-1973 and, as a gay man from America, Carrier was fascinated by the alternative presented by Vietnamese culture. Struck by the outward affection between men, Carrier documented the behavior with his camera. In the series, the war is a dim, even coincidental, backdrop. It appears in only one of the photos, as a distant, hazy bomb cloud observed by a line of bathing boys in the foreground. Carrier was fired after nine years in Vietnam over suspicion of homosexual activities which RAND considered a security threat.

Danh Vo, Autoerotic Asphyxiation, 2010. Via Artists Space

Carrier’s fascination continued into his later life and illuminates his relationship with Vo, which led to the excavation of the photographs. The images, captured in the decade when Vo was living in Vietnam, provide a survey of this undocumented and forgotten period in his life. The legal documents become an appendage to his identity, physical evidence of his own reconstruction of the past. The lives and scenes captured by Carrier grant Vo the remains of a personal story with which to construct an autobiography.

02.02.1861 conjures a similar exchange, albeit in the opposite direction. The piece is a handwritten copy of a letter from Saint Theophane Venard reproduced by Phung Vo, the artist’s father. Theophane Venard was a priest with the Paris Foreign Missions Society who moved to Vietnam in 1852, when it was illegal to proselytize in the country. Confronted by authorities, Venard refused to stop his ministry and was taken into custody. Shackled in a cave, he spent three months writing letters to his family and friends as he awaited execution. His correspondence expresses no remorse for his actions or fear of death, as he instead anticipates martyrdom with excitement and unshaken faith. The letter copied by Phung Vo was Venard’s last and was written to his father. He writes: “a light blow of the saber will separate my head as a spring flower that the master of the garden gathers for his pleasure. We all are a flowers on earth that god picks up when the time arrives, earlier for some, later for others.” In interviews, Vo has expressed a sympathy for the French missionaries and their well-meaning, if quixotic, beliefs.

Danh Vo, Will, 2008. Via Artists Space

Venard’s glorification of his own death is set against the exhibition’s accompanying text, printed on a metal plate near the letter. An excerpt from the ‘Department of Correction, State of Delaware: Execution by Hanging, Operation and Instruction Manual’, it details the standardized process for preparing the gallows in startlingly systematic language. Describing a procedure in stark contrast to Venard’s euphoric expectation, the tension between the two centers our attention on the interaction of the priest’s identity and the reality of his fate. An imminent beheading, filtered through the idiom of individual history, becomes a revelation.

Near the letter is a photograph of Venard and other missionaries as they are leaving Paris in September of 1852, along with a passport photo of Vo taken in 1980, upon his arrival in Denmark. This photograph of a vulnerable young Vo brings the room, and the show’s title, into focus. The image of ‘autoertotic asphyxiation’ is that of a life snuffed out through repeated attempts at summoning an identity held hopelessly in reserve, a literally terminal self-fascination. As a title, the term offers a winking apology for the same. In the latter case, Vo needn’t have worried. His exhibition invites us in, offering a deft, intimate portrait of the provisioning of memory into self. In choreographing his own nonlinear past, Vo reminds us that though history is made of sedimentary traces, its trajectory is our own creation.

]]>