…graves at my command

Have waked their sleepers, oped, and let ‘em forth

By my so potent art.

— Prospero; The Tempest Act V Scene 1

An Irish ballad written in the mid-nineteenth century tells the story of a drunk named Tim Finnegan, who was taken for dead after falling from a ladder in an alcoholic daze:

[They] laid him out upon the bed

With a bottle of whiskey at his feet

And a barrel of porter at his head.

When his mourners get to drinking, the wake devolves into a town-wide brawl: “woman to woman and man to man.” Eventually a flying whiskey bottle shatters just above Tim’s corpse and, drenching him, revives him from death:

Timothy rising from the bed,

Sayin’: “Whittle your whiskey around like blazes!

Thanam o’n Dhoul! D’ye think I’m dead?”

In the silent-film re-enactments of “Finnegan’s Wake” that bookend Hollis Frampton’s 1979 short Gloria!, the ballad’s story plays out in broad, puppet-like gestures: dancing, weeping, fighting, limb-flailing. When Tim wakes near the end of the final clip, he waves his arms around like a boogeyman and sends his well-wishers scattering away. Left nearly alone in the frame, he kicks the last mourner out the door, raises his fists to the ceiling and leaps around triumphantly, clutching a bottle in one hand and a club in the other. These clips bookend two longer episodes. On a solid green screen, scrolling digital text spells out a series of sixteen “propositions” about Frampton’s maternal grandmother—including that “she remembered, to the last, a tune played at her wedding party by two young Irish coalminers who had brought guitar and pipes.” We then hear, against a now-empty green screen, that same tune played from start to finish.

Gloria! was the last completed component of an intended thirty-six-hour-long film cycle inspired by the travels of Magellan, whose literal attempt to “encompass all human experience,” as Frampton once put it, corresponded to the director’s own compulsion to leave no subject unfilmed, no technique untried, no medium unexplored. The film found Frampton looking forward in multiple senses: eagerly adopting new technology (digital interfaces; computer-generated text) and frankly anticipating his own death. At the same time, Frampton’s circumnavigation of human experience ended up taking him back to his earliest childhood memories, his family history, and the origins of cinema itself. Gloria! begins and ends with a resurrection: a moment when, there being no more future to anticipate, life rewinds itself and begins again.

How is it possible, Frampton seems to be asking, to organize something as elusive and circuitous as memory into sequential thoughts? Frampton’s attitude toward remembrance in Gloria! is almost mathematical, as if the past were a series of facts to be manipulated and derived. At the same time, he’s careful to distinguish between the mushy, vague language with which we often talk about memory and the ambiguities built into memory itself: “these propositions are offered numerically,” reads the first line of onscreen text, typed out in start-stop keyboard rhythms, “in the order in which they presented themselves to me; and also alphabetically, according to the present state of my belief.” The structure(s) of Gloria! are meant to account in equal measure for time as it exists in the abstract—a linear, unbroken, one-way progression of minutes, seconds, and hours—and for time as it’s actually experienced by those subject to it: jumbled, overlapping, doubling back. The tension between these two competing structures is, Frampton suggests, essential to the logic of memory, where every moment exists in theory as a single, unrepeatable entry in a linear sequence, and in practice as something stickier, more resonant, available to be savored and returned to at length.

It’s also, by extension, the logic of the movies, which remind us of the temporal distance separating us from their subjects even as they make the past seem like something tangible and close. It’s possible for us to be so swept away by this second illusion that we forget the fact that precedes it; so taken with a film as it plays itself out in the present, our present, that we overlook its essential point of origin in the past. Occasionally, a cut will cue us into the illusion, remind us that the footage we’re watching isn’t so much a natural emanation of the present as a re-animated, re-assembled product of the past, stitched together from moments of dead time. I’m thinking, for instance, of the abrupt leap in Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln from a springtime courtship to a graveside vigil, or the cut late in Ozu’s Late Spring that displaces a moment of father-daughter tenderness in favor of the daughter’s marriage to an unseen and unloved groom. There is something cruel, final, and decisive about these cuts; they are about the impossibility of clinging to the present and the equal impossibility of returning to the past. Just as Lincoln can never revive his beloved, we can never return to that moment when a young Henry Fonda stooped by a studio-built grave at the behest of a pre-Searchers, pre-war John Ford.

The computer-generated text that occupies much of Gloria! deals in concrete, vivid details: we learn that Frampton’s grandmother kept pigs in the house, though never more than one at a time; that she hailed from Tyson County, West Virginia; that she was obese; that she taught her grandson to read; that she “gave him her teeth, when she had them pulled, to play with”; that she gave birth to nine children, four of whom survived (all daughters); that she was married on Christmas Day at age 13; that, when the filmmaker-to-be was three years old, she read him The Tempest. And yet these bursts of digitized text, even as they point toward a specific point in time, keep that point at a threefold remove: by the time we encounter that woman reading Shakespeare to her toddler grandson, the scene has been filtered through Frampton’s imperfect memory, abstracted into a series of words and phrases, and digitally rendered by a process that further abstracts those words and phrases into streams of numerical data. With Gloria!, Frampton was anticipating a time when information about the physical, time-bound world would be stored outside that world, in an immaterial digital space made up not of ink, matter, or sound waves but digits and pixels. But he was also, I think, encouraging us to consider that scene between grandmother and child as if it existed independently of any one set of digits, pixels, letters, words, or grains, in a space outside of time. The paradox, he suggests, is that such a space—if it did exist—would only ever be accessible to us through a material, time-bound medium.

Shakespeare critics have often taken Prospero’s abjuration of his magic near the end of The Tempest for the Bard’s own thinly-veiled farewell to the stage. If it is a goodbye, though, it’s also a kind of celebration. On Prospero’s part, it’s a statement of faith in the power of the wizard’s art to provoke storms, dim the sun and raise the dead (sixteen centuries after Lazarus and two before Finnegan). And on Shakespeare’s part, it’s a statement of faith in the power of words—if not to resurrect the dead, then at least to call forth their ghosts. The autobiography in Gloria! is both more explicit than that of The Tempest and subject to more layers of ironic distance. Even Frampton’s coming-to-terms with the idea of autobiography is winkingly impersonal: “she convinced me, gradually, that the first-person singular pronoun was, after all, grammatically feasible.” But no amount of tongue-in-cheek detachment or digitally-imposed distance could conceal the flesh-and-blood woman at the film’s center, who once scolded her three-year-old grandson for liking Caliban best out of all the cast of The Tempest, and who lives on in a space where time-bound images blur into computerized text: a brave new world that may or may not also be a world long gone.

]]>

“Lukas, in the middle of the film, the actress will pay a visit. You’ll fall in love with her. And you’ll understand your father. I’ll become your memory. I haven’t shown you the middle yet.”

The words are spoken by a female voice over a black screen at the start of Lukas the Strange (2013). They make a promise while longing for a connection. It’s unclear who both this woman and Lukas are, though she leaves the sense that whatever distance exists between them will be difficult to breach. As the film continues, the voice promises to tell more about what happened—why a man left his family, why a woman grew so sad, and what was in the box that she threw into the “river of forgetting” that encircles the village. “These are things that need telling,” she says out loud, and then wonders, “But how can I tell Lukas without him forgetting?”

In all of the Filipino filmmaker John Torres’ films, stories exist to fill a void that lost memories have left, and throughout them all, the fear lingers that the void will remain. For the rural community in which his fourth feature film unfolds, a void exists in the form of an actress who’s disappeared from the film shoot underway there; for Lukas, a void also exists in the form of his father, who tells the 13 year-old, “Son, I am a tikbalang” before abandoning him. A tikbalang is a creature from Filipino folklore—half-man, half-horse. Lukas goes on to wonder whether he himself will grow up to be one then, as he dons a helmet to play a tikbalang in his town’s film shoot and casts himself in the image of a departed loved one.

Torres (who was born in Manila in 1975) had previously recalled lost loved ones in his second feature, Years When I Was a Child Outside (2008), which recreated his experience of having been separated from his father when he was young. Actors present a version of his family history, with Torres himself narrating from offscreen to “You,” creating the impression of a man reaching out to his younger self. This differed from how Torres had told his own story in the first-person in three early shorts that the critic Alexis Tioseco collectively labeled the “Love Films,” which circled around a longtime love relationship’s end. Yet even though their modes of address differed, the films shared the same impulse: to ease pain through storytelling.

Lukas the Strange, which received its world premiere at this year’s International Film Festival Rotterdam, also does this. Lukas is not just the first film work by an artist who has previously shot exclusively in video, but an overtly retrograde film in its recollection of earlier tales. Early on, brief deteriorated images appear of a young woman walking past villagers, including a young boy. These images, taken from the director Ishmael Bernal’s 1974 film My Husband, Your Lover, offer a prelude to a new work made with the grainy, occasionally flaring visuals and dubbed sound of Filipino films from the 1970s and 1980s. In drawing on this period, Lukas the Strange also invokes the years of the Philippines’ military dictatorship, during which a number of political dissidents were murdered before the military gave way in 1986 to corrupt, neocolonial democracy. As Lukas reenacts the role of his father, the present calls upon memory to help it fight absence and silence; at the same time, the film suggests the pain of remembering to be so great that some forgetting is needed. Like Torres’s other films, Lukas the Strange looks for the middle.

Tell me about Lukas the Strange, or Lukas Nino, as the film is titled in Tagalog. Is the English-language title a direct translation?

The title was supposed to be Lukas Niño [“Lukas Child”]. I was so lazy not to type in the “ñ,” so it became “Lukas Nino.” And “nino” in Tagalog means “whose.” So whose Lukas is this? Does he belong to creatures or to men?

Tell me about how you came up with it.

Man, that’s a hard question. Why do you ask me this?

Well, where did the film come from?

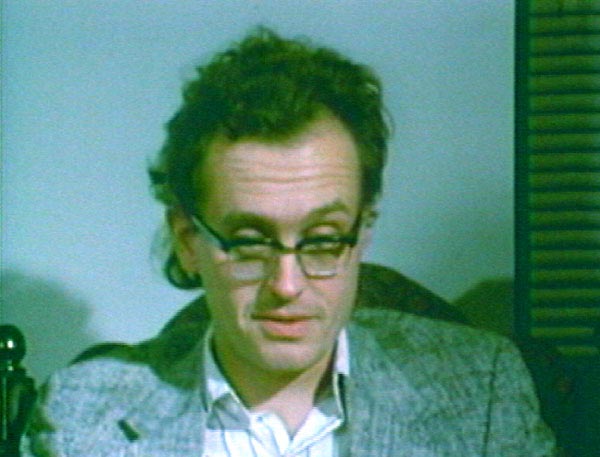

OK. Prepare. I’m going to try to make it really short. I have this film hero, the Filipino director Ishmael Bernal, who’s a contemporary of the better-known Lino Brocka. When festivals think Filipino cinema in the 1980s and 1990s, it’s Lino Brocka, but there’s this equally wonderful filmmaker, Ishmael Bernal, who made his most famous works around the same time. Bernal’s films have a subdued quality to them, a little dream-like, with many things that are unsaid but that you can feel nonetheless, things that are there if you look for them. He has a filmography of 40 films. Around the 15th or 16th title, there’s a lost film. It’s called Scotch on the Rocks to Remember, Black Coffee to Forget (1974). No one saw it, and I thought, “Fuck. The man’s dead, and no one’s even really looking for it.” I didn’t really care what it was. I was just concerned with a space that was left.

I initially wanted—Oh my God, this is going to be a long story. I initially wanted to write a story based on Bernal’s film titles. The sequence of film titles as you read through the filmography chronologically, such that every scene would correspond to a film title, either as a spoken line of dialogue or just looking to the poster of a film for the blocking of a scene. Eventually, though, as time went by, the finances that I had (this film was only supported by the Hubert Bals Fund) weren’t enough to have something very ambitious. I limited myself for the film before the lost film, which is called My Husband, Your Lover (1974). I took inspiration from its milieu and from its major characters and wrote a story. I took out one of the film’s major characters, an aspiring actress. A bit player, a boy seated in one of the scenes as this girl passes him, is Lukas. He is called that because Lukas is my favorite name.

So OK. This is where the milieu and the characters come from. Where another part of the film comes from is one night when I was drinking with a buddy of mine, who’s a poet. He was story-telling the whole night, beginning with, “John, my father, when I was young, told me he was a tikbalang.” A tikbalang is a figure from our folklore. He’s a half-horse, half-man, sort of like a centaur, and a prankster who makes other people lose their way so that they disappear. That’s key—they disappear. I was in a certain mood, and as my buddy was telling me all these stories from his childhood, I began thinking that he was like his father. And how could this possibly be?

At the end of the night we were tipsy. I asked him, “How can you think you are a tikbalang? How did your father tell you this?” And he corrected me: I had misheard one word, which changed everything. He wasn’t a tikbalang—he got tricked by a tikbalang. But by that point I didn’t care. Even in my previous works, I wasn’t fascinated with accuracy or with what really happened. I shot the film before Lukas Nino, Refrains Happen Like Revolutions in a Song (2010), in a land whose language I didn’t bother learning. I didn’t translate the peoples’ dialogue, I just imagined what they were saying and fictionalized everything. I even bastardized all the proper names that referred to their history on the island. I didn’t care. It was my story.

So OK. Cool. There is a third, very important place where Lukas Nino comes from, which is my own experience of watching Filipino films in the 1980s. I was consumed by all these cheesy genre cowboy Western Filipino romantic comedy action films. So consumed, but I also felt a deep self-hatred for liking them. It was an embarrassment. We weren’t supposed to feel proud that we liked this local product, and we are not even supposed to today, especially considering that you have this choice between this crappily-made Filipino film—no color grading, badly dubbed sound, music completely over the top—and slick Hollywood. But the uneven color and unsynched sound were important for me. I wanted to retain them, because they freed me. I’m not so concerned with plot or with story, what I want is feeling. There’s not much of a narrative in my film, I think. But I didn’t care. I just wanted to retain the feeling as a filmmaker wondering, “What if I shot like they did on film?” It’s this older aesthetic that I wanted to capture, even down to little things. For instance, in my film there are no fade-outs, just as there are no fade-outs in old Filipino films—shots start to fade, and then abruptly cut.

All this has to do with my experience of being a moviegoer in the 1980s, though other memories related to cinema have impacted the film as well. Aside from going to the movies when I was young, I got to experience waking up one day and seeing a famous film star on the first floor of our house. People were shooting a film, and she was crying, but only because there was a camera in front of her. Once she crossed the camera, there was a switch, and she wasn’t crying, she was smiling. She played to the crowd. I went out of the house, into the garage, and kicked at just one piece of paper, so that it fell out of position. A crew member told me not to do that again and put the paper back wherever it should have been. It was continuity, and I didn’t know, and I didn’t care, but everything in the house had been transformed. We had been transformed. All the bit players became different creatures and forgot their histories.

What interested you about the people in your film?

The place where we shot the film was my mother’s hometown. I spent summers there during my childhood, but I had not been back between then and making the film. When I returned I just knew that I wanted to talk to my relatives again and see how they had aged. I wanted to catch up on old stories. But I also wanted to be there and try to recreate in my mind how it was to be back in the province, which is around 12 hours north of Manila by bus. While I was curious about the place, I also felt so at home staying there.

Almost all the extras in the film are family members. Before shots, I would tell them the context for the scene—this is supposed to be a film shoot, and we’re shooting this film shoot, so just act normal. It was meant to be like we were casting. And we Filipinos are very, very close to this experience because with our soap operas and our films it’s normal to just have people being asked to play bit roles. They’re at home with this, so the asking is almost never a problem, and in this case there was no difficulty, either. We didn’t have formal discussions about what the film would be, nor about whether they would be paid for their work. They were just glad to be part of it, and wanted to have DVDs to watch when it was done.

The boy who plays Lukas is a nephew of mine who I never really got to know until making the film. Part of the reason for making it was that I was very interested in shooting him, and the film served as a good excuse. I discovered the actor who plays his father through a sort of chance encounter. After shooting for a few days, we realized that we had left something in Manila, so we had to go to the bus terminal to return. It was around 4 A.M., we hadn’t relaxed, we hadn’t slept, and then we suddenly saw this Elvis creature of a man who so rock-and-roll in his movements as he charmed all the women in a small eatery. I knew he was it—I had been looking for someone who resembled a tikbalang. And as it turned out, he was a distant relative of mine.

Tell me about the river of forgetting.

OK. OK OK. I have always vowed to make something simple and easily followable, but always, always, always the films are situated in my history, in our country, and in our past, and these things are not so easy to follow. The river, I think, for me, is a reference to the Marcos dictatorship that ended in the late 1980s. Because I grew up in a household that was largely Marcos loyalist, my picture of Manila was much cleaner than the city actually was. News of bodies disappearing, enemies of the administration salvaged and later found on the wayside, under thick bushes, or thrown in water, were rampant, but I still grew up believing that we needed one strong man, a dictator, to keep society in order. I then thought that we needed discipline as this “new society” moved forward along the road to progress. I was too young to experience needing to be home early because of curfews or having to join rallies. I never had anyone close in my family who was an activist, so I never really knew how it was to see loved ones disappear. But today I always hear of Marcos’s cronies and the military conspiring to take away civilians who were too outspoken against the administration, and when I was making this film, I was fascinated by how the ex-military men are living their lives now.

There’s a big representation in the film of what color people wear, red or yellow. In Filipino history, yellow stands for democracy, and red for dictatorship. (In the film the film crew wears red, and Lukas’s helmet is red and yellow.) I would always think that maybe those people who would want to forget are people like Marcos’s soldiers, who made other people disappear. I think it’s easier for them to forget. They’re wired for crossing the river. Not anyone can do it. It takes great strength and fortitude. I think that they’re the ones who really need to forget.

I was wondering about disappearing bodies. How can one person really think he is a tikbalang? Maybe there’s this cycle of disappearance in his life, and in the 1980s, salvaging people—meaning dumping them into fields so that they never get to be seen again—was done by Marcos’s police and soldiers. These military men are so much like the tikbalangs in my film. By throwing bodies into empty lots and fields, they have also made people disappear. I even imagine them looking like tikbalangs, their appearance mutating, similar to those changes in a soldier’s face coming home after his first experience of battle. Sorrow and guilt housed in a chest for years can mutate someone into a hybrid of man and beast.

So I was thinking maybe if we had the father as well as ex-military men, what if they were thrown into this island together? How would they be able to cope? They would need to invent a river so that they could forget, I thought. (Initially I didn’t know it, but I was making a reference to the River Lethe, which in Greek mythology can supposedly be its own river of forgetting—you forget things if you drink its water.)

And I also need the river. I think that part of the film is my saying that I don’t care about the wounds pain leaves behind. I think it’s much simpler to have this river instead. My past is contained there. Growing up, my father was my idol. He wrote storybooks for children and how-to books for adults, and he earned enough money for us to afford a better life than we would have had without him. I always put him on a pedestal. He was the reason I got started with video-making—he always spent so much on camera and other gear that I was able to start early and use cameras for school projects and practice editing well before college. But my father broke our hearts when I was a young man, when we learned that he had a secret life with another family that lived near us. This is explicitly the subject of my second feature, Years When I Was a Child Outside, but with Lukas the Strange, there is also much of my father in Lukas’s father.

So the river contains many things that have been lost. Lost people. Lost film. Lost instances. Lost moments. But we also find things in the river, like the tapes of this woman guiding Lukas and narrating his story.

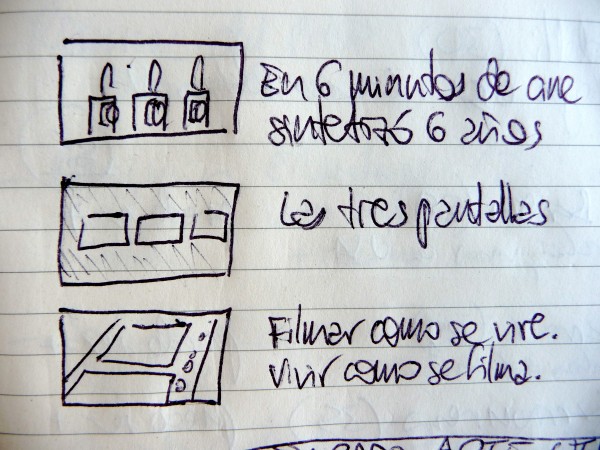

How did you come up with the writing that appears onscreen?

First off, it’s very much ingrained with the process that I’ve set for myself, even with my short films. Inter-titles and subtitles are always onscreen. But with this project we decided that I would use inter-titles when the narrator had difficulty in admitting something to Lukas—something really serious that could change her relationship with him. There are also some things that cannot be said. She tells him, “There are some things that I can tell you, but there are some things that I can’t say.” And these things are presented as titles flashed onscreen while Lukas remains silent.

In my previous works, I have always had different starting points, although process-wise, I think that Lukas the Strange continues my desire to strip down what I have done so far and what I can do and see what else is there, so that I know what remains in my work and what changes in it. One particular difference from my previous work to this film is the use of my own voice for voiceover. Previously, I would always narrate, even in my short films. But I was really tired of hearing my voice all the time, and on this film I wanted to see how it initially was to tell a story without a narrator. Eventually, though, that didn’t seem right, either, and I felt the wrongness in my gut. I thought I was missing someone. I was missing my friend who was telling me about his father and about his true-to-life childhood. I missed this possibility of mishearing this narrator/friend, this chance to hear someone who might be making up or mixing up the story after all. I missed the confused voice of a troubled soul. And so I made a big, big creative decision to have this witness—or this friend/muse—narrate everything. This person who is everywhere, who is somehow remembering all these things—not exactly creating from scratch, or representing what really happened. She’s telling a story.

Do you believe there is love in Lukas the Strange?

There’s love. Love is my first instinct, my first impulse to do this. It’s always about this, in this film as well as in my others. And I can’t tell you in words how love is vital to them, so maybe the films are enough.

All images accompanying this interview were provided by John Torres. The interview was conducted at the 2013 edition of the International Film Festival Rotterdam, which also screened a film produced by Torres. Shireen Seno’s Big Boy tells the story of a postcolonial Filipino family stretching their first-born son’s limbs as far as possible in the name of progress.

]]>

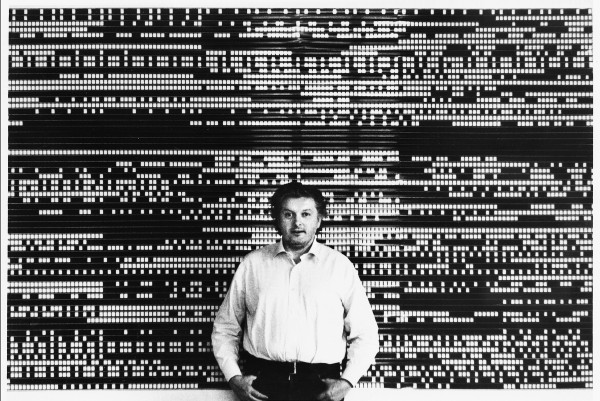

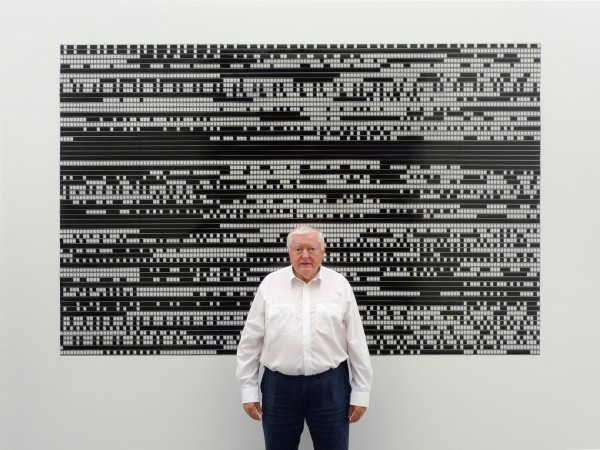

Austrian avant-garde filmmaker and theorist Peter Kubelka likes to speak of the “now moment.”1 If you’re lucky enough to sit in on one of his legendary, inimitable lectures, you’re liable to see him illustrate these “now moments” with the ring of a Buddhist bell, or with a rhythm tapped out on a pair of Japanese woodblocks, as he chants contentedly his presentist mantra: “Now…now…now….” For Kubelka, it is the precise nature of the film medium to deliver twenty-four such “now moments” every second.

Of course, each of these “now moments” conceals eons of protracted labor: Kubelka’s work is some of the most exactingly wrought in all of cinema. In a 1967 interview with Jonas Mekas, Kubelka mused that his output to that date amounted to fewer than eight frames per day.2 (Later, he would only get less prolific.) This methodical precision inarguably lends his “now moments” an intense charge: one characterizes the films of Peter Kubelka in terms of impact, in terms of density and an explosive force which persists unabated upon the second, third, and fourth viewing. Mekas celebrated “the incredible artistry of this man, his incredible patience,” describing 1966’s bracing, incomparable Unsere Afrikareise as “about the richest, most articulate, and most compressed film I have ever seen. I have seen it four times and I am going to see it many, many times more, and the more I see it, the more I see in it.”3 Stan Brakhage recognized that “Kubelka takes a very long time making each film a lasting experience of the moment of enjoyment—so that each can be seen again and again for increasing fulfillment of the initial experience.”4 Both Brakhage and Mekas thus encounter the pressure of accumulated time in Kubelka’s constructions, a potential energy that, like a clock wound to infinite tension, proleptically sustains an unlimited number of viewings.

Indeed, though Mekas found something crystalline and organic in their compressed imagery, Kubelka’s classic works from the fifties and sixties strike me as elegantly, delicately artificial; clockwork-like, reflecting Kubelka’s enthusiasm for the lost art of the handmade timepiece. It is perhaps the grotesque song of the cuckoo clock which resonates in Unsere Afrikareise. In a comprehensive new documentary, Martina Kudláček’s Fragments of Kubelka, the now 79-year-old filmmaker recounts an experience in Africa in which a group of drummers began to strike a rhythm precisely at the moment the setting sun hit the horizon, a prototypical instance of the audiovisual “sync event” so abundant in cinema. It is the production of such orchestrated “sync events” which makes Unsere Afrikareise tick. Hired to document this African hunting safari by a group of bourgeois Austrians, Kubelka radically subverted the footage and audio, condensing the material into hundreds of multi-layered sound-image correlations. Early in the film, the sound of a gunshot accompanies the image of a hat blown off in the wind, jolting the viewer like a wake-up call into active perception. This and other “sync events” betray the fact that animals aren’t the only targets in Kubelka’s lens. Despite the leering glimpses of “natives” and wild beasts, nothing in Unsere Afrikareise is more savage than its bleak irony. A cartoonish soundtrack, somewhere between concrète and Carl Stalling, scores images of felled beasts and fetishized black bodies; throughout, the alarming, brutish off-screen guffaws of the Austrian hunters serve as laugh track, implicating filmmaker and audience alike in a cruel, racist Looney Tune. It is this cuckoo laughter that serves as the film’s rhythmic element alerting the viewer to the complicity of hunter, filmmaker and spectator in the “now moment” of colonial oppression.

If a European cuckoo-clock rhythm of laughter inflects Unsere Afrikareise, the rhythms of his earlier “metric films” bring to mind the metronome and the stopwatch. Though the metric films lack the political and ethical complexity of Unsere Afrikareise, they also share an interest in testing the viewer’s perceptual limits. Kubelka conceives of 1956’s Adebar and 1958’s Schwechater as precise systems imposed on time’s endless continuum, rational schemes emerging from an immeasurable flux. Exactly a minute in length, these films function on principles of regularity, division, and repetition, a reminder of the debt the cinema projector owes to the chronometer, to the moment of industrialization when the clock started watching the worker as much as the worker watched the clock. These films are cinematic stopwatches, by which the viewer is submitted to a kind of “time trial:” as rapid, inscrutable clusters of high-contrast single frames flicker from between stretches of black leader, watching Schwechater feels like a perceptual-synaptic responsiveness test.

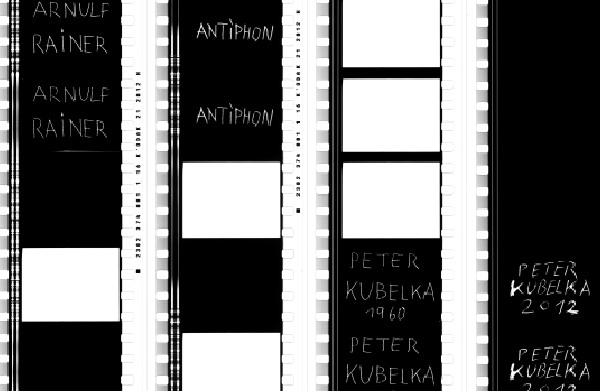

In the history of experimental cinema, then, Kubelka stands as the first to make films that experiment on you. And no film better manifests this strand of the avant-garde than the first “flicker film,” 1960’s seminal Arnulf Rainer: to many acolytes of experimental cinema, it stands as a timeless revelation of the film medium’s “hard core;” to others, it represents nothing more than an endurance test. While it’s hard to imagine that a film as abrasive as Arnulf Rainer was not conceived as an assault (which, if it were true, would have made it an enormous success: it cleared the room at its premiere screening and cost the artist most of his friends),5 but I believe Kubelka when he claims, “my intention when making films is not a wish to entertain, but rather that of a scientist who does his research.”6 To apply the cliché of “clinical precision” here seems more than justified, since it so purely eliminates film’s stochastic variables, reducing cinema to its most fundamental components. At one key moment in Fragments, Kubelka describes the making of Arnulf Rainer with the characteristic concision we find in his films:

“The structure of my film is metric. It’s sixteen even parts. The elements are only the four basic elements of cinema: sound, silence, light, darkness. All the elements have the same length, namely a twenty-fourth of a second. And out of that simplest film language, I built then my ecstasy.”

It is worth pausing on each of these last three words. Among them, “ecstasy” appears at first the most suggestive. Arnulf Rainer remains a psychedelic experience both in spite of and because of its aspirations to science, reminding us of the moment when LSD was at once an object of serious medical study and a promising gateway to spiritual revelation. While formally ahead of its time, it is in this sense much of its moment, a moment before psychedelia left the clinic once and for all. The phantasmic geometries and spectral hues we encounter between Arnulf Rainer’s stroboscopic frames emerge not from the film itself but from mysterious subjective processes of ocular and psychological response. Like the ecstasy we read in the upturned eyes of Zurbaran’s Saint Francis (1640-1645), Kubelka’s ecstatic vision takes place not before the eye but rather behind it. Indeed, much like LSD, Rainer proved far more influential for its experiential impact than for its scientific rigor. Filmmakers like Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits built upon its flickering template not so much to define the basic parameters of cinematic form as to refine its phenomenological, psychedelic potential.7 Partly because of its underground popularity, critic Parker Tyler saw a “new experience of psychedelic time” in Rainer’s “chemical aesthetics,” fretting that the “hypnotic” qualities of Rainer’s “purely formal rhythms of sight and sound” had a cultish appeal: “Just as under certain drugs or perhaps actual hypnosis (we think of a snake fascinating a small animal), a human subject may find the greatest “aesthetic” reward in the simplest repetitive movement of some object or objects, provided the movement is rhythmic, so, exactly, may a viewer of Kubelka’s films decide, if sufficiently indoctrinated with the Brakhage-Mekas creed, that ‘Kubelka is the worlds greatest filmmaker’ (Brakhage).”8

Despite the reactionary attitude, there’s a kernel of truth in Tyler’s remarks: the sustained importance of and interest in Kubelka’s films and thought, so amply manifested by Fragments of Kubelka, can be attributed both to his brilliance, and to the crucial support he found in Brakhage and Mekas. In 1966, after a string of professional catastrophes, Kubelka received an invitation from the two to bring his work to America. While a guest of Stan Brakhage in Colorado, he put the finishing touches on Unsere Afrikareise; the film debuted in October of that year at the Film-Maker’s Cinematheque in New York on a program, organized and promoted by Mekas, which also included the earlier trio of “metric films.” As Kubelka recalls, the American trip was the first professional success of his cinematic career—we might say, his first “sync event” after spending fifteen years ahead of his time. Playing to an audience that included Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Ken Jacobs, and others, Kubelka’s films found a willing (and paying) audience of interested equals, while the filmmaker himself was given the opportunity to share his idiosyncratic theories of cinema in a series of lectures which changed both Kubelka’s life and the course of American avant-garde cinema in the following decade.9

As a sudden surge in filmmakers and theorists interested in medium specificity and abstraction took up the challenge of this work, Kubelka could no longer call Rainer “my ecstasy:” it was no longer his alone. Witnessing his project carried forward by a new structuralist-materialist avant-garde, it was at precisely this moment that Kubelka himself backed away from cinema. Increasingly in demand as a lecturer, Kubelka began in 1967 what he calls a period of “despecialization,” seeking a larger vocabulary with which he could express his ideas. Whereas until then, Kubelka had focused intensely on the film frame as a compositional unit, he now sought a new way to “frame” film culturally, turning to the study of cooking, anthropology, and music to situate cinema within the larger field of human endeavor. Fragment of Kubelka admirably charts the course of this capacious erudition, a horizonless field of curiosity for which cinema steadfastly provides both an anchor and a rudder. In excerpts from lectures and spontaneous dialogues, Kubelka utilizes this expanded cultural vocabulary to eloquently illuminate the natural and organic inspirations behind works which to me always seemed so mechanical: the diurnal, night-and-day rhythms of Arnulf Rainer, the “structural image of fire and of a running brook” in Schwechater.10 Because the intervening decades have revealed how vastly the scope of his interest has extended beyond the film frame, and because he has steadfastly refused digital transfer of his film works, Fragments of Kubelka ultimately succeeds most in paying tribute to the post-’67 period of its subject’s life and thought. While his films surely exhibit a remarkable longevity, they appear in Kudláček’s narrative as moments, stations in a path. Kubelka’s cinema—that is, the cinema as he understands and reveals it, as an expression of the human will to comprehend and transform space and time—is timeless.

Which brings us, then, to “then.” Kubelka uses film as a way to understand time—as space, as Heraclitean flux—but not to understand the past. In their emphasis of the filmic over the profilmic, Kubelka’s films can only come alive in the moment of attentive spectatorship. But what does it mean when, as celluloid becomes another stone-age relic, the “filmic” becomes a metaphor rather than a material reality? What does it mean to recapitulate the past of a filmmaker who has always privileged nothing more than the “now moment?” It might be fair to attribute Kubelka’s inability to complete Denkmal für die Alte Welt (Monument to the Old World), a film he first planned to exhibit in 1977, to this adherence to the “now moment,” were it not for the fact that his most recent (and, by all accounts, final) cinematic effort bears the similarly memorializing title, Monument Film. Recapitulating and expanding the radical formalism of Arnulf Rainer after fifty years, Monument Film suggests both an act of personal recollection and an elegy for film itself. If Monument Film is the elegy, then Fragments of Kubelka (which, at four hours, is itself a kind of monument) stands as a more conventionally discursive eulogy.

So, is Kubelka winding back the clock, or is he winding it down altogether? In Monument Film’s last sequence, two projectors show Arnulf Rainer superimposed upon a new film, Antiphon, which inverts the original’s schematic arrangement of black frames, white frames, white noise and silence. The sequence appears as six and a half minutes of pure white light and white noise—thus containing all possible filmic images and sounds within—mitigated only by the inconsistencies of dual projector synchronization. Another “sync event,” to which we could add the simultaneous appearance of Fragments: both seem to sound the funeral drum as the sun sets on the age of cinema. This would be a cause for grave concern, were it not for the optimistic words of Kubelka himself:

“There is a new global avant-garde working exclusively with photographic film, there is a growing international lab movement backed by thousands of young film artists. The phoenix will rise from the ashes. I do not doubt that in the least.”11

So a bright light may be flickering somewhere in the future, after all. Which, in a way, puts Kubelka right back where he was in 1960 making Arnulf Rainer: still ahead of his time, looking at his watch, waiting for the world to catch up with him.

- If you haven’t been lucky enough to catch one (me neither), and you don’t live close enough to New York to catch the run of Martina Kudláček’s Fragments of Kubelka starting Friday at the Anthology Film Archives, there are a few online, such as this one, filmed at London’s Drawing Room gallery on June 16, 2012.

- Jonas Mekas, “Interview with Peter Kubelka,” in Film Culture Reader, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Praeger, 1970), 296.

- Jonas Mekas, “On The Supreme Mastery of Peter Kubelka,” in Movie Journal: The Rise of a New American Cinema 1959-1971 (New York: Collier Books, 1972), 258-259.

- Stan Brakhage, “On Peter Kubelka,” in Film-Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue No. 4, 1967 (New York), 183.

- For an account of this screening, as well as similarly confrontational screenings that followed, see P. Adams Sitney, “Kubelka Concrete (Our Trip to Vienna)”, Film Culture no. 34, Fall 1964, generously scanned and posted at http://making-light-of-it.blogspot.de/2012/07/kubelka-concrete.html.

- Pamela Jahn, “Monument Film: Interview with Peter Kubelka,” Electric Sheep Magazine, April 3, 2013. Accessed April 25, 2103, http://www.electricsheepmagazine.co.uk/features/2013/04/04/monument-film-interview-with-peter-kubelka/

- “The film-makers who followed Kubelka in exploring the possibilities of the flicker film in either color or black-and-white have tended to conceive it differently. For Kubelka, Arnulf Rainer is the absolute film, the alpha and omega, which both defines and brackets the art. For the structural film-makers who use the flicker form, it is the vehicle for the attainment of subtle distinctions of cinematic stasis in the midst of extreme speed which can be presented so as to generate both psychological and apperceptive reactions in its spectators. Although Kubelka is not closing out the possibility of such reactions, he created his film as both a definition of cinema and a generator of rhythmical ecstasy.” Sitney,Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943–2000, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 288.

- Parker Tyler, Underground Film: A Critical History, (London: Penguin, 1971), 61-62.

- Kubelka describes the trip and its importance to his career in an interview with Scott Macdonald, “Peter Kubelka: On Unsere Afrikareise (Our Trip to Africa)” A Critical Cinema 4: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 177-178.

- Sitney, Visionary Film, 287.

- Peter Kubelka, quoted in Stefan Grissemann, “Frame By Frame: Peter Kubelka,”Film Comment, Sep/Oct2012, Vol. 48 Issue 5, 75. Accessed online April 25, 2013, http://filmcomment.com/article/peter-kubelka-frame-by-frame-antiphon-adebar-arnulf-rainer

It was an October afternoon last year at the Brooklyn screening space UnionDocs, and our group of five was awaiting David Gatten. He arrived distinctly attired—small-lensed glasses, a scraggly beard, overalls, and a heavy knapsack, from which he removed prints of eight of his eighteen completed 16mm films. Some he hadn’t brought because he’d made them to be shown at an outdated projector speed; one was unavailable because his print remained in California under an old girlfriend’s care. But the films he had on hand he would project himself and discuss with us.

This is a frequent practice for Gatten, who was in New York for the world premiere of his latest work, The Extravagant Shadows, at the New York Film Festival’s Views from the Avant-Garde sidebar. We arranged our private screening because we might never see his remaining works otherwise. His films are unique art objects, rendering chances to view them rare. He explained that no more than three prints of any exist; some, like the What the Water Said series (unprocessed filmstrips exploding with sound and color, the product of Gatten leaving them floating in crab traps off the South Carolina coast), could never be reproduced. Each time a film of his runs through a projector, he said, it dies a little.

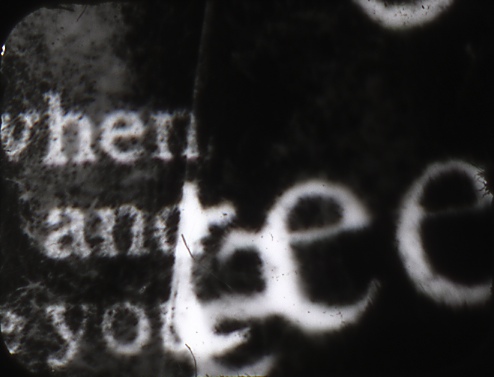

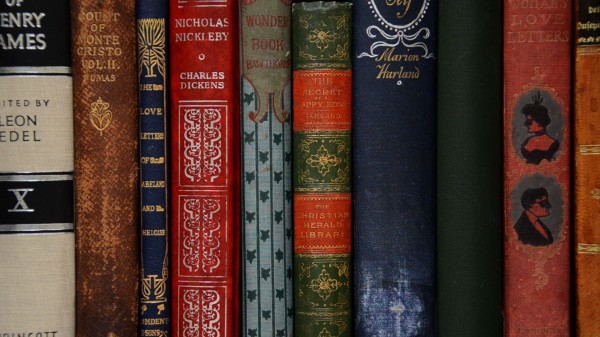

These delicate, fragile works need care and attention to survive, much like a key Gatten subject: love. And like much of the output of his self-professed model, Hollis Frampton (whose ode to his own maternal grandmother, Gloria! [1979], is Gatten’s favorite film), they devote themselves to building systematic frames within which love can be articulated. The frames are often made from forms of written language, whether densely coded Western Union messages (Film for Invisible Ink, case no. 323: ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST [2010], prepared for his wedding to fellow filmmaker Erin Espelie) or phrases plucked out of direct, despairing summons written to a beloved from across an ocean (The Great Art of Knowing [2004]). His most celebrated project has been an ongoing nine-part film series, begun in the late 1990s, called The Secret History of the Dividing Line, with each entry named after a book belonging to 18th-century Richmond, Virginia founder William Byrd II, whose library contained over 4,000 volumes. The series’ four completed films, all silent (though Gatten prefers to call them quiet) and three of the four in black-and-white, tremble with close-ups of thick, richly engraved words soon to disappear from sight.

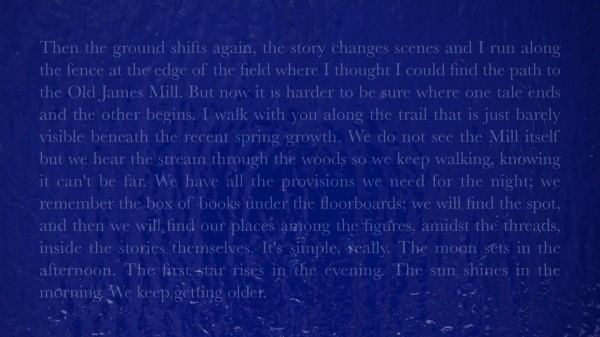

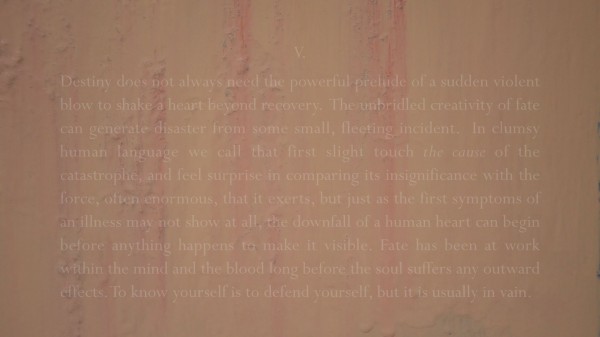

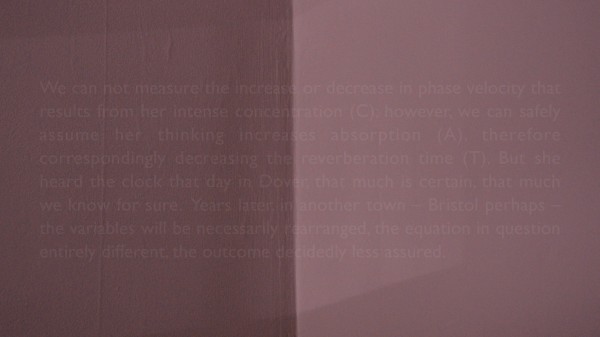

It takes words much longer to vanish in The Extravagant Shadows, Gatten’s first digital work, which will be screening again in New York (in a session curated by Views programmer Mark McElhatten) at Lincoln Center on Monday, April 29 at 7 P.M. with Gatten in person. They fade in, ghostlike, forming cryptic messages over layers of paint with which the artist has covered a bookcase’s glass front, then haunt the screen for several minutes as they fade back out. Though many originally come from other writers, including Stefan Zweig, Maurice Blanchot, and Henry James (from whose short story “The Jolly Corner” Gatten took Shadows’ title), the tale that they obliquely tell—made up of overlapping possible stories that lovers might share, if chance allows—is of Gatten’s invention.

How did you learn to read?

I cannot completely remember learning to read, but I know that books were always a tremendously important part of the household. We did not listen to a lot of music. Music was not on all the time, and was a very special event when it was played. Books formed the architecture of our home. My mother majored in Shakespeare at William & Mary. My father would read to us for an hour every night and my mother would read on the weekends. My earliest memories of literature are of having it read aloud to me. I am certain that Dr. Seuss was an important beginning, and I feel like I learned to read and took pleasure in reading early on. My parents would take us to the library every week, where we were allowed only three books. That wasn’t a library policy, but a family policy, which put into place an idea of scarcity, and a need to then choose carefully. Books were serious and special things. So I spent all of my allowance money on buying them.

My relationship to the written word became problematic when I tried to learn to write cursive, because in the 1970s in North Carolina public schools, if you were left-handed you were still referred to as “the Devil’s child.” As a left-handed person I was too much for the teacher, and was put in the corner with crayons to draw while everyone else learned to write. I have never had an easy relationship with my own handwriting, and in fact, much of the time I cannot read anything that I write. I believe that this problem has become a fundamentally important condition for my thinking about text as image in cinema, and issues of legibility and illegibility. Hardwood Process (1996) is largely a movie about my inability to read my own diary. The film has 14 sections, each beginning with a phrase. It’s all stuff that I couldn’t read, but that I knew was important. So I had to make images to complete the phrases. Even today, at age 41, I am still frequently unable to read something I have written by hand. I am still learning how to read on a daily basis.

How?

I’ve learned to read very differently based on the kind of books I have been reading. David Markson is one of the two “skeleton key” writers that have inspired and informed my cinema—the other being Susan Howe, especially her book The Non-Conformist’s Memorial (1993), and within it the poem “Melville’s Marginalia.” Although my method of writing and condensing writing was pretty well developed by the time I read Markson’s This Is Not a Novel in 2001, I feel I was deeply altered by it—and then also by a subsequent reading of Vanishing Point (2004). I found it both one of the funniest and one of the most emotionally devastating reading experiences of my life. I think there could never have been the Films for Invisible Ink [a series of films specifically made for friends and loved ones]—especially the first one, Film for Invisible Ink, case no. 71: BASE-PLUS-FOG (2006) [made for Gatten’s first wife, Weena Perry]—without it. And I’ve been going to school with Markson ever since. Those last five novels of his speak so strongly and directly to a poetic and narrative strategy that I find moving as a reader and, at this point one happily and nearly inevitability at play in my own work as a filmmaker. Touchstone works by a writer of enormous humanity.

I also learned how to read over the last seven years from reading Henry James.

How did James inform The Extravagant Shadows?

“The Birthplace,” the short tale in which the young couple is caretaking Shakespeare’s cottage, is the first James text that appears. It initiates a narrative about a young couple going to live in a place that is inhabited by a spirit they can’t see, but with whom they want to commune. I used this tale as the launching pad. It immediately seemed related to, but different from, the James tale, “The Jolly Corner,” which is about a man who is going back to a house that he owns but hasn’t been to for years, and who, as he starts to visit it, also starts to recognize the life he might have led. “The Jolly Corner” is, in my reading, very much about a consideration of another self. Those two stories I had read many years before and confused. They had been condensing for years in my brain before I came back to try and capture something of them on paper.

So there were situations and a narrative thematic that James provided immediately. But much more important was the way in which he deploys language to describe a series of events, which might be actions in the external world or the internal clockworks of emotions and of decision-making processes. The way he will circle around something, with the most important things being what he leaves unsaid. He makes beautiful outlines with language. I was interested in the specific instances of language he uses to do that, but also in his greater approach to storytelling. All of the storytelling in The Extravagant Shadows is based in a late Jamesian mode of proceeding through an event, an idea, a character, or an emotion.

James is there in almost every panel of text. I wrote most of the text myself, but I was writing in relation to James almost the entire time. James makes visible the process of thought, which of course happens very fast, but through his use of language, he slows it down so that we are able to understand someone else’s thinking. A character’s, but also his own, with all the hesitations and circling back in slow motion, which allows for analytic examination. With The Extravagant Shadows I’m trying to do that. I don’t think it’s a slow film, but it is a place to reside in for a long time. I hope that there is a lot of time to consider small details, whether those are details of language, of paint, or of light shifting.

How did The Extravagant Shadows form?

I have always worked slowly, but the older I get the slower I am working, and the longer I am willing to work on a project. The Extravagant Shadows began in 1998 with an idea about certain pieces of language, based in Blanchot. I knew I wanted to make a work where language was staging itself very, very slowly, much more slowly than I could accomplish with what I knew about filmmaking at the time. I was in graduate school at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and was doing a lot of contact printing and optical printing. On a contact printer the longest fade you can have is 96 frames, or four seconds. On a small JK optical printer it’s very difficult to make something longer than four seconds, and I knew I wanted fades to last minutes, and for things to hover on the edge of legibility for minutes. I knew that I wanted to work with an analogue video image and text generating, so that I could have a different kind of control over time. I assumed that this work was going to be an analogue tape. There was very little text then compared to what there is now. It was going to be a much shorter piece, maybe half an hour long. But I didn’t know how to make it, and it wasn’t urgent to make at that moment, and other projects took over. This was at the same time that I was discovering the Byrd project, and that took hold strong. So The Extravagant Shadows, which wasn’t even called that then (I think it was called Area Effect), just sat.

I came back to it a few years later and fiddled with the text some more. A lot of what I do in the studio is sit and write. I’m not always working with strips of film. I’m not always in the darkroom. It is often reading and writing. The studio is a place to consider words, and to structure my own words, as well as to produce images. So I would write. Sometimes if I got stuck on another project I would return, but I mainly kept putting it aside, and putting it aside. I’d shot some stuff on VHS that didn’t have anything to do with the images that we’re looking at now. I was actually shooting a TV monitor of a snowstorm on bad antennae reception. There was the snow of the storm that the weather channel was covering and there was the snow on the screen itself, and that was serving as a background for these words to emerge from. And I thought that that was interesting, but I wasn’t wild about it. I knew at a certain point that I was going to work with a mini-DV camera, but that didn’t end up going anywhere either.

Then I moved to New York in 2006, finished the first Invisible Ink film, BASE-PLUS-FOG, and went back to what, at that point, I knew to be The Extravagant Shadows. I was reading Henry James on a daily basis, and conversing with a friend who was also reading James. We would wake up every morning, call each other, and ask, “What’d you read last night? How was it?” For two years we were reading James almost every day. Mostly not the novels—mostly it was the tales. We systematically made our way through nearly all 112 tales, and talked about them, and that is when the piece started to find the shape that it has now. I knew it was going to have a Jamesian structure, that the characters, the situations, the ambiguities, the events would have something to do with the way James represented the world through language. And that there would be phrases, but that I was going to write through them, around them, and to connect things from a dozen of the different tales to make a new story that doesn’t exist in any James tale, that doesn’t exist in any Blanchot book, but that borrowed from and condensed them.

I use the term “condensation” in relation to texts. I am trying to build cinematic structures that replicate the process of condensation within a glass of water, allowing for things that are in the air to be fixed, find new form, and group together as visible, light-catching substances. What I’m trying to pull out of the air is language. These cultural productions that exist as books, I’m trying to build a cinematic structure to condense them. It’s an active reading process, first of all. It’s recognizing that this phrase connects to this phrase, and that if there’s this idea here, and there’s another idea 18 inches away, I’ve got to then use language to make the connection to draw these two things together. I believe that poetry often operates as a kind of condensation which functions through ellipsis, an economy of means, and a high level of organization. Shape is important in poetry. It’s deeply important in prose as well, but there it’s articulated in a different way, and often at a different length. I am trying to boil down experience and language into a smaller vessel. I am still working out this poetics, and am just starting to understand it as a tool, rather than something that I recognize that I do. I didn’t say, when I started doing this, “Now I will condense this text.” I just found myself doing it, and it was during the last couple of years of writing The Extravagant Shadows that I came to understand it as an approach that I can apply to any existing text to make a set of new meanings. To take, as I do, a Wallace Stevens poem, “Description Without Place,” and condense it into 24 lines by taking certain ideas, leapfrogging over others, and forming a new poem. With Stevens, with James, with Blanchot.

That writing process took up a lot of time. But it was only once I started teaching at Duke University in 2010, and once Erin and I moved to the cottage we live in when we are at Duke, that things really coalesced. I started shooting the cottage walls because I love the colors the walls are painted, which were the existing colors when we moved in. Home is really Salinas, Colorado, all of our things are in the cabin there, and the Durham cottage is quite minimal by comparison. We don’t put things on the cottage walls. The walls are painted, and the paint is beautiful. I felt that the walls were speaking.

In 2011, I started filming—not filming, but shooting with Erin’s Nikon D-7000. I started making images and recording sound in the cottage. I was so inspired by the paint that I wanted to start painting myself, mix paints, and experiment with layering colors and producing effects of color and light rendered digitally. All of the painting that we see in the final form of The Extravagant Shadows was performed in May, June, and July of 2012 in Colorado outside the cabin. It was very important to do the painting outside, where the clouds could move across the sun and change the color temperature and affect that world of paint. I didn’t want it to be a static, studio-lit situation. I wanted low relative humidity to help the paint dry, and I wanted the paint to be alive to the changing of light.

So it was a circuitous path, with a lot of stop-and-start. And then, as there often is, there came a moment when I could think about nothing else. I was intending to finish the new Byrd film, but The Extravagant Shadows said, “No.” I was so surprised. I’ve been making work for a while, and I know what I’m doing as a 16mm filmmaker. I’m deeply surprised about what happened with digital cinema and The Extravagant Shadows.

What is your background in painting?

It stretches all the way back to May of 2012. I had never painted anything before then, except for places where I had lived, where I was just painting the walls. I wasn’t painting pictures, I was applying paint, which I like to do, but I had never painted before. I like to look at paintings a lot, though. Adriaen Coorte’s painting White Asparagus at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam—in which the white paint has faded to the point at which the image of the asparagus is really a translucent ghost of itself—is probably my favorite painting. And then I often think most of my filmmaking operates in relation to experiences I’ve had with Agnes Martin’s work.

Part of what I’m interested in in cinema is exploring materials. With the What the Water Said project, I put into play the substances of the ocean, the river, and the filmstrip. I didn’t know what was going to happen—all I did was throw the celluloid into the water. With The Extravagant Shadows I chose different kinds of paints. I chose oil-based enamel paint and acrylic paint, and I layered those on top of each other and let them make the picture. I didn’t control—I just wanted to see what would happen with the relative humidity of the air, the intensity of the sunlight, and the way that those paints reacted to each other. They’re not made to be used in tandem like that. So it was about letting the materials articulate themselves.

As the movie goes on, I start to do things with the brush to provide different conditions for them to articulate themselves into different kinds of images. The paintbrush starts to activate different characteristics of the paint. It starts to layer or smudge things, or work with one layer before the other layer is completely dry. I was learning. I was listening and watching the paint as the shoot went on, and trying to respond to what I was learning. I then started making some paintings, but found that they weren’t interesting to me. What I was interested in was seeing paint dry. As soon as the paint would dry, I would apply more paint, so that it was never dry and always drying. The painting never finishes. It never stabilizes. It’s always changing.

What are the extravagant shadows?

For me, first and foremost, they are language. It’s the words themselves—and the ideas, stories and emotions they describe—that can’t be contained, erased, painted over. They are so extravagant that they cannot be effaced. I was keenly aware when making this that it was a digital work, and that as a digital work, it in some ways flew in the face of the aesthetics of the mostly black-and-white 16mm Byrd work—and most everything else I’ve made. And many of those films—The Great Art of Knowing [second film in the Byrd sequence], The Enjoyment of Reading (Lost and Found) [2001, fourth film in the Byrd sequence], the new, still-unfinished Byrd film in particular—are filled with shadows, with dappled light, with extravagant expressions of light and dark, kinetic (and I believe beautiful) expressions of light modulated through shadow. Those films are filled with extravagant shadows. My guess is that when people see this new title and think of my work, they’re thinking of visual shadows. But I wanted to get at something less literal. The early gesture of painting out the books is, I think, a notice that this isn’t going to be the same space. We’re not going to be considering the book-as-object. We’re going to be considering what the book contains, and what it might evoke, as opposed to represent. There are shadows in this digital work, and there are reflections, but they are considerably more subtle, although perhaps no less extravagant, than in the 16mm work.

Do you feel these shadows coming to life?

That’s the goal, and I hope they do. I ‘m moved that viewers thus far have seemed so committed to giving them life through their attention. That’s the only way they can come to life—through someone’s concentrated and generous imagination.

There are certain kinds of movie experiences—which I love having—where everything is largely determined. If you go to see the Lord of the Rings movies or the Jason Bourne films or a Soderbergh in a certain mode, then you are going to live inside a world that is built almost airtight and perfectly articulated. You will identify with characters, you will lose yourself, the meaning is blazing off the screen, and you are actively subsumed in it. This is one kind of experience, which commercial cinema frequently seeks to produce.

My background of consuming and enjoying that probably helped me conceive work that was different from commercial cinema, and closer to the aesthetic experience of the fine arts. I admire the idea of the oppositional cinema, but what I’m making is just in favor of itself, and not necessarily opposed to something else—I like the other thing too, it just isn’t what I’m doing. I prefer to think of cinema as an ecosystem with different kinds of works existing at various points along a continuum rather than simply being in opposition to each other. For the kind of experience I seek, I don’t want anyone to forget who they are or where they are, and I want my viewers to be active in a different way. I want the chief activity to be that of the viewer approaching the screen, and for the meaning of the work not to be inherent, but rather to be a product of someone’s engagement with it.

Now, that is not to say that anything goes.Rather, it means that my job as a filmmaker is to define a field of play containing multiple paths. This is what Umberto Eco describes in his great book, The Open Work (1962). When I encountered that book in graduate school it articulated many things that I was feeling about experimental and avant-garde cinema and that I admired, but that I couldn’t articulate for myself.

Why don’t you attribute the source texts in The Extravagant Shadows?

I have made some attempt at attribution in the printed material, but not in the work itself. I use other peoples’ texts in almost everything I make. Quite often there are attributions at the end of the films, and quite often there are not. My name appears at the end of some works and not in others. Because that is a shot, it’s not just credits. That’s the last shot of the movie. I am thinking about these things as images. I could not possibly end Secret History of the Dividing Line [2002, first film in the Byrd sequence] after the words “Here ends the Secret History” by then putting “David Gatten 2002.” That would be preposterous. That would be another image. Here would not have ended the secret history: it wouldn’t be over yet. I would never put my name at the end of The Great Art of Knowing. That would be like a desecration of what I was trying to do. Yet at the end of the next two Byrd films, I not only refer to texts, but my name is on the films. In Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handy-Works Applied to the Art of Printing [1999, third film in the Byrd sequence] I cite the translations, the translators, sometimes the press itself, because that was a book about translation and the printing press, and so that is an appropriate image with which to end that film. That wasn’t an image that I wanted to end The Extravagant Shadows with. I wasn’t going to go to a black screen after those books. The last image of that film had to be book spines. So there was not an appropriate place within the image sequence to put that attribution information. It’s not secret. It’s not that I don’t want people to know. It’s just that there is not an appropriate place to relate that onscreen. It’s an aesthetic concern. Other filmmakers often use credits as bookends. For me they’re covers.

Did you see a similarity in the relationships between celluloid and digital photography and between the physical book and digital text?

I didn’t think much about digital text—in the form of electronic books or reader devices per se. I’ve seen people on the subway carrying these E-readers, but I’ve never actually held one nor tried to read from one. So I suppose it is amusing at some level that I’ve made a three-hour movie that is all digital text and is essentially an electronic reader. I really wasn’t thinking about it in those terms while making it—I was more concerned with, and interested in, the difference between working with celluloid film titles and computer-generated text. Of course we’re going through a tremendous change in print culture—we can’t even call it print culture anymore—reading culture—in the same way that we are going through a transition with the moving image. I have addressed this before. The transition from celluloid to digital I was trying to get at in 1999, when I made Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises. Joseph Moxon produced the first manual of style to tell printers how to print. I was trying to go back to the moment when we moved from scribal reproduction to mechanical reproduction of texts with Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible. One can then draw the celluloid-digital analogy within The Extravagant Shadows, where at the beginning I put the books away and then bring out the text. The object disappears, but the text persists. I suppose at that level it is some sort of comment on the status of the book in the 21st century.

It is largely a quiet film, but there is some sound. How did you make your soundtrack choices?

The music—five songs from a 1968 Merrilee Rush album called Angel of the Morning—I took as the soundtrack. I was interested in using those songs as texts in the exact same way I was considering works by Henry James, Stefan Zweig, Roger Gard, and Lao Yee-Cheung. They are conveying narrative information, in a voice that has emotion and phrasing. I was thinking of the songs as another set of texts, manifesting language differently. Not just onscreen, visual language, but sung language. And all of those songs have particular emotional dynamics that intersect with some of the narrative thrust or the situations in the other texts.

That’s about the music. One of the big differences between shooting 16mm film on a Bolex and shooting digital images on a Nikon D-7000 is that the digital camera assumes sound. It automatically records synchronous sound, whereas a Bolex does not. It’s actually tortuously difficult to record synchronous sound in film. You’ve really got to make a point of it. And with a Digital SLR (DSLR) you’ve got to turn off the sound. You’ve got to go to a bit of trouble to make it a silent recording. So it felt important to acknowledge that, and to let there be a moment where the image gains dimension through the genuine synchronous sound of a particular place. I make that gesture at the moment in the movie when I want to address sound. Up to that point—one hour and 18 minutes—there has been a lot of mention of sounds and spoken language. In all sections of the narrative thus far, the text speaks about characters hearing things. So I hope that we are primed as viewers to already be thinking about what it means to hear something. I then wanted us to hear something, and then I wanted that to go away. It was important to explore something that I had never explored before, but that is inherent in working with a new digital camera.

A few days before I saw the film, you told me that Hollis Frampton’s film Gloria! would help me make better sense of it. It might have been because of the way that Frampton uses music. How do you see the usage of music in the two films as synchronous, and what other synchronicities do you see?

When I saw Gloria!, I felt Frampton was almost reminding me that music is appropriate, in the same way that I think he reminded a lot of people that language is an appropriate area of exploration. Coming out of an American avant-garde cinema as articulated by Stan Brakhage, which was largely about a perception beyond or before language, Frampton brought us back to language. And I experienced very powerfully his use of music. But it’s not just the use of music in Gloria! that is important in relation to The Extravagant Shadows. That music has been described in language before we ever hear it. It’s an example of a seed that he plants. In one of those statements about his grandmother, he describes the music, so when the music comes on later there is a recognition. We have an epiphany that now we are hearing the wedding music. So it’s not just that the music is there, it’s that we know what this music is based on a prior experience we’ve had. We have learned something. The relationship between language and music in Gloria!—very different than Bruce Conner or Lewis Klahr or Bruce Baillie’s powerful usages of music—helped me understand what was possible. Frampton was setting us up for music to mean something within a context that he had already provided for us.

I was completely knocked out by this way of structuring an emotional experience. So I wanted to explore it myself. Long before “Angel of the Morning” comes on, bits of the lyrics are onscreen. You would have to be a Merrilee Rush fan and know that song pretty well to recognize some of the early phrases, but it is certainly my hope that, after the songs have come on and lyrics continue to appear, you make that connection.

You studied acting when you were younger. How has your actor’s training informed your filmmaking?

I sometimes think of myself not as a filmmaker per se, but a performer, and that I use these films as highly elaborate and painstakingly crafted props. Because I believe that when I’m lucky enough to be present and speaking with a film that what I say beforehand and afterwards is part of my work as an artist. Both the work of speaking and the work that occurs onscreen have to do with activating public space and putting into play a range of ideas. I don’t believe that the work that is on screen must stand alone. Nothing stands alone. Everything operates within a context. Some contexts are more familiar than others, but everything has one, and so I am interested in what happens when I plant seeds in an introduction to a piece of work. That’s part of the composition. It was a strategic decision to begin the premiere of The Extravagant Shadows by speaking about Eric Gill, who is never referred to explicitly within the film itself, although if you know the typeface Gill Sans, you see that a lot of the type is set in Gill Sans and a lot is set in Perpetua, and that there are locations in the film that figured into Eric Gill’s life. I hoped that there would be little moments of recognition. That is where the theater background comes in, because it’s a bit of a performance—it’s thought out—it is part of the composition.

The other way in which being on stage for about a decade has affected my filmmaking is that it made possible, right away, a certain comfort level with, and really, an interest in, the performative aspects of being a teacher. I’m proud of the work that I have done in the classroom and I am grateful that my various academic teaching jobs have provided a structure, both temporally and economically, for me to continue my filmmaking practice. I feel I have been successful as a teacher in large measure because of how I am able to combine what I know and what I believe about cinema with what I am able to do in the classroom as a performer. This has in turn now informed my ideas of how to structure a three-hour block of time with the moving image. At Duke I teach a three-and-a-half-hour class twice a week, and each class is its own composition. I write an essay and I speak each word, I memorize 95 percent of it so that I can mostly deliver it as a monologue, and I try to structure the articulation of meaning in the classroom in the same way that I try to in The Extravagant Shadows. These last three years mark the first time in this 16-year period when I have been making films and teaching that the practices have intersected and are traveling alongside each other.

How so?

Largely through thinking about how meaning accrues in the classroom. I got more interested in thinking about those strategies partly based on some film materials I was working with. In 2001 my grad school friend Ken Eisenstein sent me several 3 x 5 instructional pamphlets from the Little Blue Book series (1919-1978)—How to Write Letters for All Occasions, Home Vegetable Gardening, and The Enjoyment of Reading. This Little Blue Book series is kind of astonishing. Over a thousand of these things on nearly every possible topic that you could ever want to know anything about. What You Need to Know About Phrenology. How to Conduct a Love Affair. I was fascinated by these didactic texts. They then became important in several of my films. These were my first works of condensation as a writing process. The film The Enjoyment of Reading (Lost and Found), which begins with five screens of condensed text from the pamphlet The Enjoyment of Reading, is the very first. Do I need an instructional text about these things, and in what ways do these reduce one’s experience of the world?

My theory of pedagogy at this point, having taught for 16 years and watched things work and fail in the classroom, is that it is most interesting to proceed first by producing a kind of confusion for students. My idea is that, in any given class, the first half should be about the production of a confusion that encourages curiosity while destabilizing a student’s comfort level with the material. Everything I do should raise questions. “Why is he talking about that? How is that relevant to film? He’s talking about music, he’s talking about poetry, he’s talking about opera, he’s talking about gardening. How does this have anything to do with a film class?” And then the second half of class should exist partially in order to relieve some of that confusion, but in a way that is, again, like planting seeds that are going to blossom into a series of recognitions later. I am not telling them something, they have to make the connections themselves. They have to be present, alert. But then when they do make that recognition, it’s far more powerful than if I had just told them the answer to begin with, because they’re discovering it on their own. So by the end of a class, I hope that 90 percent of the confusion is relieved through a series of revelations, and if it’s really going well, epiphanies, that then transmute that last 10 percent of confusion into mystery. And that mystery is what propels you to the next class, where it changes back into confusion. And so on.

That’s what I’m trying to do each week in the classroom, and increasingly in my filmmaking. Film for Invisible Ink, case no. 323: ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST is a prime example. “What is this? How are these phrases related to anything?” But I hope that by the end, some sort of transmutation has taken place, and that these things that were simply Western Union telegraphic code phrases now take on new meanings in the context of a series of wedding vows. The Extravagant Shadows is the fullest exploration of this way of working, and the deepest I’ve gone into planning nested stories, setting things up that pay off later, while being at peace with the risk of confusing viewers for 15 or 20 minutes so that an hour and a half down the line it becomes clear from context why that material was there.

Who are the human figures in the film?

Well, visually, there’s my reflection in the window and in the paint, with my hand blocking light, or my body blocking sunlight. It’s one of the relatively few times that a human body has appeared in my cinema. I didn’t initially decide to present myself. I saw that I was reflected in the glass, and had to consider whether to eliminate my image. And I decided that it was appropriate to see me. Since you were already going to see my hand, it’s not off the table to see the reflection of my whole body.

The other human figures in the film are people that I’ve encountered in books and appear in the movie represented by language. Some are characters—or composites of characters—from stories by James and Blanchot. I recognize one of them as being Henry James himself. And I recognize two of them as being Erin and myself. And I think that at this early stage of getting to know this new work that’s all I’ll say about them.

What is your interest in ghost stories?